Murdered journalist Javier Valdez on the risks of reporting in Mexico

- Published

Javier Valdez told an interviewer two months ago that he dreamed of another Mexico

Javier Valdez knew he was living on borrowed time.

An award-winning reporter who had fearlessly chronicled Mexico's deadly drug trade, he remarked at his book launch last year that being a journalist "is like being on a blacklist".

The government's promises of protection are next to worthless if the cartels decide they want you dead.

As Valdez put it: "Even though you may have bullet-proofing and bodyguards, [the gangs] will decide what day they are going to kill you."

The 50-year-old was dragged from his car and shot dead on Monday, in Culiacan city, Sinaloa, where he lived and worked.

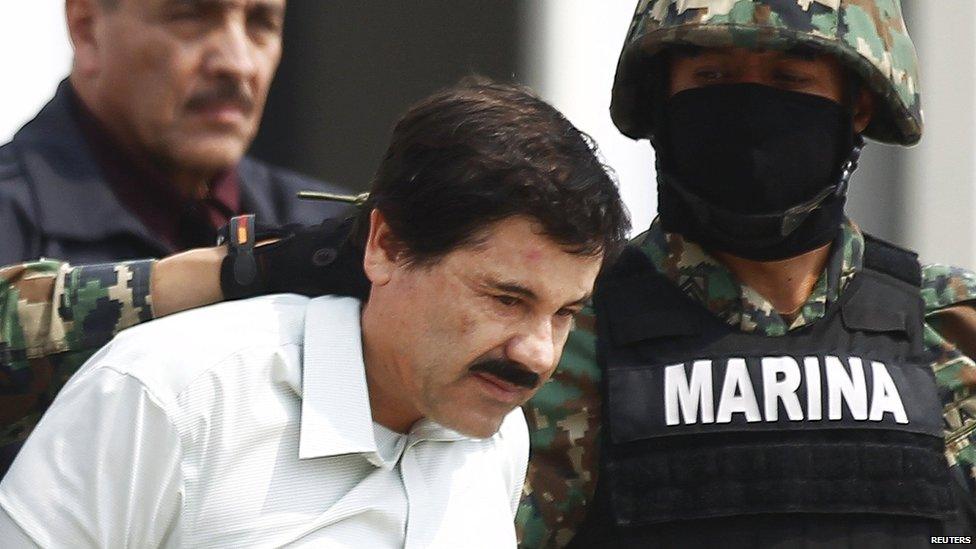

Over a three-decade career, Valdez founded the Ríodoce newspaper in Sinaloa, the north-western state blighted by Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman's powerful drug cartel.

He was also a correspondent for the national newspaper La Jornada, and the author of several books, including Los Morros del Narco [The Children of the Drug Trade], which followed young people through Mexico's bloody underworld.

In public, he often spoke of the risks facing reporters in Mexico, which has one of the world's least free presses.

His words illustrate both the cost of printing the truth, and the bravery of those who continue to do so.

Hand grenades and threat calls

Last month, Valdez told the freedom of expression organisation Index on Censorship, external that a hand grenade had been thrown into Ríodoce's offices in 2009 - but had "only caused material damages".

"I've had phone calls telling me to stop investigating certain murders or drug bosses. I've had to suppress important information because they could have my family killed if I mention it," he said.

"Sources of mine have been killed or disappeared… The government couldn't care less. They do nothing to protect you. There have been many cases and this keeps happening."

Valdez was shot dead in Culiacan, Sinaloa,

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), at least 40 journalists have been murdered in Mexico since 1992.

Fears for family

The journalist's brother Rafael Valdez told Agence France-Presse that he had tried not to expose loved ones to the hazards of his profession.

"He was very reserved when it came to his work," Rafael said. "He never talked about it so as not to drag people into it.

"I asked him several times whether he was afraid. He said yes, he was a human being. So I asked him why he risked his life, and he replied: 'It is something I like doing, and someone has to do it. You have to fight to change things.'"

Sometimes, reporters are forced to flee Mexico under threat of death - knowing they will be murdered if they ever return.

"Now they must be content seeing their homes through the internet. They have been banished from their families for the rest of their lives," Valdez told Revista Desocupado, external [in Spanish].

Murdered friends

In March, Valdez's colleague Miroslava Breach - a crime correspondent for La Jornada - was killed by being shot eight times in front of one of her children.

The gunmen left a note saying: "For being a loudmouth."

Valdez raged against her death on Twitter, external, writing: "Let them kill us all, if that's the death sentence for reporting this hell. No to silence."

Other Mexican journalists killed in 2017 include freelancers Maximino Rodríguez and Cecilio Pineda Birto, CPJ records show., external

Miroslava Breach reported on organised crime and corruption

Narcos in the newsroom

Mexico's violent cartels are well known for using informants. While researching his book Narcoperiodismo [Narco Journalism], Valdez realised that local newspapers were being regularly infiltrated by gang spies.

"Serious journalism with ethics is very important in times of conflict, but unfortunately there are journalists who are involved with narcos," he told Index on Censorship.

"This has made our work much more complicated, and now we have to protect ourselves from politicians, narcos and even other journalists."

In Narco Journalism, he describes how reporters are exiled, murdered, corrupted, terrorised by the cartels, or betrayed by police or politicians in the pay of the gangs.

He told Revista Desocupado: "It is not only about the criminal drugs trade, now they kidnap, extort; they have control of the sale of arms, beer, taxis; they control hospitals, police officers, the army, people in the government and those who finance them. The omnipresent narco is everywhere."

A lonely battle

Valdez felt frustrated and alone in his fight to keep an independent newspaper running.

"I don't see a society that stands by its journalists or protects them," he said. "At Ríodoce we don't have any support from business owners to finance projects. If we went bankrupt and shut down nobody would do anything [to help]. We have no allies."

He feared his newspaper would not outlast this apathy.

"We need more publicity, subscriptions and moral support - but we're on our own. We're not going to survive much longer in these circumstances."

For Valdez, Mexico had become accustomed to death, evil and abuses - a nation resigned to serial murder, because acceptance is easier than fighting.

But as recently as two months ago he was determined to persevere, telling an interviewer:

"Inside me there is a pessimistic bastard, distressed and sometimes sullen, who feels like a somewhat bitter old man with watery eyes, who is bothered by having his solitude spoiled. But he dreams. I have an idea of another country, for my family and other Mexicans, that does not continue to fall into an abyss from which there may be no return."

Mexico's President Enrique Peña Nieto has condemned Valdez's killing as an "outrageous crime", and said his government remained committed to press freedom.

Last week, Mexico appointed a new prosecutor to investigate crimes against freedom of expression - including the murder of journalists.

Sinaloa state attorney general Juan Jose Rios said Valdez's shooting was under investigation.

He promised the authorities would protect Valdez's relatives and colleagues, telling reporters: "Above all else, we are interested in Javier's family."

- Published16 May 2017

- Published15 May 2017

- Published20 January 2017

- Published31 January 2016

- Published13 August 2015

- Published16 May 2014

- Published13 October 2012