Shadow of jailed ex-president cast over Peru polls

- Published

Many Keiko Fujimori opponents believe she is tainted by her father's controversial legacy

Peruvians are accustomed to political scandal, but this year's presidential campaign has raised eyebrows even in a country where trust in politicians is increasingly low.

Just weeks before polling day on 10 April, two leading candidates were barred from the race by Peru's national elections watchdog.

Another candidate, Gregorio Santos, is running for president from a prison cell.

He is currently awaiting trial for alleged criminal conspiracy during his tenure as governor of Peru's Cajamarca region.

Controversial past

But it is the identity of the front-runner that is proving most controversial.

Keiko Fujimori, 40, is the daughter of incarcerated ex-President Alberto Fujimori.

Keiko Fujimori is well ahead in the polls

When she was still in her twenties, she acted as First Lady after her parents divorced.

Opinion polls suggest she has a strong lead and her supporters say she connects with a wide range of Peru's population.

"Over the past four years, she has travelled to 80% of Peru's districts and provinces in order to understand the reality of life in our country," says Luz Salgado, a member of Congress for Ms Fujimori's Fuerza Popular party.

But it is her father's legacy, rather than her current campaign, which makes Keiko Fujimori such a divisive figure and which prompted thousands of people to take to the streets of Lima on Tuesday in protest against her candidacy.

Divisive figure

In 2009, her father Alberto Fujimori was convicted of human rights abuses and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

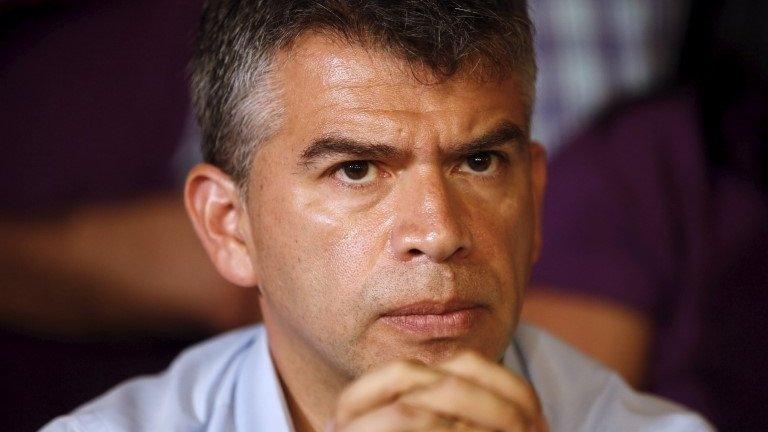

Julio Guzman (centre) is one of the former presidential candidates who has been barred from standing

His government also brought in a controversial sterilisation programme in the 1990s, aimed at controlling Peru's birth rate.

Hundreds of thousands of women and men were sterilised under the policy, with human rights groups saying that as few as 10% might have given their consent.

But many credit Alberto Fujimori with transforming Peru's economic fortunes after his election in 1990.

When he left office in 2000, the country's gross domestic product had doubled to $50bn (£35.5bn), according to figures from the World Bank.

In addition to these economic reforms, Mr Fujimori's government led the fight against rebel groups such as Maoist group Shining Path, which earned him a reputation for being a tough advocate of national security.

Keiko Fujimori's campaign has employed similar tactics, making "seguridad ciudadana" (citizen safety) a key part of her manifesto.

"For a lot of people, Keiko Fujimori represents security. They remember that her father was the one who defeated the Shining Path and terrorism," says Ms Salgado.

Security is also key for 68-year-old taxi driver, Santiago, from the capital, Lima: "I'm not voting for her because of her father but because she is going to improve the security situation across Peru".

Pardon?

For many of the former president's opponents, Keiko Fujimori is just too redolent of her father and his policies.

For a lot of her supporters, Keiko Fujimori represents security

"To us, Keiko Fujimori represents dictatorship, abuse of human rights and theft. If she wins, many people believe she will pardon her father," said Gonzalo Cordova, 35, a member of a local activist group called No a Keiko (No to Keiko).

As campaigning draws to a close, Keiko Fujimori has made a concerted effort to distance herself from her father's legacy.

In the presidential debate one week before election day, she stole the show by signing a "Commitment of Honour" document live on national television.

The document included a promise not to pardon her father if she wins the presidency.

Ms Fujimori's campaign has also been dogged by accusations that she lacks the necessary experience to be president.

Fujimorismo

"Keiko doesn't have any professional experience. She doesn't have an important background. She is surrounded by the same people as her father," said Julio Guzman, the barred former presidential candidate.

As election day approaches, Keiko Fujimori's strong lead in the polls is holding steady at around 36%, according to Lima-based pollsters Datum Internacional.

Her closest rivals, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and left-wing candidate Veronika Mendoza, are locked in a statistical tie at around 16%.

Under Peru's electoral system, there will be a run-off in in June between the top two contenders if no single candidate is able to secure more than 50% of the votes in the first round.

Whatever the outcome of the election, the lack of trust in politics many Peruvians say they feel is unlikely to go away anytime soon.

Mr Guzman thinks the problem runs deeper than just Keiko Fujimori and Fujimorismo, as the political movement her father created is called.

"The establishment runs this country, and they believe that they have the right to do it," he says.

"Peru is a very elitist country. The establishment, which is heavily linked to corruption, is holding our country hostage," he concludes.

- Published9 March 2016

- Published2 December 2015

- Published25 January 2014