Argentina worker-controlled companies feel the pinch

- Published

Natalia Sosa says she enjoys working in a worker-controlled factory

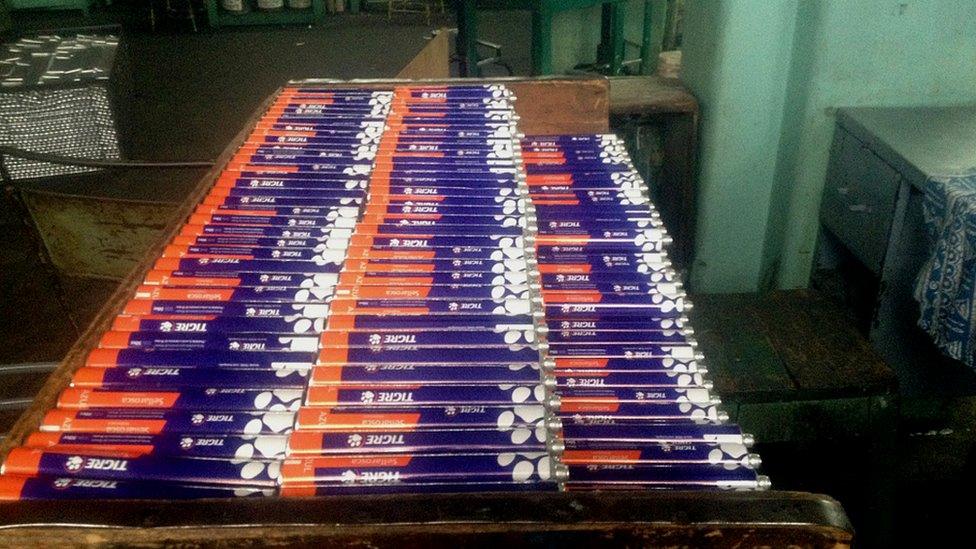

Natalia Sosa works in a factory putting the lids on toothpaste tubes.

But unlike most people who work in factories, she has no boss. The workers here took over the factory when it went bankrupt in 1998.

All the managers or "co-ordinators" are elected by assemblies of employees.

"For me it's an enormous change from working in a factory under a boss, working co-operatively," she says.

"Each of us knows what we have to do. No one tells you what you have to do."

'An education'

This metal and plastics packaging factory in Buenos Aires is one of 367 employee-run workplaces in Argentina.

Since the deep recession of the late 1990s Argentine workers have taken over not just factories but hotels, offices and even clinics and schools.

These "recovered" workplaces employ 15,948 people, according to a study by the University of Buenos Aires.

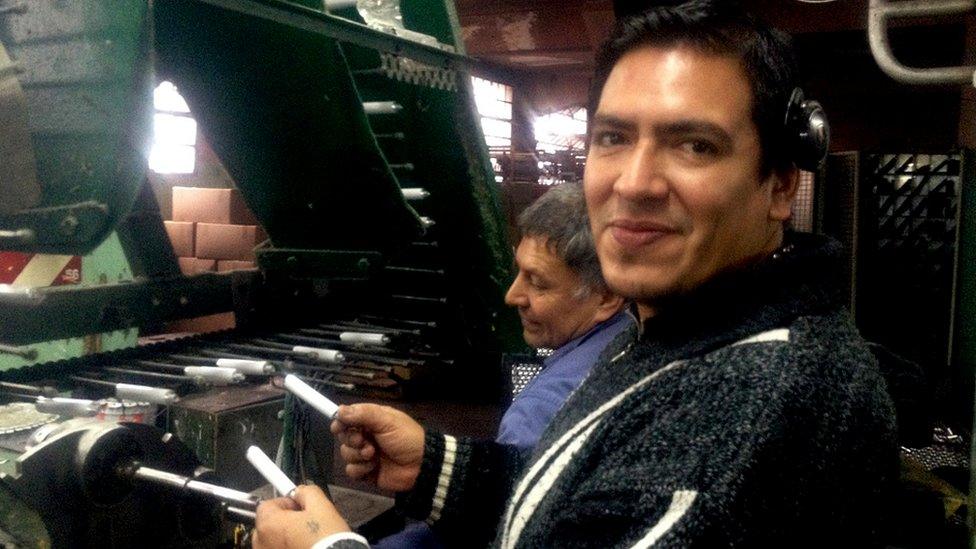

Victor Rodriguez has worked at the packaging factory since 2001, operating a machine that paints the toothpaste tubes.

Victor Rodriguez says working in the factory makes him think about his fellow workers

"It's work and at the same time an education and a commitment to those around you. You don't just think about yourself, but about everyone," he says.

Under the previous left-wing governments of Nestor Kirchner and Cristina Fernandez some of the co-operatives had legal status and received loans.

But many workers at the factory are worried about how they will fare under new conservative president Mauricio Macri, who took office in December 2015.

New approach

President Macri has a more free-market approach, aimed at reviving economic growth and stimulating investment.

President Mauricio Macri has introduced measures to combat inflation and revive the economy

His government has removed price controls, leading to a sharp rise in electricity and gas prices.

It has also reduced tariff barriers so companies now have to compete with cheap imports.

Higher prices also mean that people are spending less and it is harder for Argentine businesses to sell their products.

Eduardo Murua was elected by the workers in the factory to be production manager. He is also a leader of the recovered factory movement.

The worker-controlled factory manufactures tubes for toothpaste

"The problem since Macri took power is the economic plan that he has launched is a savage adjustment which has hit the working class and the Argentine people," he says.

"The impact on recovered companies is particularly great.

"We have also noticed a more repressive attitude towards the workers when they occupy factories."

Changed political climate

Since President Macri took office, six recovered companies have gone bankrupt, according to Andres Ruggeri from the University of Buenos Aires.

He says co-operatives are not just facing an economic squeeze, but a more politically hostile government.

"There has been a series of eviction orders from some judges.

"These are not government orders, but there is a change in the political climate and many cases that were held up in the courts are now being advanced rapidly," he says.

According to Mr Ruggeri, expropriation laws that help recovered companies are being vetoed by the governor of Buenos Aires, who is from the same party as President Macri.

He also says that government programmes that financed worker-controlled companies have ended.

Pro-government congressman Nicolas Massot argues that the government's economic measures are necessary to create a stronger economy and more jobs in the future.

Nicolas Massot says subsidies have to go

"We'll never reduce inflation if we don't eliminate subsidies.

"We know the economic transition is not easy but there is no other way of solving Argentina's economic problems," he says.

Mr Massot says that Argentina's poorest people and some companies are receiving state support to help them during the adjustment period.

He predicts that by 2017 the economy will see stronger growth, slower inflation and rising investment.

'Things will get better'

Julio Marinero has worked in the factory for 28 years.

Julio Marinero thinks President Macri is steering the economy in the right direction

He agrees that President Macri's policies will improve the economy in the longer term.

"The guy's been given a bankrupt country and he is trying to turn it around.

"I'm not political or anything but I think he's doing well. It's not going to happen overnight, but things will get better," he argues.

But workers' production manager Eduardo Murua warns that it will be a struggle for many co-operatives to keep going.

"If you're asking about our factory, I am sure we will survive. We are ready to fight, ready to organise ourselves better, ready to sacrifice a bit more and keep it going, but I think the majority of the recovered companies are going to have a problem.

"The situation is very, very, very difficult."

- Published10 December 2015

- Published20 November 2015