Brazil crisis: There may be bigger threats than Rousseff's removal

- Published

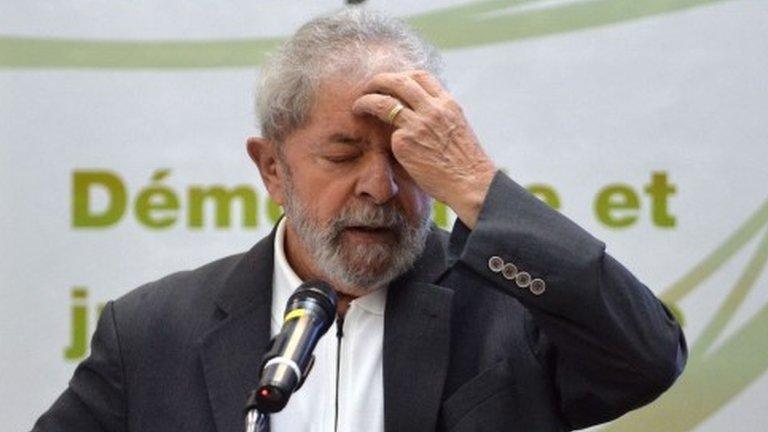

The beleaguered Brazilian president has faced increased calls for her removal

After the most tumultuous week in Brazilian politics since the return of democracy to South America's biggest country, it is impossible to predict with any degree of confidence whether the government of President Dilma Rousseff will survive.

The latest indicator of public opinion, released on Sunday by the respected Datafolha institute, external (in Portuguese), shows that 68% of Brazilians support the impeachment of President Rousseff. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the case against the under fire leader, that figure "feels" about right and Ms Rousseff is on the ropes, in the political equivalent of a bare-knuckle fight for her survival.

Where did it all go wrong?

A decade ago Brazil was the darling of the developing world. A nation whose economy was booming, not just because it was selling raw materials and commodities to China but because it was building its own high-tech industries, training its own engineers and becoming a genuine global "player". Upwardly mobile Brazil soon shoved the UK aside to become the world's sixth largest economy.

Economic and social improvements went hand in hand. An innovative welfare programme called "Bolsa Familia" (Family Allowance), with its emphasis on nutrition and education, helped to lift an estimated 40 million Brazilians out of poverty.

It was no surprise when, in 2006, the popular leftist Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was re-elected as president nor that, four years later, his chosen successor Dilma Rousseff became Brazil's first female leader.

What a difference 10 years make

Roll forward to 2016 and the sheer anger and hatred demonstrated towards Ms Rousseff and Lula in recent weeks as hundreds of thousands of anti-government demonstrators took to the streets of cities across Brazil, showed how bad things have become for the governing Workers' Party.

Many of the old, divisive, traits of Brazilian society have come spilling out as this crisis has escalated.

Brazil's economy faces the worst recession in its modern history, experts say

The almost exclusively white, middle class demonstrators who have been demanding the removal of President Rousseff and the jailing of Lula have a long-held enmity towards the Workers' Party and its left wing economic policies. A small minority of protesters at anti-government events also openly call for a return of military rule.

This is still, despite the gains of recent years, a country with deep divisions between rich and poor, black and white.

At pro-government rallies, the crowds are mixed-race and largely from working-class backgrounds - people who have benefited in recent years from those innovative welfare polices.

They denounce calls for the president's impeachment as nothing more than an attempted coup against a democratically elected government.

Supporters of Ms Rousseff say impeachment calls are an attempt to overthrow a democratically elected government

Fiercely loyal, in particular to Lula, government supporters seem almost blind to mounting evidence of rampant corruption and illegal deal-making during his time in office.

That Car Wash investigation, or Lava Jato, is focused on Brazil's huge state-controlled oil company, Petrobras. It has uncovered billions of dollars of kickbacks, implicating several politicians and some of Brazil's top business leaders.

A politicised probe?

But, by ordering the brief detention and questioning of Lula and by releasing phone taps between him and Ms Rousseff, have the Car Wash investigators overstepped the mark and risked "politicising" their probe?

The common consensus, among independent observers - rather than partisan supporters in this polarised country - is "yes".

Ms Rousseff's rivals have called for her removal on the basis of economic mismanagement

In the coming weeks it is hugely important that the team of largely young investigators, based in the southern city of Curitiba, shake off that perception.

There is evidence to suggest that politicians have tried to influence the investigators' work but, led by judge Sergio Moro, they must show they are actively pursuing corrupt individuals regardless of political allegiance.

The probe has certainly reinforced one perception - that politicians of all colours blatantly milk the system dry, enjoying near total impunity. Meanwhile, ordinary folk are left to deal with the consequences of an economy now deep in recession, rising inflation and a fear of losing many of the gains of recent years.

One recent political debate illustrated this point well as lawmakers in Congress last year approved a modified bill to reduced the age of criminal responsibility.

Residents of many Brazilian cities, including Rio de Janeiro where the geography of the city means that rich and poor live cheek-by-jowl, had become understandably exasperated and scared by rising levels of violent crime.

Many "cariocas" (Rio residents) passionately supported calls for a reduction in the age of criminal liability for certain crimes from 18 to 16. Without really pausing to ask what were the causes of rising crime, city residents argued that long prison sentences and tougher laws were the only way to deal with the gangs of poor black youths who sometimes disrupt the beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema.

Judge Sergio Moro leads the Petrobras corruption probe and has been criticised for his latest moves

Yet the same middle class residents from Rio's "south zone" seem less bothered about the blasé way in which one of their elected representatives in Brazil's Congress carries on regardless, despite numerous allegations of corruption and evidence of secret Swiss banks accounts with more than $5m (£3.5m).

That Congressman, Eduardo Cunha, is the speaker of the lower house in Brasilia. As such he enjoys privileges and legal guarantees that people accused of much lesser crimes could only dream of.

The real threat

More than 150 members of Congress and government officials are currently facing serious charges including bribery, corruption and money laundering. Yet, all of them, including Mr Cunha - who denies the charges against him - can only be tried in Brazil's Supreme Court where the backlog of cases is huge and where they often expire.

The impeachment process against President Rousseff may gather pace. She may decide that she has no other choice but to resign if, by losing the support of coalition parties, she can no longer rule effectively. Or she may try to punch her way out of it.

But perhaps the biggest threat to Brazil's future as a country with genuine freedom of opportunity is if the anti-corruption investigations are quietly watered-down or even suspended.

In such an eventuality the only winners would be the same political and business elites who have ruled this country for decades.

- Published8 April 2018

- Published10 March 2016

- Published4 May 2016

- Published17 March 2016

- Published17 March 2016