Brazil politics: Dilma Rousseff the fighter battles on

- Published

Although I'd met the Brazilian president on a couple of previous occasions, including a very agreeable dinner for foreign correspondents at the Alvorada Palace, her official residence, I'd almost given up hope on a one-to-one interview with Dilma Rousseff.

Two appointments in recent years had been cancelled by her office at the last minute. Given the recent political turmoil in Brazil, an extended interview with the leader of one of the world's biggest democracies was one of those goals, as a reporter based in Brazil, that I'd just about given up on.

So, much to my surprise and thanks to some seriously hard lobbying by colleagues, the news came through this week that we were "on".

I wasn't about to ask "Why now?" especially as this could be the start of her last week as president.

I certainly think there's some truth in the observation that members of the foreign press corps in Brazil have been less hostile in covering President Rousseff's battle against impeachment than some more partisan reporters within Brazil - the openly misogynistic and hostile nature of the debate in the lower house of Congress last month was a revealing window on the brutal nature of politics here.

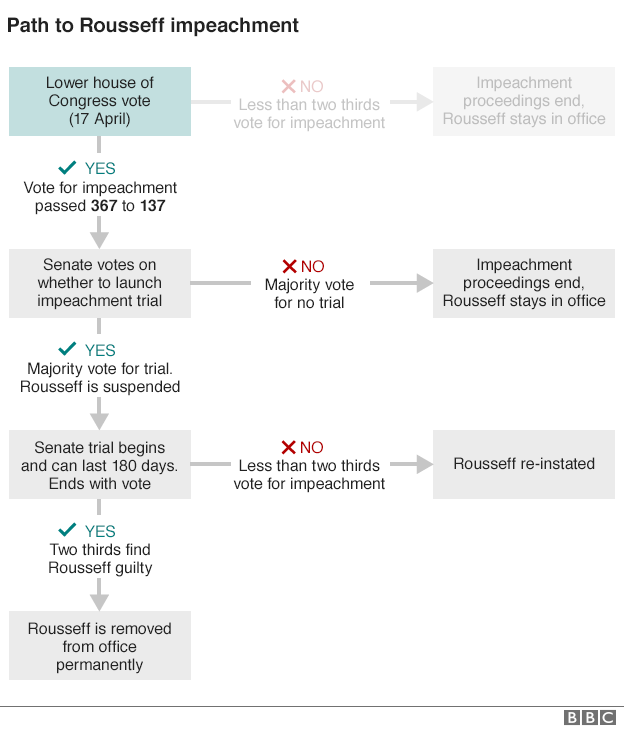

The first thing that struck me was that, given the upheaval of recent weeks, Ms Rousseff appeared relaxed and confident. There seemed to be an acceptance of her immediate fate, that when the Senate probably votes to begin a full impeachment trial, she will be suspended from office for as long as 180 days.

However, along with the acknowledgement that she might have to spend six months in political purdah while her deputy, Michel Temer, occupies her office in the Presidential Palace, there seemed to be a similar air of inevitability that she would return, vindicated, to finish the last two years of her term in office.

Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff tells Wyre Davies the impeachment process is "illegal"

I really can't fathom where that conviction comes from. As Brazil's economy has dived acutely into recession, inflation has risen and people have lost their jobs, hostility to Dilma Rousseff and her government has steadily grown on the streets of Brazil.

Most observers concur that the principal reason for the impeachment process against the president has much more to do with widespread economic and political dissatisfaction than the official charges: that she illegally manipulated ministerial accounts to conceal the size of the deficit.

Nonetheless, I found Ms Rousseff almost immune to the scale of the nationwide discontent. As she's done before, she reminded me of the 54 million voters who'd returned her to office for a second term only two years ago.

She told me: "What's going on is just a disguise for indirect elections, where Congress appoints the president, as opposed to votes from the ballot boxes, cast by the population."

Dilma Rousseff is clearly convinced that a handful of powerful members of Congress and political opponents have taken advantage of the economic crisis to try to force her out.

Her nemesis, the man she believes is almost personally responsible for her downfall, is Eduardo Cunha. He's the powerful, well-connected congressman from Rio de Janeiro who, as president of the lower house, initiated and pushed through the motion of impeachment.

Ms Rousseff told me that she was a victim of Mr Cunha's spite and revenge.

"He's notorious, known to have foreign accounts and is charged with corruption, but it's only because we refused to give him the votes he needed in the congressional ethics committee, that he's done this."

Mr Cunha has denied the allegations.

There was a small crumb of comfort for Ms Rousseff with the news that Mr Cunha, a politician even more unpopular than the president in the country at large, had been suspended from Congress. The Supreme Court ruled that he tried to obstruct a corruption investigation against him and had intimidated other lawmakers.

The irony of these events, which I put to the president, was that had she "played by the rules" and made the kind of deals that her predecessors had always done, she might have avoided the impeachment process altogether.

But Dilma Rousseff, perhaps to her own detriment, says she's not interested in deals, especially the kind of political bartering that amounts to nothing more than corruption.

On a personal note, she has many regrets, among them the sexist nature of the campaign against her and what she calls the "betrayal" by some former colleagues and coalition allies.

The woman who could soon be unceremoniously deposed as Brazil's president is also notably slow to blame herself or to take responsibility for the country's remarkable turnaround in fortunes.

The Olympic flame arrived in Brasilia this week - but will Dilma Rousseff be president during the Games?

When Brazil was awarded the Olympic Games, back in 2009, the economy was booming, millions had been brought out of poverty and had become wage-earning consumers. Almost everyone was happy.

The contrast today could hardly be greater. As Dilma Rousseff welcomed the Olympic Torch to Brasilia this week, she admitted to me it was a bittersweet moment.

It's almost certain now that she'll play no formal role in the Games when they open in Rio on 5 August. Instead, the man she referred to as "the usurper", Michel Temer, is likely to step in. It's clearly something that, as someone who's championed Brazil as the first South American country to host the Olympic Games, really irks Dilma Rousseff.

After all that she's gone through - torture as a political prisoner under the former dictatorship, serious illness and now political humiliation - Dilma Rousseff still calls herself a fighter.

"I'm going nowhere," she replies as I ask her, after our interview finishes, if it will soon be over. But that's a decision that may already be out of Dilma Rousseff's hands.

- Published31 August 2016

- Published8 April 2018

- Published13 April 2016