'They will probably die here': Antigua's psychiatric patients' grim future

- Published

Stigma surrounding mental health issues in Antigua runs deep

At suppertime, the angry rebukes for sluggish behaviour appear more suited to a hostel for reprobate teens than a hospital with mental wellbeing at its core.

A glance at the evening's meagre offerings of white bread and saltfish, dished out by a frazzled-looking nurse, suggests one reason for patients' reluctance.

The woebegone state of Antigua and Barbuda's psychiatric hospital, a conglomeration of rickety buildings on the capital city's fringes, is well documented; the reality is jarring.

But the challenges go way beyond inadequate nutrition, beleaguered staff and crumbling infrastructure at this decades-old institution referred to in hushed tones by much of the islands' population.

"It was enough of a feat to get the place an official name," remarks the country's principal psychiatrist Dr James King under whose care every one of Clarevue hospital's 130 patients falls.

"It always used to be called the 'crazy house'."

Stigma runs deep

Stigma surrounding mental health in the Eastern Caribbean nation, like many of its regional counterparts, runs deep.

Read more:

Patients can languish for decades among Clarevue's confines, where they sleep in sparse dormitories, several behind steel barred doors, and visitors are as rare as running water.

The sparse dormitory accommodation offers little in the way of decoration

Some of the windows have steel bars across them

Many would be suitable for discharge were it not for lack of family support outside, Dr King believes.

"A large percentage of people don't need to be here," he says. "Can they discharge themselves? To what programme? To who? To get co-operation from family members is tough.

"Some patients have been here since the 1950s, and they will probably die here."

There is little to keep patients occupied except for some donated magazines

The occupational therapy room was funded by private benefactors in 2013

As for the forlorn facilities, a thick pack of printed photographs taken to show to health chiefs reveals cracked walls, dilapidated bathrooms, blocked toilets and broken water pipes.

"The infrastructure is horrendous," Dr King continues. "The toilets don't flush, there's no maintenance. We have written to all Ministers, past and present; we are tired of hearing they are going to fix it."

Matron Althea Blair, who has worked at Clarevue for 14 years and says she has seen little improvement, agrees. "We don't know what else we can do," she says.

Clinical social worker Pauline Christopher believes the sector has been largely ignored by successive governments because "it's an area that doesn't make any money; it just costs money".

Low morale

Staff morale, she says, is at rock bottom.

"They continue to come to work and do their best but there's a risk people will end up leaving and there'll be a brain drain in mental health," Ms Christopher adds.

Clarevue has seen a number of strikes in recent years by workers protesting the lack of running water, filthy conditions and insufficient risk allowance.

Clarevue is located on the fringes of the capital

The Ministry of Health did not provide comment, despite repeated requests, but an upgrade to Clarevue's facilities, including a refurbishment to the male ward and a kitchen expansion, is listed as a priority in the current budget along with a $141,000 (£112,000) repair programme.

Antigua's antiquated mental health legislation, in effect since 1957 and currently being updated, still requires involuntary admissions to come via the magistrates' court.

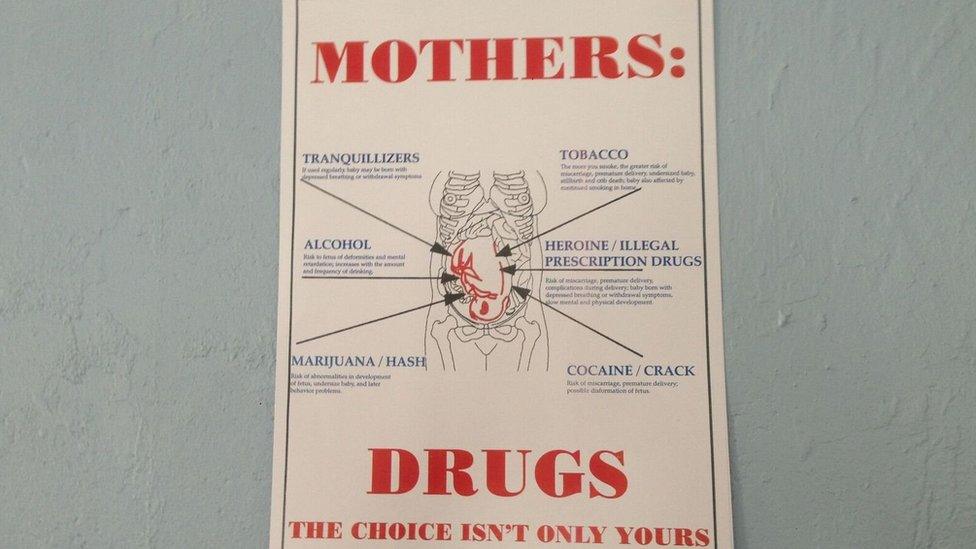

The majority of Clarevue's patients suffer ostensibly from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. But Dr King believes the root cause for many young male patients is the use of hallucinogenic drugs and potent strains of cannabis.

"The symptoms look like bipolar or schizophrenia," he tells the BBC. "The percentage of THC (tetrahydrocannabinol; the principle psychoactive component in cannabis) tends to be stronger these days, we are literally losing a generation of young black men."

A sign warns pregnant patients against drug use

Marijuana's social acceptance makes treatment difficult, says Ms Christopher. "Particularly with those we call the 'frequent fliers'; some people get admitted five or six times a year because of smoking and not complying with treatment."

Another obstacle to recovery, according to Ms Blair, is a lingering cultural belief in witchcraft.

"Some people still believe in witchcraft and take a patient to a pastor instead of a doctor," Ms Blair says. "The pastor tells them to stop taking their meds and pray the crazy away. And then they end up back here."

Given the challenges, it is hard to imagine how patients can possibly recover. Yet some do, Dr King says, thanks to access to modern effective antipsychotic medication and a small core of stressed-out but caring key staff.

Some patients do recover and leave but others have been at Clarevue since the 1950s

Senior house officer Dr Teri-Ann Joseph says increased funding would enable the team to expand services to help eating disorder sufferers, along with children and adolescents. Presently, there are scant resources for youngsters with mental health and behavioural issues.

"What we really need is a new facility. We also want to strengthen the mental health presence in ordinary health care so registered doctors spend time with patients, look for signs, start treatment and work with us. That would help battle stigma," Dr Joseph says, adding: "Sadly, people shy away from things they can't understand."

- Published2 February 2017

- Published12 February 2016