Good news for Honduras' murder capital?

- Published

The high murder rate means there is a steady demand for coffins in San Pedro Sula

The first person I meet when I land in San Pedro Sula, in north-western Honduras, is local journalist Ingrid Cruz who gives me a tour of her city.

Fewer international journalists come here nowadays, she tells me. There is less interest now that the city is no longer murder capital of the world.

Back in 2011, Honduras had a murder rate of 86.5 per 100,000 people, according to the National University's Violence Observatory.

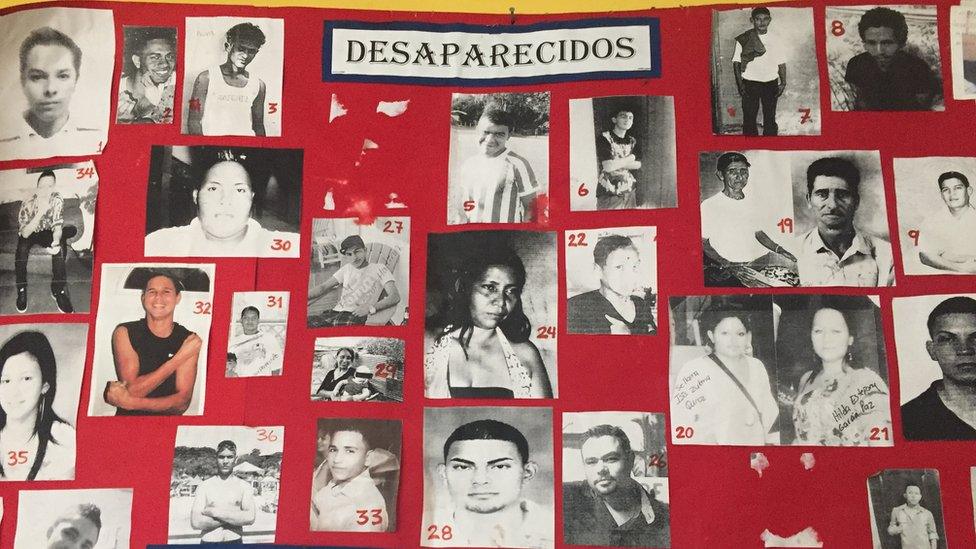

Apart from those whose bodies have been found, there are also many who have disappeared and are feared dead

The country's industrial capital, San Pedro Sula, was the worst-hit.

But by 2015, the national murder rate had decreased to 60 per 100,000. Still not low, but quite a drop.

At the same time, neighbouring El Salvador has been climbing the ladder of violence.

Its national murder rate last year was closer to 100 per 100,000 people. El Salvador is currently the most deadly country outside a war zone.

Spending on security

Ms Cruz points out how much has changed in the past couple of years. Security cameras have been installed on street corners across San Pedro Sula.

More than 2,000 in the past few months.

"The Honduran government has real political will to clean up," she tells me.

"To heal the wounds of the violence, the statistics and deaths through drug trafficking and organised crime."

Ms Cruz says funding from the United States has helped too; programmes that have helped bring the violence down.

Latin America makes up just 8% of the world's population but accounts for nearly a third of all murders.

How did Central America in particular get so bad?

A combination of organised crime and weak institutions has played a huge part, as well as regional instability.

"We've practically got two generations who've grown up in an environment of ideological warfare," says Ramon Renaud, a political analyst who explains that even though Honduras - unlike many of its neighbours - escaped civil war, violence has made its mark.

"The violence in Honduras doesn't have its roots in social issues or a class war. It's more about the bridge that drug-trafficking has formed in Honduras and the Northern Triangle of Guatemala and El Salvador.

"Previous governments have not taken the right decisions to tackle this problem head on. So what happens? It's infiltrated and rooted itself in all the state institutions," Mr Renaud adds.

New technology equals lower crime?

But state institutions are, it seems, trying to change.

I pay a visit to the 911 National Emergency System which has installed all the cameras around the city and has been in operation since late September.

Computers at a new 911 centre help monitor and spot crimes in neighbourhoods

Luis Estrada is the director for San Pedro Sula. He shows me around the fancy new operations room linking up all the emergency and justice systems.

"We're becoming the eyes and the ears of the city and we have to use technology to the benefit of the people," he tells me.

"People complain a lot about violence and that the authorities don't react, so this project makes it easier for us to be able to react and try to combat crime in an organised and directed manner."

But speak to people in poorer neighbourhoods and they don't believe a word of it.

I visited Lopez Arellano, a poor neighbourhood on the outskirts of San Pedro Sula that has heavy gang presence and high levels of violence.

We drove in with our car windows down so people could see our faces.

We stopped at the bus depot which last year was the scene of a shooting that left at least eight people dead when drivers refused to pay what's known as "war tax" - basically extortion.

Eight people died in a shooting incident at this bus terminal in Lopez Arellano last year

There, I met a driver whose brother was killed in that shooting. He did not want to be named.

"It's worse than before," he told me. "They came to get their money and nobody wanted to pay so there was a massacre. I carry on working here but I'm scared. The authorities don't do anything."

And that is part of the problem - impunity.

Military police checkpoints are not an unusual sight in the Lopez Arellano neighbourhood

"This country doesn't really have a functioning justice system so we have a situation where impunity rates are 90% to 95%. Almost nobody gets convicted," says Salil Shetty, the Secretary-General of Amnesty International.

"People are in many cases more scared of the police than they are of the gangs. For ordinary people who are living in poverty and fleeing from violence, it's definitely got worse."

Marta, a mother of five, agrees. Her three sons have been killed in the past 14 years - two of them in gang-related violence.

"The president says violence has fallen X% but that's a lie. Violence continues," she tells me, adding that she fears for her daughters' lives.

On guard

On the other side of town, I visit the city's main public hospital, Mario Catarino Rivas.

Armed soldiers at the door are checking people's ID.

Hospital director Ledy Brizzio explains that the military has been in charge of hospital security for the past two years.

The army guards the city's hospital as well as the morgue

"The conditions, especially in terms of personal security, have improved greatly," she says.

"Before, there was lots of violence and insecurity within the hospital. There were assaults, robberies towards the staff. Now we don't see that anymore because security is under the control of the military."

While authorities are no doubt celebrating that Honduras is no longer in the headlines, the fact that the military is even needed in hospitals is worrying.

The country's president Juan Orlando Hernandez has got tough on organised crime - murder statistics certainly paint Honduras in a better light - but how do you accurately count the incidences of violence such as extortion or rape, in a country where impunity is high and most crimes go unreported?

It seems the reality, for many, is still no better than it was.

- Published20 October 2016

- Published19 November 2014