What will be the legacy of the Olympic Games in Rio?

- Published

Preparations for the Games continued until the last minute

Preparations for the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro have been full of controversies and hurdles along the way.

A severe recession in Brazil, a nationwide Zika outbreak and the governor of Rio declaring a state of financial emergency added strain to the difficult task of building venues and infrastructure.

When Rio were awarded the Games back in 2009, the city's 6.3 million people were promised Rio 2016 would leave a lasting legacy of improvements.

Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes has staunchly defended the promises made at the time, saying that Rio is a better place for all the investment poured into it.

"Don't compare Rio to Tokyo or Chicago. Compare Rio to itself," he said referring to Rio's challenging mix of inequality, violence, natural beauty and diverse geography which has proved testing for the authorities.

Below we look at some of the key promises made and ask to what extent they have been met.

Security

Rio's security situation deteriorated very quickly over the past few weeks as the Rio state government, which runs the police, declared a state of calamity over its finances.

Some officers were not paid on time and staged protests at the city's international airport, holding up placards in the arrival lounge bearing the ominous warning: "Welcome to Hell".

In the run-up to the Olympic Games, a few high profile cases of extreme violence further rocked the city.

In June, a doctor was shot to death by muggers in her car in a highway that runs across the city, coming from the international airport that will be used by tourists and teams.

In the space of just six months, 60 members of the security forces have been shot dead.

Violence seeps back into Rio's favelas

The authorities have so far focussed on putting in place temporary measure to ensure security during the Games, such as drafting in extra security forces, but have so far made few permanent changes likely to outlast the Olympics.

Brazil's justice minister has said that the main legacy in terms of security will be the "close co-operation" between federal, state and city agents.

But critics say once the extra personnel leaves the city, Rio will again be faced with rampant violence which saw 1,715 murdered in Rio in the first four months of 2016.

Transport

Transport will arguably be one of the two biggest legacies left by the Olympics in Rio, the other being tourism.

Rio is a very challenging city for urban commuters.

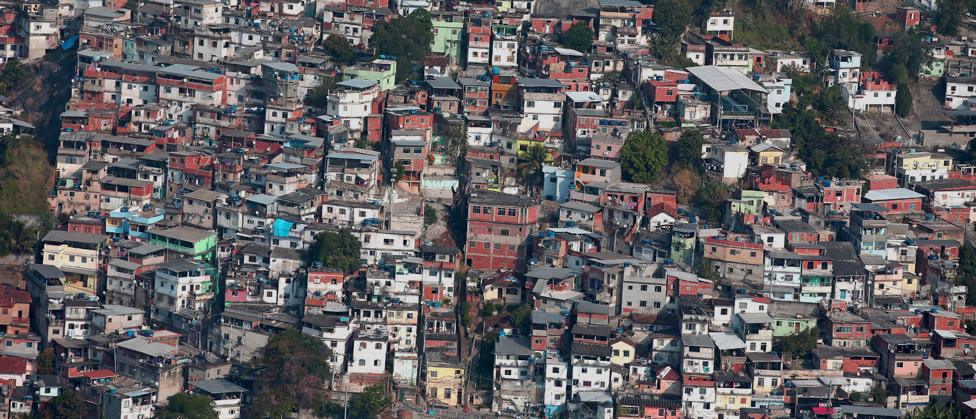

The west side, where most of the Olympic venues are located, is separated from the south and north by long distances and hills where favelas, or shanty towns, are located.

A range of new transport options has been built for the Games.

A new underground line and a new elevated highway connecting the rich neighbourhoods of Ipanema and Barra da Tijuca should reduce costs and travel time for commuters.

Rio's suburbs and poorer north are now better integrated with the west through a new system of bus rapid transit.

And downtown tourist areas now have a new light rail system connecting them to the local airport.

But critics argue that too much has been invested in improving connections with the well-off area of Barra da Tijuca whereas the rest of the city continues to face massive traffic congestion and poor public transport.

Some projects, like the underground, will operate during the Olympics but will shut down immediately after the Games in order for construction, which did not finish in time, to be completed.

Housing

Housing has been another controversial issue with rich areas receiving massive investment and poorer neighbourhoods seeing virtually none.

Rio has one of the worst housing problems in Brazil, second only to Sao Paulo's.

One report suggests that the city would need to build more than 220,000 new homes to accommodate its population adequately.

While London used the impetus of the 2012 Games to provide affordable housing in a regenerated part of town, Rio's approach has been to build the athletes' village in the upscale Barra da Tijuca neighbourhood.

After the Games, the 3,604 flats in the village will be put on the market but because of their cost, they are expected to be snapped up mainly by families of the upper middle class.

Poorer families living in Rio's favelas, which make up a fifth of the city's population, are unlikely to see much benefit from the Games.

A government housing initiative called Morar Carioca was launched shortly after Rio won the Olympic bid and promised to improve all of Rio's favelas in a decade.

But the programme was gradually abandoned and only two out of 40 projects are currently being carried out.

Tourism

Rio already has world-renowned tourist sites such as Sugar Loaf Mountain, Copacabana beach and the Christ the Redeemer statue.

The authorities and the private sector have invested heavily in creating a new tourist hub downtown called Porto Maravilha, external, located where Rio's decrepit port once stood.

A new art museum and the Museum of Tomorrow, external are the main features on the shores of Guanabara Bay, all easily accessible via a new light railway system.

Brazil expects to welcome up to 500,000 tourists during the Games which the authorities hope will spend $1.7bn (£1.3bn) in the country.

Rio authorities have cited the Olympics in Barcelona in 1992 and London in 2012 as events that continued to spark visitors' interest even after the Games but there is little data on the direct effects of hosting the Olympics on tourist numbers.

Sport

In an attempt to increase Brazil's medal score at international sporting events, the Brazilian government has created a national network for training its athletes.

Brazil is far from a sports powerhouse despite the large number of athletes it traditionally sends to the Olympics.

Its best results in Olympic history were achieved in Athens in 2004, when the country won five gold medals and was number 16 in the medals table.

After Rio 2016, two large sports complexes - in Barra and Deodoro neighbourhoods - will be kept as part of the training network.

Rio has also gained a new drug-testing laboratory up to the latest international standards.

Environment

Last year, hundreds of dead fish surfaced in Rio de Janeiro's Rodrigo de Freitas lagoon, killed by pollutants in the water.

Rio authorities promised that one of the lasting legacies of the Games would be the clean-up of the lagoon and Guanabara Bay, where the sailing events will be held.

But that promise has not been kept.

As with other such pledges made about security and transport improvements, the authorities have abandoned the idea of finding solutions that would benefit the whole of the city and concentrated their efforts on cleaning up the areas where competitions will be held.

One of the promises was that by August 2016, 80% of the city's sewage would receive treatment. Environmentalists and activists say the real figure is below 60%.

- Published14 June 2016

- Published2 August 2016