Why flying goats in yoga pants could save a Caribbean island

- Published

Some goats are put in shower caps for their helicopter ride to keep them calm

As the tiny, rugged isle of Redonda appears like an eerie moonscape through the rain clouds, it is easy to see why people refer to it simply as "the rock".

Almost devoid of vegetation, this tiny remnant of a prehistoric volcano looks like a hulk of nothingness.

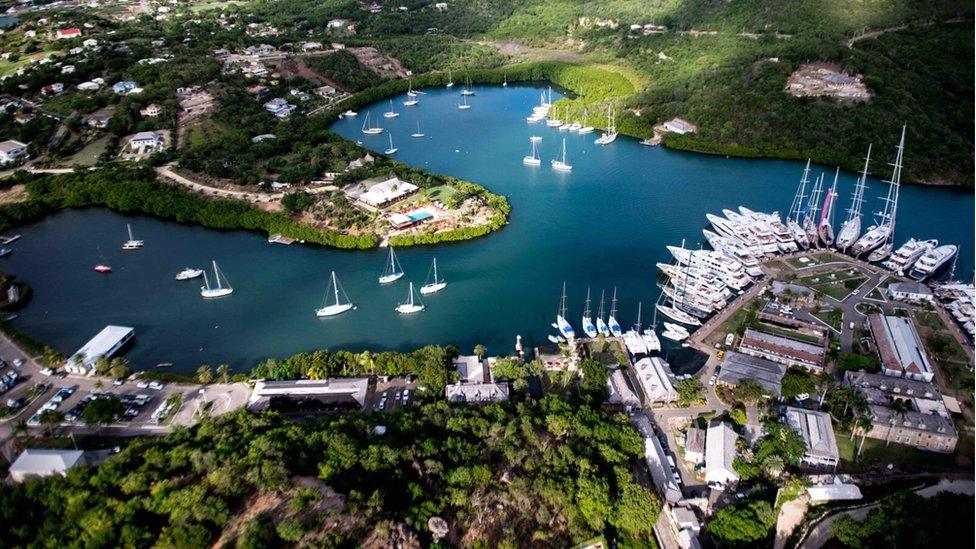

This is Antigua and Barbuda's third island, the one you will not find in tourist brochures. It could not be further from the lush landscapes fringed by white-sand beaches that helped put its sisters on the map.

Redonda, stretching just one mile (1.6km) long, is entirely uninhabited save for a handful of conservationists, who are currently camping here. And some perplexed-looking goats which, until February, had the island to themselves for decades.

It may seem uninspiring at first glance but environmentalists hope to transform its barren terrain into a fertile eco-haven.

Its desolate appearance belies its status as prized seabird habitat, home to rare and unique wildlife found nowhere else on Earth.

Yet these reptiles, tropical birds, frigates and boobies have been in danger of disappearing thanks to two invasive species introduced by early colonists.

Antiguans refer to the country's uninhabited third island of Redonda as "the rock"

The long-horned goats, brought here 300 years ago, have eaten almost all the plants that once carpeted Redonda. Now with barely anything left for them to feed on, many have starved to death, their carcasses littering the land.

Conservationists hope that by re-homing the 75-strong herd on to the main island of Antigua, around 30 miles (50km) away, Redonda will be able to flourish once again.

Several have already been flown out by helicopter. To keep them calm on the 20-minute flight, shower caps or hoods made from yoga pants are put on their heads. Protective material, which actually comes from swimming floats known as noodles, is wrapped around their horns so they do not injure each other.

