Microcephaly in Brazil: The battle to survive the first year

- Published

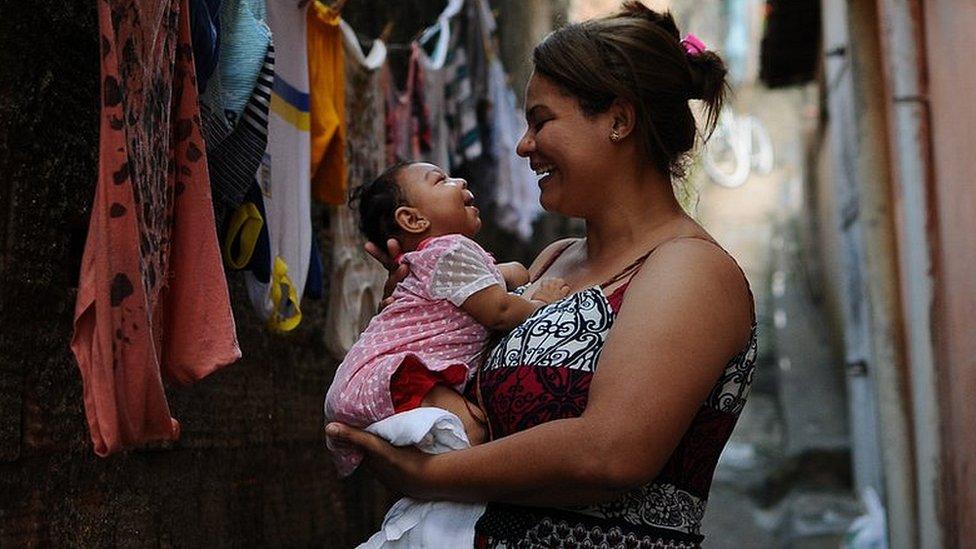

Severina Carla da Silva had to resuscitate her daughter after the baby took milk into her lungs

"I saw my daughter dead in my arms," says Severina Carla da Silva, 32, describing the moment that her six-month-old baby Nivea Heloisa passed out after being breastfed.

"She became purple, stopped breathing and passed out. Then I remembered how to do cardiac massage and did it. That's how she came back to life."

Nivea is one of the 1,581 Brazilian babies diagnosed with microcephaly caused by the Zika virus.

Brazil Zika: The mothers fearing for their babies

Zika fears: The women postponing IVF

And like many of them, she has been having respiratory problems related to the malformation in her brain.

In some cases, those problems have resulted in death.

In the absence of official records for the number of babies who fell ill or died in the past few weeks, mothers' support groups have been trying to keep track.

Risky feed

One support group which communicates via messaging app Whatsapp reported that five or six babies had been taken to hospital within the space of a month.

Six-month-old Nivea suffers from respiratory problems and seizures

Another group said at least 10 babies had been taken to hospital since May.

All of them had similar complaints: difficulty breathing, constant colds or pneumonia, choking and passing out after being fed.

After a week in hospital with her baby, the explanation doctors gave for what happened to Nivea is etched on her mother's brain.

"They [the babies with microcephaly] have a hard time swallowing. When the baby was being breastfed, she took the milk into her lungs", she says.

Specialists who have been following the progress of the babies expected this would happen.

"When you're born, suckling, breathing and swallowing are reflexes. Our brain manages to organise this so we don't breathe and swallow at the same time. But this doesn't happen in the most severe cases of microcephaly," says neurologist Vanessa van der Linden.

"They might be able to suckle properly when they are born, but as they get older, they lose their reflexes and the brain has trouble organising these functions properly. "

Early studies show that about 70% of the Zika-related microcephaly cases in Brazil are severe.

For those babies, the first year of life is the hardest because parents and doctors are still discovering the extent of the babies' limitations, says Dr van der Linden.

During this period, respiratory problems are the biggest threat to their lives.

Deadly seizures

Claudilene Pereira, 31, is from Paraiba, the state with the second most cases of microcephaly in Brazil,

She has also had to take her baby, Matheus, to hospital after a respiratory crisis last month.

Apart from microcephaly, he also had cerebral palsy and epilepsy.

"In the first months he cried 24 hours a day and we didn't understand it. He became red and his head felt really hot. I recorded videos of this on my mobile phone. When I showed it to the neurologist, she told me they were seizures."

Since losing her baby, Claudilene Pereira offers support to other mothers

The difficulties of getting access to the medicines he needed - which are provided by the government but are not always available - show another facet of the families' ordeal.

"Some months he wouldn't be able to take it and his crisis would get worse," she says.

In May, Matheus was taken to hospital. He had serious trouble breathing, but was only admitted to an intensive care unit after three days, following an appeal his mother made on TV.

This story is the same in other states. With a shortage of places in intensive care units, mothers have been turning to the media to put pressure on the health authorities to admit their babies.

Matheus died from a convulsive cardiac arrest during his first night in the ICU, three days before his first birthday.

Extended family

Severina Carla da Silva's husband left her so she relies on neighbours to help care for her children

In the battle for their babies to survive the first year, mothers have been fighting not just the serious consequences of Congenital Zika Syndrome but also a lack of information and a public health system which is itself struggling.

Family and friends are the closest they have to an army to support them.

Ms Silva's husband left her when Nivea - the couple's third child - was born with microcephaly. Her neighbours took his place in caring for the little girl.

"They help me a lot. One of them comes home from work at night the same time as me.

"She goes straight to my house and stays with the baby while I cook dinner and spend time with the boys.

"Later we switch places and have dinner together in my house. That's the only way I can handle it," she says.

Ms Pereira's life remains difficult after her baby's death.

"I still have many debts from the care Matheus needed. But I know I did everything I could for him," she says.

She now dedicates part of her time to offer support and information to other mothers.

"The fact that I lost Matheus does not mean this is not my problem any more. Their children are my children.

"Many mothers have no support. I was lucky [in that I had support], but not everyone is."

- Published2 May 2016

- Published19 March 2016

- Published16 February 2016

- Published3 February 2016