Brazil Zika: The mothers fearing for their babies

- Published

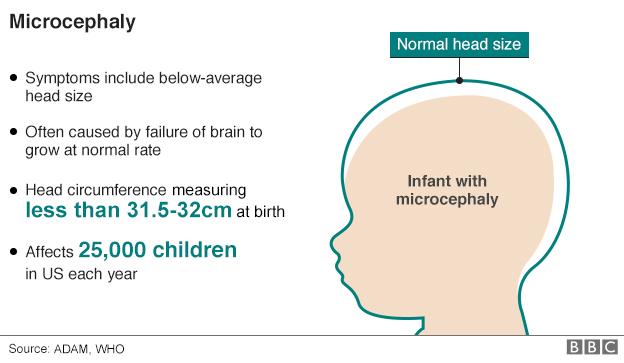

Almost 4,000 cases of microcephaly - abnormally small skulls in babies - have been reported in recent weeks

Mariana Botelho never imagined that being pregnant for the first time would involve the kind of precautions you might need to enter a contaminated area.

Normally, the 33-year-old Brazilian doctor says, "it doesn't matter if it is hot or not, I wear trousers and long sleeve shirts all the time. And I am not using sandals or flip-flops, just trainers or boots."

But for the last three months, Mariana has been taking almost obsessive care to avoid being bitten by Aedes aegypti, a mosquito which transmits the Zika virus.

"If I go to more risky areas, like parks or places with lots of gardens, I also use insect repellent.

"Also my husband and I close our house completely by 5pm, when there are more mosquitoes. And he is now an expert in killing mosquitoes."

When Mariana got pregnant, Brazil was still unaware that the virus, considered then to be the cause of a milder form of Dengue fever, could also cause microcephaly, which prevents a child's brain from fully developing.

"If it was today, I think I might have postponed my plans of having a baby", she says.

Each year approximately 150 babies in Brazilian are born with microcephaly, which can be caused by genetic disorders, drug consumption or congenital infections such as rubella and syphilis.

But from October 2015 to until the second week of January this year, the country has had 3,893 reported cases of the malformation in newborn babies, according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

The surge was first noticed in the northeast of Brazil and was later linked to infection by the Zika virus during pregnancy.

The disease is spread by the same mosquito that transmits Dengue and Chikungunya fever, which Brazil has notoriously failed to tackle over the past decades.

Similarities between the three diseases make it more difficult to diagnose the Zika virus, which entered the country in 2014 and whose possible devastating effects on babies are still new to most of the world.

The majority of the mothers only found out that their babies had the condition after they were born.

What is the Zika virus and why is it spreading across South America?

But as awareness about the disease starts to grow, Brazilian doctors fear an early diagnosis could also increase the number of illegal abortions in the country.

The Brazilian law allows abortions only when the pregnancy is the result of rape and when it endangers the mother's life.

In 2012, the Brazilian Supreme Court ruled that mothers should also be allowed to terminate the pregnancy of anencephalic babies - which are born without most of their brains and typically live hours or days.

'I'll love him the same'

When 17-year-old Valeria Barros heard from the doctor that her newborn baby, Arthur, might have microcephaly, she "felt instantly like crying".

He was born with a head circumference of 33 cm, slightly above the limit used to describe the malformation, but his case was still notified because Valeria showed symptoms of Zika in the beginning of her pregnancy.

There is currently only one type of test available to detect the Zika virus in patients. And it can only find the virus while it is active in the body, during the disease.

The difficulty in finding out if a pregnant woman was infected months ago poses a challenge to scientists trying to establish a definitive link between the virus and the malformation.

Along with 10 other mothers from a small city in the north-eastern state Pernambuco, Valeria travelled almost 400 km (248 mi) to state capital, Recife, in order to find out whether the virus hurt her son.

Mariana Botelho, a doctor, has been taking extra precautions against mosquitos

It can take months for women like her living in rural areas to have confirmation about their newborn's condition.

During that period, both they and their babies are submitted to a number of exams in order to determine whether the child's brain was affected and what exactly might have caused it.

After the first clinical exams, the doctors are optimistic. Even though her baby has a heart condition, there are little signs of other damages possibly caused by the malformation.

However, Valeria is still waiting for the results of another scan which will finally confirm or exclude the possibility.

"The doctor told me he could be paralyzed, blind or deaf. But I'm sure they will confirm he's healthy", she says, in tears.

"Even if he has problems, I'll love him the same. That's what matters."

Dreams

Questions about the consequences of the malformation in their babies are the main source of anxiety to parents who wait for a diagnosis and also for those who have confirmation.

Doctors find it hard to predict accurately the kind of limitations the child will have, since the infection affects different parts of the brain in different ways.

The threat has spread to other Latin American states, like here in Honduras

"The cases vary a lot," says neuropediatrician Durce Gomes de Carvalho, who has been treating such cases in Pernambuco, Brazil's most affected state.

"It could affect their vision, their hearing, their motor skills or their cognitive abilities depending on how hard the infection has hit them."

Once the microcephaly is confirmed, babies have to attend sessions of physiotherapy, speech therapy and others in order to access the damage and stimulate their intellectual and physical development.

"My dream is that he can go to the university. The doctor said he won't be able to do it, but I believe in God", says 20-year-old Erika Roque.

She claims to have had no symptoms of Zika during her pregnancy. About 80% of the cases, according to specialists, occur without symptoms.

Erika Roque son Erick receives physiotherapy

When her son Erick was born, six months ago, his head measured 31 cm.

He suffers frequent seizures and attends physiotherapy sessions in order to loosen his arms and legs, which are stiffer than usual, a condition commonly associate with microcephaly.

Women like Erika have been finding comfort with each other, sharing their stories and exchanging tips on social media pages and WhatsApp groups.

A Facebook page called "I love someone who has microcephaly" has gathered almost 1,500 likes since it was created in the end of November.

"In the beginning it was really hard. But now, seeing other families in the same situation, I feel better informed", says Erika.

- Published31 August 2016

- Published21 January 2016