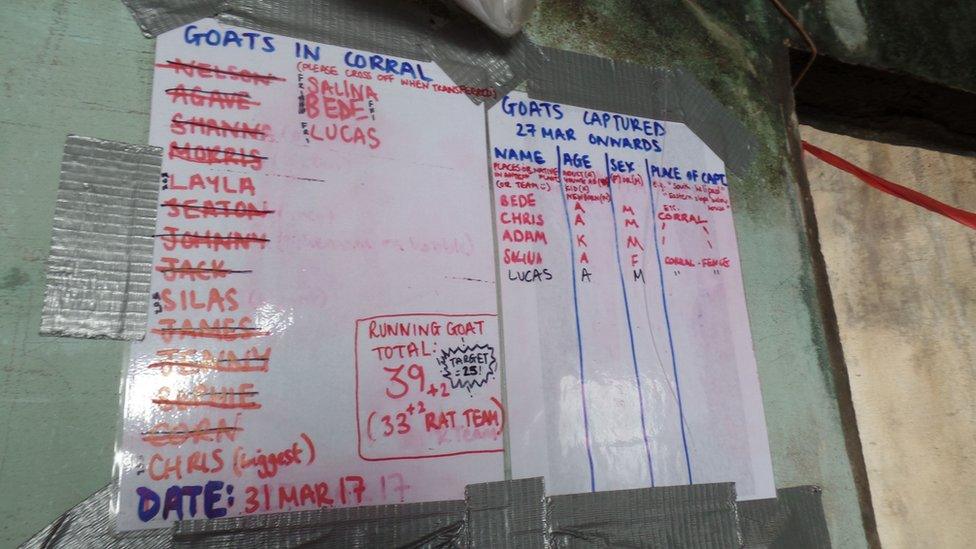

Today, half a dozen more are in a corral awaiting embarkation to the mainland. The government's department of agriculture plans to breed them for their useful, drought-adapted genes.

Also in conservationists' targets are thousands of black rats, which they plan to eradicate. The rodents arrived with a 19th-Century guano-mining community and have come to prey on wildlife, eating precious birds' eggs.

The goats have eaten most of the island's vegetation

For the handful of international non-governmental organisations at work here, in conjunction with the Antiguan government and the country's Environmental Awareness Group, Redonda is something of a giant outdoor laboratory.

"We will be watching to see what grows when all the goats and rats are gone," Elizabeth Bell, of Wildlife Management International Ltd, tells the BBC. "In Columbus's day, Redonda would have been completely covered with ficus trees. In five to 10 years, I think we will see reasonably interesting changes. Within 100, there will be massive change."

A board lists the island's goats, which have all been named after people

She said her ideal scenario would be to see it "fully forested again, with a larger population of boobies and frigate birds, lizards everywhere, and a massive increase in ground birds".

The island is also home to an endemic pygmy gecko, a species that was only discovered in 2012.

The team eventually hopes to reintroduce long-departed iguanas and burrowing owls too.

Redonda is known as an important seabird habitat

Under international conservation protocol, it takes two years before the island can be declared a rat-free zone. The painstaking eradication project involves laying rat bait, flavoured with everything from liquorice to chocolate, in every crevice. The spots hardest to reach are accessed by abseiling and snorkelling.

Redonda's dramatic deforestation has also triggered soil erosion and landslides threatening nearby coral reefs, says Shanna Challenger, a coordinator of the $700,000 (£540,000), three-year programme.

Salina Janzan, from Surrey in the UK, is one of several environmentalists camping out among the relics of stone buildings left over from the guano miners.

Conservationist Salina Janzan looks out over the make-shift camp

She said she had accepted the challenge to come as part of a delegation from the Fauna & Flora International (FFI) charity, partly because she had read a children's book called The Dragon of Redonda about the island when she was young.

"What do I miss most?" she says, with a grin. "A cold drink. In fact, anything cold. And proper showers. This is the longest anyone has lived on Redonda in decades."

Eccentric though it may sound, this is not the first time a project of this kind has been undertaken.

FFI says it has already eliminated black rats from 23 Caribbean islands since 1995, including 15 of Antigua & Barbuda's offshore isles. The work is believed to have saved the Antiguan racer, once the world's rarest known snake, from imminent extinction.

"Redonda is a pretty incredible place, both for the human history and the natural history," Ms Bell adds. "To be working to make it even more special is magical."

- Published15 September 2016

- Published11 September 2016

- Published19 February 2017

- Published25 August 2023