Cuba's DIY economy raises hope

- Published

Many see Cuba as on the brink of economic changes that will reshape the island

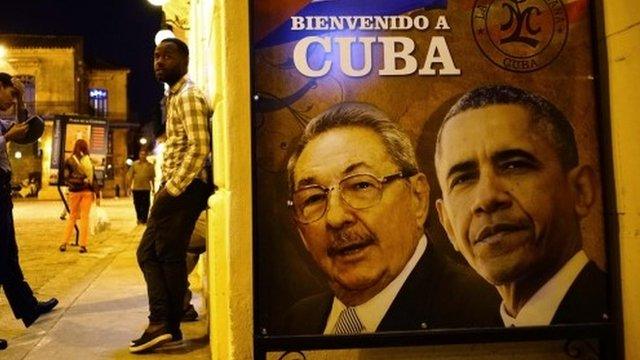

The arrival in Cuba of an American president, after the restoration of diplomatic relations, has raised hopes the island could be on the verge of a new era. And a new emerging class of Cubans is ready to capitalise.

The last time a US president visited the island, he declared Cuba to be "free and prosperous".

Without the use of Air Force One, Calvin Coolidge sailed overnight from Florida, following a journey by steam train from Washington that lasted 32 hours and had no air conditioning.

As President Barack Obama follows in Coolidge's footsteps 88 years later, in considerably superior comfort, he won't be able to make the same bold statement but he hopes his visit can bring that day forward.

His arrival comes at a time when the country could be on the brink of changes that reshape the lives of the 11m islanders and heal one of the world's most fractious relationships.

Such is the excitement among Cubans, especially the youth, he could not have picked a more apt day to arrive than Palm Sunday.

There will not be people waving palms lining the streets but there will be freshly paved tarmac for the president's motorcade, and the monuments on his route have been given a fresh clean and polish.

If only the two nations' differences could be patched up as easily.

Calvin Coolidge (centre) was the last US president to visit Cuba

Economic, diplomatic and political courses are being travelled at varying speeds.

The opening of embassies in Washington and Havana was easy compared to the political challenges facing this one-party state. The slogan "Patria o Muerte", meaning "Country or Die", is still writ large a few yards from the newly restored American embassy, a reminder that the spirit of the revolution is not forgotten.

Perhaps the most interesting changes are taking place in the economic sphere, where a quieter revolution is taking place behind the shutters of Havana homes, on kitchen tables and on laptops put together by spare parts.

This is where a new generation of Cuban entrepreneurs are launching private businesses that are the new economic success story.

