Colombia connection: The UK's discreet role

- Published

Colombian and British flags on the Mall in London, celebrating a 200-year-old friendship

Tuesday sees the first ever state visit by a Colombian president to the UK. Nobel Peace Prize laureate, President Juan Manuel Santos is visiting for three days as an official guest of Her Majesty The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh.

He will have a working lunch with Prime Minister Theresa May, visit Belfast and attend events at Mansion House, the Natural History Museum and his old university, the LSE. For two nights running, the London Eye will be lit up in Colombia's national colours: red, yellow and blue, a gesture to the 200-year-old friendship between the two countries.

For a country often associated in many people's minds with intractable drugs wars and occasional dubious practices by security forces, this celebration of an alliance may come as a surprise.

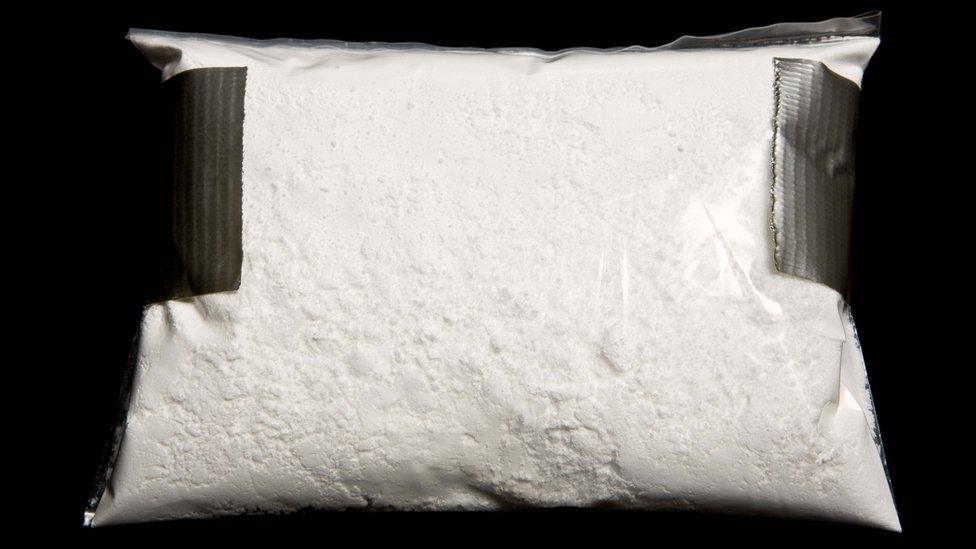

Despite huge improvements in both security and the economy, Colombia is currently ranking neck-and-neck with Peru as the world's biggest producer of cocaine. Latest estimates put production at more than 100,000 hectares, which is nearly double what it was four years ago.

As home to the western hemisphere's longest running guerrilla insurgency - the Farc - hopes had been high that six years of peace talks in Havana would end in a historic deal.

It was duly done, the president shook hands with his longstanding foe, the Farc's Marxist leader, but the country rejected it in a national ballot by the slimmest of margins. Although the ceasefire still stands, President Santos has warned that time is running out and that a revised deal needs to be in place by Christmas.

In the mid-1980s, the Special Air Service (SAS) helped set up Colombia's own special forces

Unknown to most people, the UK has been deeply involved in helping successive Colombian governments in several areas. The relationship runs far deeper than just the annual £1bn ($1.22bn) of bilateral trade.

In the mid-1980s, Britain's Special Air Service (SAS) helped set up Colombia's own special forces, seconding advisers to the country who worked closely with the Colombians, often in remote jungle outposts, training them in patrolling, ambush, counter-ambush and surveillance.

The US Army's Green Berets then took over this role and continue to mentor Colombian special forces today.

In counter-narcotics, the UK has long sought to tackle the problem upstream, before Colombian coke can reach these shores. The Serious Organised Crime Agency (SOCA), as the predecessors to the National Crime Agency (NCA), worked closely with their Colombian counterparts, seconding armed agents to the capital, Bogota, Medellin and other cities.

Today the NCA says it "works with a number of Colombian departments, including the national police and the office of the attorney general… to reduce the threat to the UK from the cocaine trade as well as money laundering and other organised crime".

Peace and reconciliation

And then there is the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), better known as MI6.

Although now playing a somewhat reduced role in Colombian counter-narcotics, Britain's overseas intelligence agency was heavily involved in setting up so-called "vetted units" - polygraphed and trusted Colombian intelligence agents who often took incredible risks to infiltrate the drug cartels, leading to arrests and convictions.

Stormont. Colombia has taken peace and reconciliation advice from a number of Northern Irish figures

MI6 also helped Colombia set up electronic eavesdropping centres, recording incriminating conversations and deals which, again, often resulted in criminal convictions.

Perhaps most surprising of all is the Northern Ireland connection. Colombia has taken peace and reconciliation advice from a number of Northern Irish figures over the years.

Jonathan Powell, who was chief-of-staff to Tony Blair from 1997-2007 and instrumental in securing peace for Northern Ireland, has spent the past five years working with the Colombian government, through his charity Inter Mediate. Ahead of the national referendum on the peace deal, he went to Cartagena to share in the triumph of the accord reached in Havana, only to describe "feeling sick to the stomach" when the people rejected it - by just 60,000 out of 13m votes.

President Santos has not given up yet on convincing the country to accept a modified deal. For him, the lessons of Northern Ireland and reconciliation are incredibly important.

On Thursday he will visit Belfast to meet some of those involved in Northern Ireland's peace process. With a historic peace deal in his own country still hanging perilously in the balance, he will be looking for all the encouragement he can get.

- Published28 October 2016

- Published23 October 2016

- Published4 February 2016