Brazil's corruption culture 'can be beaten'

- Published

Corruption allegations have provoked a strong reaction among the Brazilian public

You could easily grow fond of the retail mall in central Brasilia.

Even a visitor who detests shopping can admire the building's quirkiness, a semi-arch that seems almost to fall on to the pavement, embodying the modernist curves which define architecture in Brazil's capital.

This is a city that was constructed virtually from scratch in the 1950s and which is supposed to proclaim the new, progressive side of the country.

Yet the man I had come to meet at the mall had a story as old as his country's creation: "When you bid for a government contract in Brazil, they usually say 'what can you do for us? What can you do to make this contract a win-win for all of us?' They want a percentage of the contract…which means bribes."

His company designed software, successfully by all accounts. Yet the compromises required to win that all-important government business had driven him to despair and he eventually quit the industry altogether.

"I didn't want to play the game, but I knew the game would always be there."

Corruption has been in Brazil for a long time. Some historians trace it back to dodgy dealing during the slave trade, a business often conducted illicitly as well as immorally.

There is even a phrase in the local Portuguese dialect "Jeitinho Brasileiro, external" which loosely translates as "the Brazilian way of doing things".

This can be said admiringly to suggest an ability to solve problems creatively.

Underlying the phrase, however, is a sense that if a problem does have to be solved, it is OK to cut corners and perhaps break the law just to get things done.

And there have been an awful lot of corruption laws broken in Brazil, it seems.

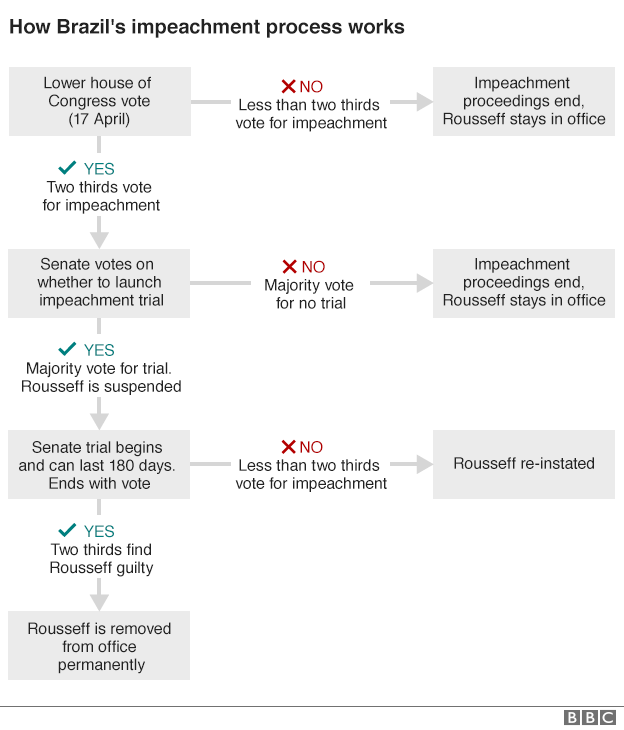

Congress recently voted to proceed with impeachment of the President, Dilma Rousseff, following allegations that members of her ruling Workers' Party had siphoned cash from the state oil company, Petrobas.

However, many of those accusing the president are themselves being investigated for embezzlement, money laundering or other financial skulduggery.

Grounds for optimism

In the midst of such rampant collective larceny, it might seem odd to find optimism among anti-corruption campaigners.

Yet Fabiano Angelico from Transparency International, an independent anti-corruption organisation, says that the sheer number of politicians facing investigation is a sign that the system is finally working.

Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff faces impeachment

"We have built strong institutions," he says. "The federal police, the federal prosecutors, they share information with other countries."

What also might sound surprising is that Congress itself is funding some ground-breaking anti-corruption initiatives - turkeys not only voting for Christmas, you might say, but paying for the festive meal as well.

In a collection of rooms directly under the parliamentary debating chamber, a project called "Hackers Lab" is developing new computer programmes and apps to detect corrupt behaviour.

It makes use of all the published data about politicians and their spending, and then cross-references this with other information, like who owns the companies which the government uses - from major contractors right down to the taxi companies which ferry them around.

Fabiano Angelico believes the system is starting to root out corruption

"The Brazilian government is actually very transparent," says Cristiano Ferri, Hackers Lab's founder and director.

"All the information about how they spend their money is available online."

The problem, Ferri believes, is not one of deeds being hidden. Rather, he says, it is a matter of impunity.

"Everyone in Brazil knows how things are, but we don't have enough punishment."

Politicians protected

The recent scandals have led to a few high-profile business figures receiving long prison sentences.

How corruption works, the Brazilian way

Politicians, however, are harder to prosecute, as membership of Congress confers immunity from normal legal process.

Indeed, cynics have suggested that more than a few have sought political office precisely in order to acquire such protection.

Members of Congress can be charged by Brazil's Supreme Court, though this is seen as a highly-politicised institution.

Many remain unconvinced that a prosecution would be successful, however strong the evidence of malfeasance.

If criminal cases against politicians do go ahead, no-one will be happier perhaps than Luma Poletti, a writer for the website "Congress in Focus".

They were digging up evidence of congressional mischief long before the current run of scandals, proving back in 2009 that members used public funds to buy airline tickets for their families, yet those they exposed held on to power.

"They stay in the Congress for decades - it's frustrating," Luma says, standing outside the Congress building.

She is another who sees signs of progress, the recent scandals, she believes, may prove a catalyst for more investigation and more prosecution.

Yet she fears the Jeitinho Brasileiro attitude is deep-rooted, and will not change any time soon.

"Corruption has been in our society for so many years, people have just gotten used to it."

And with that she walks back into Congress, to carry on digging.

@BBCPaulMoss

- Published24 April 2016

- Published23 April 2016

- Published18 April 2016