Can Mexico save its journalists?

- Published

More than 100 journalists have been killed in Mexico since 2000, rights groups say

One was killed while resting in a hammock at a carwash. A second was dragged from his car and shot dead near the newspaper he had co-founded. When another was killed in front of her son, the criminals left a note: "For your long tongue".

Journalists are being murdered in Mexico and this is nothing new. This is one of the most dangerous countries for reporters, rights groups say, and more die here than in any other nation at peace.

But even for a place so used to drugs-related violence and organised crime, the recent bloodshed has been shocking.

Seven journalists have been killed in the country so far this year, most shot by gunmen in broad daylight. Yet virtually all cases of attacks on the press end up unsolved and, in many, corrupt officials are suspected of partnering with criminals.

As the killings mount, is there anything that Mexico can do to save its journalists?

'A network of evil'

Miroslava Breach used to say that corrupt politicians were more dangerous than drug traffickers. For almost 30 years, she investigated cases in which authorities and criminals appeared to work hand in hand in her native state of Chihuahua, in northern Mexico.

Last year, Miros, as friends called her, reported, external for the national newspaper La Jornada on the alleged links between organised crime and candidates standing in the local elections in several towns in western Chihuahua - some located on lucrative drug-trafficking routes.

For her enemies, she had crossed a line.

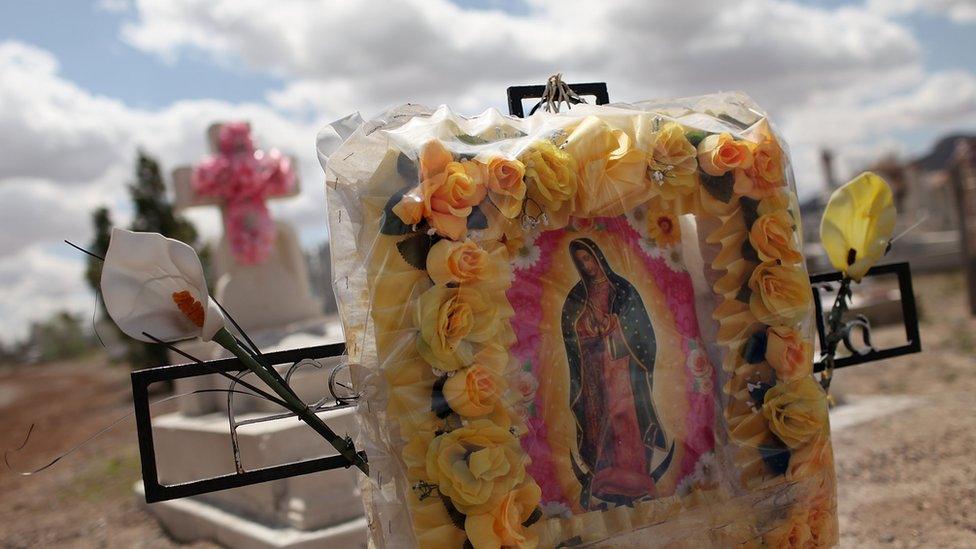

Drug-related violence has claimed the lives of thousands of people in Mexico

"Sister, now I'm really scared," her sister Rosy recalled a tearful Breach saying, as threats had increased and regularly mentioned her children. Breach alerted the authorities but carried on, not knowing what else to do.

"She said that against a network of evil there was nothing that could be done," Rosy said.

Then last March, as Breach left home in the morning to take her 14-year-old son to school, gunmen shot her eight times. They left a note, reportedly carrying the initials of one of the bandits she had denounced and a message: "Por lengua larga," meaning for your long tongue.

"Journalists don't trust authorities"

Since 2000, at least 106 journalists have been killed across Mexico, according to rights group Article 19. Exact numbers are hard to come by as investigations often get nowhere and different studies apply different criteria in counting the dead.

Last year alone, there were 11 deaths, the group said, a record.

Up until now, most of those killed worked for small, poorly resourced local publications. So when Breach, a reporter for a national newspaper, was killed, it resonated throughout the country, her smiling photo becoming one of the many symbols of this tragedy.

For Oscar Murguía, editor of Norte newspaper in the northern city of Ciudad Juárez, which published Breach's column, it was too much. His reaction was to shut the paper, after 27 years. Its last headline was a single sentence: "¡Adiós!".

"It's a tragedy," Mr Murguía told the BBC. "It's an attack on our society, not only on journalists... There's no respect for the work of journalists. I prefer to have a journalist without a job than without life."

Journalists hold placards demanding "Justice": activists say that impunity fuels the violence against the media in Mexico

In 2010, pressure from campaigners led to the creation of a special office of the federal prosecutor for crimes against freedom of expression, known as the Feadle, which investigates attacks on journalists.

But the authorities have often ruled that the victims themselves are not journalists or that the incidents have no connection to their work, according to critics.

Like last month. When the charred remains of Salvador Adame, the head of a TV station in the western state of Michoacán, were found, state prosecutors said that the case had to do with personal disputes, possibly a love affair, angering relatives and campaigners.

The office rejected numerous requests for comment.