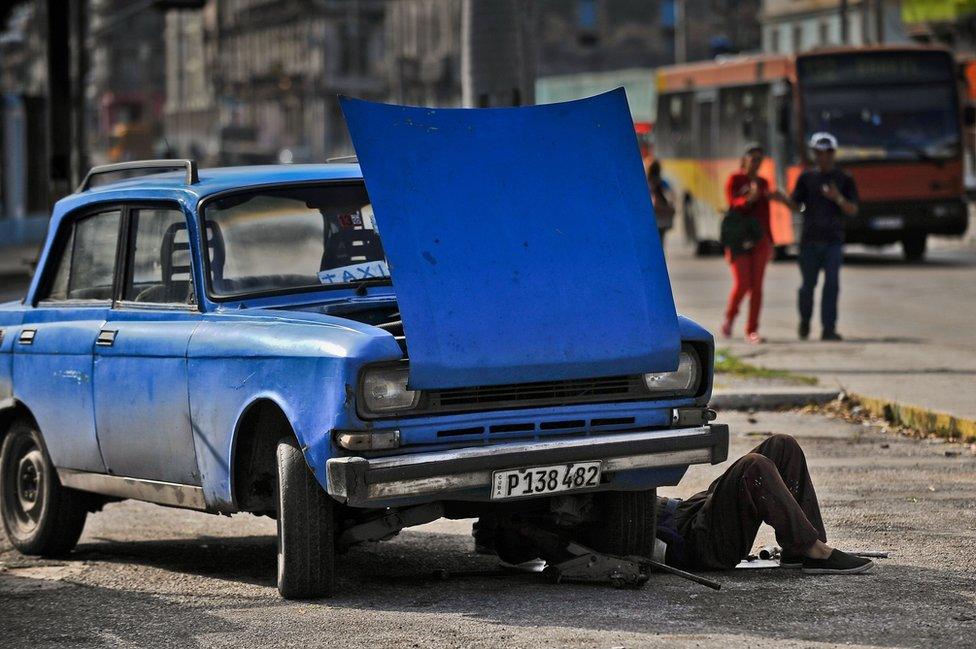

Not all cars in Havana are restored Chevrolets

Six years ago, graduates Eliecer Cabrera and his friend Pablo Rodriguez sat on their sofa, armed only with an idea and a phone directory.

Now they have what has been rated the island's third most popular app, called Conoce Cuba, which tells users on a map what businesses are near them, ranging from cafes to nail salons.

But in a country with neither decent internet nor advertising, it is a triumph of resourcefulness.

How times are changing in Havana

Airbnb cashes in on Cuba tourism rush

Live coverage of Obama's visit to Cuba

They rely on the island's extensive network of mobile phone repair shops to spread the word about their app. Willing customers get the repair shops to download all the app's contents on to their phone for free, so it works offline.

The two entrepreneurs, still in their 20s, make money from the growing number of private businesses that feature on the app. It's a flourishing but up-and-down market.

Two young Cubans have launched a hugely popular app that maps the island's new businesses and places of interest.

"The number of small businesses is increasing by the year but some are going broke too - they are still learning about the market process," says Cabrera.

He is thrilled that Mr Obama is coming to Cuba, in the hope it will hasten an end to the US embargo, which prevents him and his business partner from putting their app on to US websites.

Conoce Cuba is part of a mini-boom in private enterprise. Since becoming president in 2008, Raul Castro has expanded the list of permitted businesses to more than 200 and made getting a licence easier.

Economists estimate between 20-30% of the workforce is now privately employed. In a country where Fidel Castro stood on the steps of Havana University in 1968 and pledged to expel commercial enterprise, that's quite a transformation.

10 (unlikely) professions now legal in Cuba

Benny More was a famous Cuban singer whose life was made into a film

animal groomer

Benny More dance team

button coverer

bed frame repairs

dandy (man dressed in colonial garb)

eyeglass repairs

palm tree trimmer

three-wheeled pedal taxi driver

disposable lighter refill and repairs

operator of children's rides

Barber Josefina Torres was one of the first to join the ranks of the "cuentapropista", or self-employed, 25 years ago when an economic crisis forced Fidel Castro to relax restrictions.

As she gives a tourist a close shave under the watchful eye of several Cuban revolutionaries hanging from the walls of her Havana shop, her face lights up with excitement at the suggestion that President Obama might wander in for a "short back and sides" during his visit.

Barber Josefina Hernandez Torres explains the challenges of running a business in Cuba.

Running a business is much better now than when she started, she says, but there are problems getting supplies. The razor blades and the talcum powder can be hard to find, and friends from Europe and the US donated the red capes she drapes around customers.

The so-called suitcase commerce, when business owners import what they need by hand, is a common feature of Cuba's new private sector.

Niuris Higueras, who runs a restaurant called Atelier, brings spices and herbs from the US and Peru in her luggage.

She creates a new menu every day depending on what she can get her hands on. "I'm working with whatever I find," she says.

Niuris Higueras' menu changes depending on what is available to buy

Since the US and Cuba made a joint announcement in December 2014 that the Cold War deadlock would be broken, her custom has increased by 50%, thanks to the stream of American tourists.

But restaurant owners like Ms Higueras have to go to the same shops as households buying the family groceries, so they sometimes clear the shelves to buy in bulk.

