The Brazilian doctor who connected Zika to birth defects

- Published

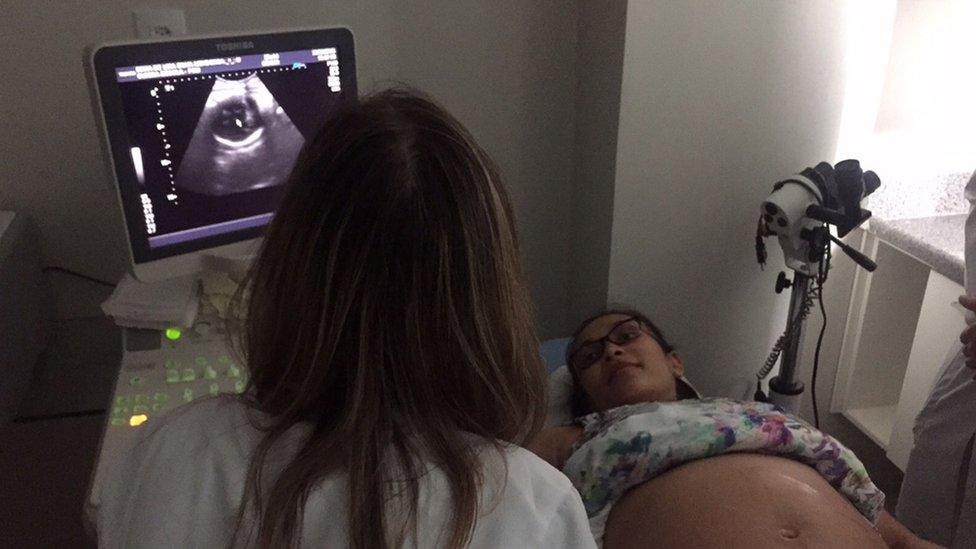

Edna Mendonca had the Zika virus when she was two months pregnant

Friday has become the day of the week Dr Adriana Melo dreads most.

That is because Friday is the day when she performs ultrasound scans of women who were infected with the Zika virus during their pregnancy.

An obstetrician who specialises in foetal medicine, Dr Melo was the first in Brazil to find a connection between the virus and microcephaly, a condition where babies are born with abnormally small heads.

The link between Zika and microcephaly has not yet been confirmed, but the World Health Organisation says it is "strongly suspected".

'Turning their world upside down'

Dr Melo found the Zika virus in the amniotic fluid of two of her pregnant patients in the city of Campina Grande, in the north-eastern state of Paraiba.

Their babies had malformations unlike any she had ever seen in her 17 years of examining foetuses' brains.

Since then, she has had to tell more than 20 mothers that their baby has some kind of neurological malformation because of the virus.

"It's not easy. It's like I'm turning their world upside down," she says.

She says she always takes a short break to take a deep breath in the silence of the dark ultrasound room after the patients walk out.

The majority of the pregnant women who contracted Zika and which Dr Melo examines will go on to have healthy babies, but on any given Friday there will often be at least one case where she has to be the bearer of bad news.

Host of symptoms

Dr Melo says the babies rarely have microcephaly alone but a whole group of symptoms which tend to occur together.

There have been 641 confirmed cases of microcephaly so far in Brazil

That is why she has been advocating for the range of alterations seen in babies to be called "congenital Zika syndrome".

They include:

Arthrogryposis, a condition in which the muscles and joints have contractures

Calcium deposits in the brain in areas where the brain cells are dead

The absence or underdevelopment of brain structures such as the thalamus or the brain stem

Ventriculomegaly, when the babies are born with dilated ventricles and carry excessive cerebrospinal fluid in their head

Dr Melo shows me the image of a brain scan of one of the most severe cases she has encountered.

Dr Melo has seen mothers whose babies had a whole group of symptoms, not just microcephaly

The baby had hydranencephaly, a condition in which the cranial cavity is filled with fluid. She said that there was "virtually nothing" left of the baby's brain, just fluid.

The baby boy died shortly after he was born.

He is one of the 157 babies with microcephaly and/or other neurological problems to have died in Brazil since the investigations started in October, according to the latest figures by the Ministry of Health.

So far, 745 cases of microcephaly have been confirmed across Brazil and another 4,231 suspected cases are being investigated.

The majority of cases by far, 80% of them, have been recorded here in the northeast of the country.

Congenital infection

In its latest reports, the Ministry of Health has broadened its list of cases to include not just babies with microcephaly but also those with "other alterations of the nervous system, suggestive of congenital infection".

The director of the Disease Surveillance Department at the Ministry of Health, Claudio Maierovitch, explains the move.

"I have no doubt that in the future we will be speaking of a congenital infection syndrome for Zika, in the same way we do with congenital measles syndrome," he says.

Currently, the circumference of a baby's head is measured to establish whether it may have microcephaly.

On Wednesday, the government announced new parameters to identify these cases: a head circumference measuring less than 31.9cm for boys and 31.5cm for girls.

So far all babies with heads measuring less than 32cm were considered at risk.

But Mr Maierovitch says the ministry is no longer taking the size of the baby's head as the only indicator for possible damage caused by Zika.

"Sometimes there are other indicators of brain atrophy, such as excessive fluid or calcifications," he says.

Parents' panic

Dr Adriana Melo says the size of a baby's head alone is not enough to identify potential cases.

Edna Mendonca found out her unborn baby's head was smaller than normal. She will have to have further tests.

She says that excessive fluid in the brain can lead the cranium to expand, for instance, and just measuring the baby's head will not detect such cases.

She also says that setting the 32cm mark has caused "a certain panic" for some parents.

"Some babies have smaller heads and are fine," she explains. "The ideal thing is to always carry out ultrasound scans and look for neurological damage."

Dr Melo is trying to find funds for wider studies including women who had Zika but whose babies were born healthy.

"We still don't know if babies born without microcephaly might develop other sorts of problems, such as hearing loss, convulsions or visual impairment", she says.

"Getting funds for research has always been a challenge in Brazil, but in the north-east - one of Brazil's poorest regions - it is even worse," she says.

It is late on Friday night when Dr Melo finally finds the time to speak to us.

She has just finished her round of ultrasound scans.

Of the 17 pregnant women she has seen, one is carrying a baby which is showing signs of malformation.

For Dr Melo, that is one too many.

"Fridays are the worst days of my life. What motivates me is to stop giving mothers this kind of news."

- Published16 February 2016

- Published31 August 2016

- Published26 January 2016

- Published28 January 2016