The lessons of Colombia's extraordinary peace process

- Published

Colombia's President Santos (centre) holds a copy of the final text of the peace agreement with the Farc

Decades ago, an IRA bomb in a bin in central London threw to the ground a young Colombian working for the Coffee Federation.

Juan Manuel Santos just happened to be walking by that night. But he then made a point of following Northern Ireland's troubled history of making war, and peace.

"When I saw the picture of the Queen shaking hands with one of the IRA leaders I said, 'My God, this is possible,'" President Santos told me on the eve of signing a historic peace accord with one of his oldest enemies.

In a world dominated by horrific forever wars, Colombia's agreement with the Farc guerrilla movement stands out as an extraordinary moment for this country, and a rare affirmation of the power of peace talks.

"For us it is the most important moment of our generation," said a visibly emotional Colombian negotiator, Sergio Jaramillo Caro, when we meet just before the signing ceremony on the edge of the charming walled city of Cartagena.

Like all guests invited to this occasion, he was wearing white to mark the end of a dark chapter that left more than a quarter of a million dead and tens of thousands kidnapped or who just disappeared.

"What we have seen in Colombia is an example that if you work hard at it, with a lot of international support, you can get something worthwhile," he said, while a Colombian choir rehearsed Beethoven's Ode to Joy on the edge of the picturesque harbour.

Jonathan Powell, the British government's chief negotiator on the IRA deal, has also advised President Santos

And Colombia's own negotiations drew on lessons from places like Northern Ireland and South Africa, whose processes succeeded, and others that failed.

Every conflict is different, but every peace process throws up similar challenges and controversies.

"There's a pattern," says Jonathan Powell, who was chief negotiator on the IRA deal for the British government and became an adviser to President Santos.

"You usually get to an agreement when there is a mutually hurting stalemate, so both sides realise they can't win militarily."

President Santos, a former defence minister, made it clear that his long fight against the Farc - as well as the secret channel he established two decades ago - gave him the gravitas to sit down with his enemy.

"No other Colombian has hit them so hard, so I had the moral authority to negotiate the peace with them," he told me in our interview, a white dove of peace pinned to the lapel of his suit jacket.

The Farc has been fighting the Colombian government since the mid-1960s

One of the toughest challenges is the balance between peace and justice. It bedevils every peace process.

Colombia broke new ground on how to reconcile both.

It is the first peace accord in Latin America that has not ended in an amnesty.

It also brought in to negotiations the victims, who number an astounding eight million, as well as civil society groups.

Colombia's answer to transitional justice includes special tribunals to try Farc members, as well as soldiers and police in Colombian security forces, for alleged war crimes.

There is also a process, inspired by South Africa's Peace and Reconciliation Commission, that allows fighters to admit to their actions, and serve punishments ranging from community service to restrictions on their movements.

I asked President Santos whether he would have wanted a tougher deal.

"I would have liked to see longer jail terms for commanders of the guerrillas," he said.

But he insisted there was no impunity.

"My instruction to negotiators was to go and seek the maximum justice that will allow us peace, and I think we struck a good deal," he said.

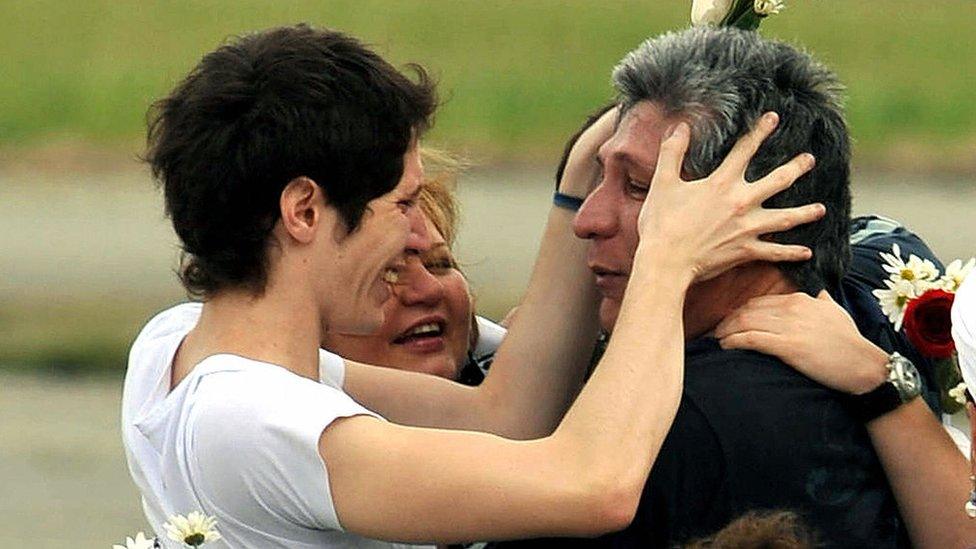

Sigifredo Lopez (right) was held hostage by the Farc from 2002 to 2009

A 52-year war means a generation of pain and distrust.

Some are ready to forgive, even if they cannot forget. But others are not.

In a popular coffee shop in Cartagena, I met former Farc hostage Sigifredo Lopez.

His wife, Patricia, wore a large white badge to show she was voting Yes to support the peace deal in a national plebiscite on 2 October.

"We don't want any more victims, any more violence," Mr Lopez told me emphatically.

His soft eyes still seemed full of sadness.

He was held hostage from 2002 to 2009 with 11 others, and was the only one to come out alive.

"We went to Havana and met our Farc kidnappers," Patricia said.

"They cried when they heard the stories of children whose fathers they massacred, and they accepted their responsibility."

The next morning, at a large loud rally to support the No campaign, I heard the angry voices of those who accuse President Santos of letting the Farc get away with it.

"We want peace, but this accord will not bring peace," said senator Luis Araujo, whose father was kidnapped by the Farc for six years.

"They need to spend more time in jail."

Many Colombians are against the government's peace deal with Farc

"You have to strike a balance," says Mr Powell.

"In Northern Ireland, we let IRA terrorists out of jail after just two years.

"It was a very difficult thing to do.

"But if you go to a terrorist leader and say, 'I want you to sign this agreement to make peace and go to jail for 35 years,' they won't be ready to sign."

If the history of peace deals have any lessons, it is that most fall apart.

Implementation will be tough in a country marred by so much violence.

The Farc, rooted in a Marxist-Leninist peasant revolt, must now move away from its vast network of criminal activities, including the lucrative cocaine trade, in exchange for entering the political process and becoming part of Colombian society.

All the negotiators I spoke to admitted a hard road still lay ahead, but they believed the Farc had changed.

"Any dialogue between human beings changes them," says Norwegian special envoy Dag Nylander, whose country, along with Cuba, served as guarantors of this process.

"What was possible today was not possible four years ago."

"We thought this process was impossible," President Santos said, when I asked him if Colombia offers any hope for other intractable conflicts.

But he also offered a word of caution.

"It would be a deal that will not satisfy everybody but will bring peace - and that's a better deal than continuing the war," he said.

- Published24 November 2016

- Published27 September 2016

- Published24 November 2016