This illustrates how private enterprise in Cuba can be a force for good and bad, says Ted Henken, associate professor of Sociology and Latin America studies at City University of New York.

It delivers wealth, choice, freedom and efficiency, he says. But it also widens the gap between the haves and have-nots.

Which group you fall into usually depends on what connections you have to American dollars, relatives abroad or foreign tourists.

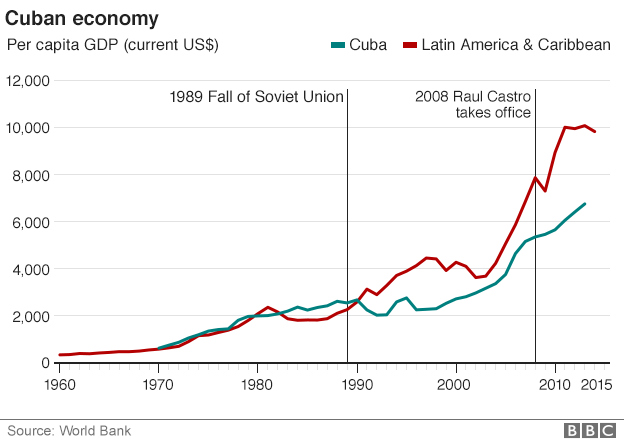

The average Cuban wage is $20 a month, and ever since the fall of the Soviet Union deprived it of an influx of cash, the Cuban economy has been lagging behind the rest of Latin America.

Some Cubans blame the US embargo, which will remain for now because many in Congress believe restoring relations with Cuba does nothing to address its poor human rights record.

But others say the centrally planned economy - what some locals call the "internal blockade" - is as much to blame.

Either way, the future of Cuba seems entwined with the superpower 90 miles from its shore.

And there is no greater symbol of this link than El Capitolio, a neo-classical building in Havana that brings to mind the US Capitol in Washington. Like its nearly-identical twin, it is under repair but Raul Castro has called it a "jewel" that will house the parliament again in the coming months.

A few feet from its manicured lawns, Angel Valencia, 69, is shining shoes. Born into a family of nine children living in one room nearby, he gets a state pension of the equivalent of $8 a month - not enough to buy a round of beers at a nearby cafe.

Angel Valencia has high hopes for President Obama's visit

Having lived in the shadow of El Capitolio for 55 years, its current symbolism is not lost on him. While proud to say he fought in the revolution, he has nothing but praise for President Obama.

"Obama is the first president in 55 years who wanted to help Cuba," he says, with a sparkle in his eyes. "He has many qualities I like. And the relationship will finally heal."

Not all Cubans are so positive about the visit. About 20 minutes away from the old city, rubbish and rubble lie in piles in a neighbourhood that Cubans call a solar, made up of favela-style, mazy alleys and poor housing.

Following a path down an alleyway lined with laundry, there's an opening on the left into a two-room home inhabited by three generations of one family.

The breadwinner Miguel, who did not want to give his real name, says he works two jobs. His income goes entirely on food for him, his three-year-old son and his mother, but it still leaves them hungry.

Mr Obama's visit means nothing to him, he says. "When the changes come, I won't be alive."

The rations system has lasted nearly 60 years

While some of Raul Castro's reforms are making Cubans rich, others are hurting.

The state rations of chicken, rice, eggs, cooking oil and other staples still play a huge part in Cuban daily life. But it is getting smaller and Miguel's monthly ration only lasts about 10 days.

He is often confronted by empty shelves. He points in his ration book to the white spaces that denote the days when there was no bread. In one month, there are 30 spaces in 31 days.

"People here rely on this stuff. As it disappears, so the people are going to disappear as well."

The challenge for Cuba is to ensure the changes that lie ahead benefit the many, not just the few.

- Published20 March 2016

- Published20 March 2016

- Published20 March 2016

- Published20 March 2016

- Published18 March 2016