Brazil dam burst: Six months on, the marks left by sea of sludge

- Published

Julia Carneiro reports

Six months ago, the collapse of a mining dam near the city of Mariana, in the state of Minas Gerais, released a torrent of sludge that killed 19 people, wiped out villages and became the worst environmental disaster in Brazilian history.

The deluge travelled more than 600km (370 miles) before spilling into the Atlantic, leaving a trail of destruction along the Doce River that interrupted water supply in dozens of cities along its course. The iron ore mine was run by Samarco, a joint-venture between mining giants Vale and BHP Billiton.

The causes of the dam failure are still being investigated. Millions of people were affected. Families became homeless, fishermen lost their livelihood, and an indigenous tribe can no longer use the river it depends on. The BBC met some of them.

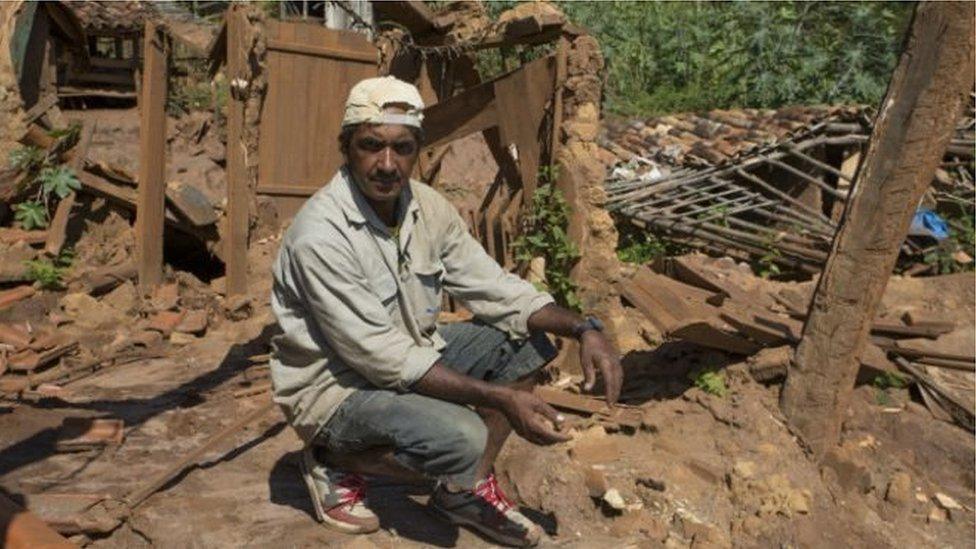

'This is my place', Elias Geraldo de Oliveiras, 43, farmer

Paracatu de Baixo used to be home to 150 families. Now it is a ghost town. The village was devastated by the sea of sludge coming from the tailings dam.

Almost everyone was relocated to the city of Mariana. But Elias Geraldo de Oliveiras insisted on staying. He moved in to his sister's house, one of the few left standing.

"At night it is difficult. It's so dark. It's very lonely. You only hear dogs barking, calling out for people," he says.

"It's as though we lived in one world and now we are in another."

He points out the ruins of his favourite bar, the school, the day-care centre that had just been opened - everything buried in mud, the walls still standing, died in solid ochre.

Paracatu de Baixo was destroyed by sea of sludge

The house he grew up in is destroyed. The mud has dried out at around chest-height, cementing together a bizarre disarray of objects - a record player half dug into the earth, his motorbike, a stove.

He points to the ruins all around and says all the houses were owned by his siblings.

"The community was very unified. Now everyone is scattered apart in Mariana," he regrets. "I couldn't stand to live in the city. This is my place."

'They killed the river spirit', Douglas Krenak, 33, indigenous leader

In the days after the dam break, dozens of cities and communities along the Doce river grew apprehensive, as the stain of mud progressed with the currents.

Douglas Krenak recalls the day the water changed colours by the krenak indigenous village, home to about 400 people in Resplendor, between the states of Minas Gerais and Espirito Santo.

"It was dreadful to see that sea of mud invade the river we have always learned to cherish and protect, with thousands of fish dying and dead animals being carried by the stream. We are still in mourning."

He says the river is fundamentally linked to the tribe's existence. It provides food; it is a setting for games and rituals; it is where they bathe. All that has been suspended for the unforeseeable future.

He says the krenaks call the Doce river "watu", great father or great river.

"And we are known as the 'borum watu', the people of the great river. It is a member of the tribe."

He believes the river will never go back to what it used to be. "They killed its spirit. But my people are considered a minority, so this spiritual connection doesn't matter to them. This will mark us for all our lives."

'Not a land for dreams', Maria do Carmo D'Angelo, 42, farmer

Maria do Carmo D'Angelo lived on the higher area of Paracatu, a rural district of Mariana.

Six months ago, her sister called to warn about the dam break. She rushed to warn the neighbours and pick up her parents who lived further below.

Nobody believed her at first; her elderly parents reluctantly agreed to come with her. When the wave of mud arrived, it was already dark.

"We didn't need to see what was happening. The noise and the smell were so strong, you would feel it kilometres away," she recalls vividly.

Suddenly the mud was at her doorstep. "We looked outside, and my parents' house had disappeared."

The mud spared Ms D'Angelo's house, but swept her yard away.

"I had pigs, chicken, goats, a vegetable garden, all gone. But because my house was standing, I wasn't considered a victim."

She is now battling her rights to get compensation from Samarco and has just started receiving a monthly allowance from the company. It has not replaced what she used to bring from yard to table.

"We always had fruits, vegetables, chicken, eggs."

But she no longer wants to live in the house. "I can't build my dreams under a siren. This wasn't a risk area when my parents bought the land in the past. Samarco made this a risk area. I want them to give me my dignity again, my right to dream - but it has to be in another place."

- Published22 December 2015

- Published23 February 2016

- Published25 November 2015

- Published6 November 2015