Colombia conflict victim urges 'no' voters to forgive Farc

- Published

Edgar Bermudez was blinded after stepping on a landmine

If anyone has the right to feel angry and not to forgive, it is Edgar Bermudez.

At the height of the conflict between the Colombian government and left-wing Farc guerrillas, Mr Bermudez - then a 26-year-old policeman - was on patrol in a rural area in the south of the country when he stepped on a land mine.

The explosion left him completely blind and with terrible facial injuries.

Eleven years and dozens of medical procedures later, Mr Bermudez is no longer angry with the guerrillas who probably laid the mine that maimed him but he is frustrated with a deeply divided society, which he says has missed a chance to move on and pursue a lasting peace.

"If I and all the other victims of violence can find the strength to forgive and to compromise then those people, sitting behind their desks in the cities, who have not suffered in the same way can surely do the same," Mr Bermudez tells me in his modest Bogota home.

He lives here with his wife and two young daughters, children he has never seen because of his blindness and whom he dotes on.

Scrapping by on a police pension and as a part-time musician, Mr Bermudez worries about what kind of country his girls will grow up in now that a peace deal between the government and the Farc guerrillas hangs in the balance after Colombians' surprise rejection of the deal in a referendum on Sunday.

'Fundamental flaw'

Other Colombians are more optimistic, even interpreting the "no" vote as a positive development.

Former Bogota Mayor Jaime Castro said peace deal was a single party approach and fundamentally flawed

Jaime Castro is a former mayor of Bogota and was a prominent campaigner against accepting the agreement that had taken four years to negotiate.

"The fundamental flaw with President [Juan Manuel] Santos' strategy was that it was a single-party, political approach rather than a national policy," says Mr Castro.

"If what we now end up with is a multi-party solution, acceptable to everyone, it could strengthen the process."

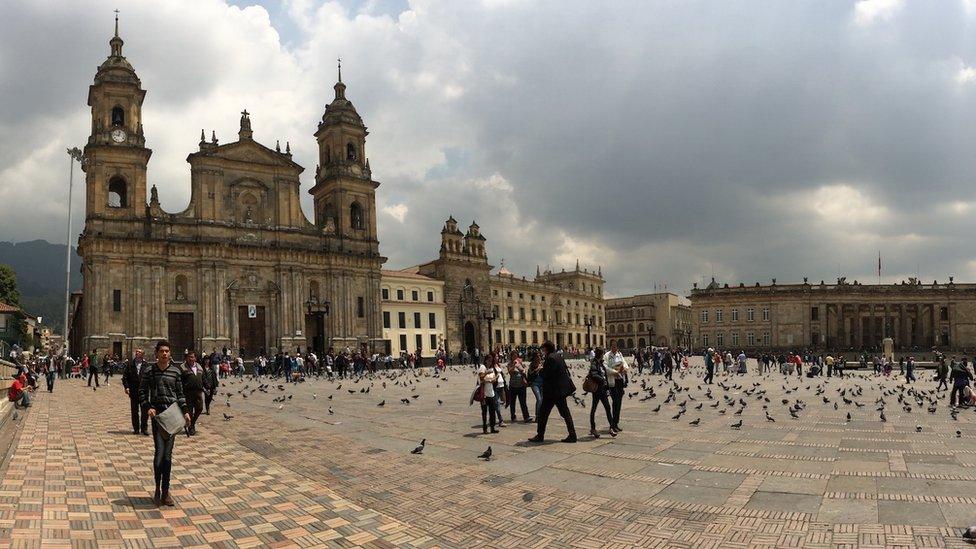

Earlier this week I took a short stroll through La Candelaria, the old colonial quarter of Bogota.

No one wants a return to the violence that ravaged Colombia and its institutions for decades

There is plenty of poverty, misery and crime in Bogota - like any other Latin American metropolis - but the Colombian capital is a much safer and more tranquil place than I remember when I first started reporting from here in the 1990s.

Indeed no one wants a return to the violence that ravaged the country and its institutions for decades.

Juana Acosta was an adviser to the peace talks, which were held in the Cuban capital, Havana.

Adviser Juana Acosta hopes to return to the table for fresh peace talks in Havana

She worked specifically on the issue of justice and political participation.

It is one of the most contentious parts of the existing agreement and Ms Acosta admits that it is probably one of the main reasons why it was narrowly defeated in the referendum.

"Which former guerrillas, who are accused of abuses and violations, will be allowed to take part in the political process and what punishment they must serve for their crimes is one key area that Farc negotiators are going to have to look at again," Ms Acosta tells me.

The adviser, who hopes to be returning to Havana for fresh talks, added: "Colombian society cannot allow again the presence of child soldiers. We cannot allow again atrocities against the civilian population. We are not prepared again to live through such violence so we're going to have to find a way through this and to sign a new peace agreement."

Increasing risk

Those close to the talks, like Ms Acosta, realise that time is now a crucial factor.

The deal was signed before it was put to a popular vote

In recent weeks and months, thousands of Farc guerrilla fighters have been gathering in jungle camps, preparing to hand over their weapons and uniforms.

The plan was for them to rejoin society after demobilising, receiving guaranteed monthly payments from the state and limited immunity from prosecution.

But after the result of the plebiscite, no one is really sure what will happen next.

The longer the hiatus remains, the greater the risk that the Farc members will sink back into the jungle, re-arm, perhaps join other smaller left-wing organisations or criminal gangs making money from the drugs trade.

For now all sides say they are committed to peace but in his latest pronouncement, President Santos warned that a mutually agreed ceasefire between his government and the Farc would expire at the end of October.

While Colombia's ministry of defence has since said that the ceasefire can be extended again beyond that date, Mr Santos' statement was interpreted as a thinly veiled warning to negotiators that they would have only weeks to put their heads together and resubmit a modified agreement.

The president's words also elicited an ominous response from the Farc leadership, with the question; "What happens when the ceasefire expires? Does the fighting start all over again?"

It is a thought most Colombians, especially people like Edgar Bermudez, who have suffered so much already, dare not contemplate.

- Published3 October 2016

- Published24 November 2016

- Published3 October 2016