Several Mexican cities are among the most violent in world, largely due to the drug war

The deaths continued. Then, in 2012 the federal government set up a specific protection mechanism for journalists and human rights defenders under threat.

More than 600 people have been helped, external by the programme, which can relocate professionals and their families, give them police protection and a panic button, which sends a distress signal to officials via cell phone networks.

Welcomed at first, many now say that very little has really worked.

The flaws were many, a report in 2015, external said. They went from the unreliability of the emergency devices in areas where mobile coverage was poor, to complaints of calls to hotlines going unanswered.

The government disputed this, saying in a statement to the BBC that "achievements" have translated into "tangible benefits" for those assisted.

But last year, for the first time, a reporter under protection was killed - in front of his own house.

'Let them kill us all'

Award-winning journalist Javier Valdez was Breach's colleague at La Jornada, as a correspondent in the western Sinaloa state, home to the powerful cartel once led by Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán.

"Let them kill us all, if that is the death sentence for reporting this hell," was Valdez's reaction to her murder.

Violence in Sinaloa state spiked after the extradition of "El Chapo"

His was another life devoted to exposing the workings of bandits. Three decades of reporting on crime and access to drug lords had made him a star reporter, beloved by colleagues, in Mexico and further afield, who admired his clarity and good humour.

It was a work not without risks.

The offices of Río Doce, the independent weekly newspaper he co-founded in the capital Culiacán, were attacked in 2009 after it published a series on drug trafficking.

"They wanted to scare us, make us afraid so we would stop publishing," Valdez told, external the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in 2011, when he was given an International Press Freedom Award.

Still, he vowed to carry on. "To die," he said, "would be to stop writing."

Javier Valdez - seen here in trademark Panama hat - was threatened for months

Violence in Sinaloa spiked after El Chapo was extradited to the United States, in January. Valdez attributed this to a vacuum of power at the top of the group.

In February, Río Doce published an interview, external with an envoy of "El Licenciado", who was seen as El Chapo's possible successor. Armed men bought every issue, activists said, and Valdez saw it as an attempt to intimidate him. (El Licenciado was arrested in May.)

What came next were months of threats. Then in May, Valdez, wearing his trademark Panama hat, was dragged from his car by criminals at midday, on a busy street near the Río Doce offices. They shot 12 times, killing him on the spot.

No other murdered journalist had as high profile as him. Many saw it as a message: if he can be killed, anyone can.

"Of course we knew the risks," said Ismael Bojorquez, a long-time friend who co-founded Río Doce with Valdez. "[But] every time we felt under threat, we never thought of asking for the protection of the mechanism."

"The [Feadle] doesn't have resources or teams to investigate. Our system of protection of journalists doesn't work... The government's policies to protect us are a failure."

The result is that journalism itself has become a victim. "Investigative journalism in many places in Mexico is just impossible to be exercised," said Carlos Luria, CPJ's senior programme co-ordinator for the Americas.

"There are no guarantees, no condition, no protection, there is an absence of the state. This is decimating journalism in Mexico."

Most of the reporters killed covered crime and corruption for local publications in violent states

In almost all cases, campaigners say, the criminals are never identified, found or tried. "The level of impunity is 99.75%," said Ana Cristina Ruelas, Article 19's director for Mexico and Central America.

Corruption is rife in Mexico, and rogue police and politicians were the suspects in more than half of the incidents against the media in the last six years, she said. And most cases were never looked into.

"The state doesn't investigate itself. There is a direct link between the level of impunity and corruption," Ms Ruelas said. "This impunity allows the aggressors to continue attacking the press in broad daylight."

'The state is killing us'

At the National Palace in May, reporters interrupted President Enrique Peña Nieto's minute of silence in memory of the journalists killed, shouting: "Justice, no more speeches".

Valdez's death added to the pressure on Mr Nieto to address the issue. He said he shared the "indignation" and vowed to "combat the impunity", making promises to boost the protection of journalists and the special prosecutor's office.

Activists say 93% of all homicides in Mexico are unsolved

But many hold little hope for real change.

Blanche Petrich helped found La Jornada in 1984, and knew both Breach ("the number one") and Valdez ("one of a kind"). With two of its main stars gone, the paper is now a newsroom in mourning.

"I don't have any hope," she said. "It's a myth that the cartels are killing the journalists, it's the state. I don't have any trust in Mr Nieto. He's been very indifferent to the problem."

"Nothing works if the assassins are free and those behind the killings are never brought to justice. With this reality, it's very difficult for any journalist to have any trust that those measures are not a simple formality."

"No to silence": journalists have held protests demanding the government to investigate the killings

Distrust grew even further last month, after the New York Times accused the Mexican government of spying on several top journalists, lawyers and human rights defenders by hacking their phones with spyware meant to be used against criminals and terrorists - a claim the Mexican presidency denied.

"It's very hard to connect the words of the presidency with actions because until now we haven't found a clear reflection of these words in actions that provide results," said Ms Ruelas, from Article 19.

Reporters, however, say the latest killings prove that their work is more urgent than ever: "No to silence".

All pictures copyrighted.

- Published23 June 2017

- Published24 October 2019

- Published20 June 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published23 March 2017

- Published4 October 2024