Nelson's Dockyard: From 'vile hole' to national treasure

- Published

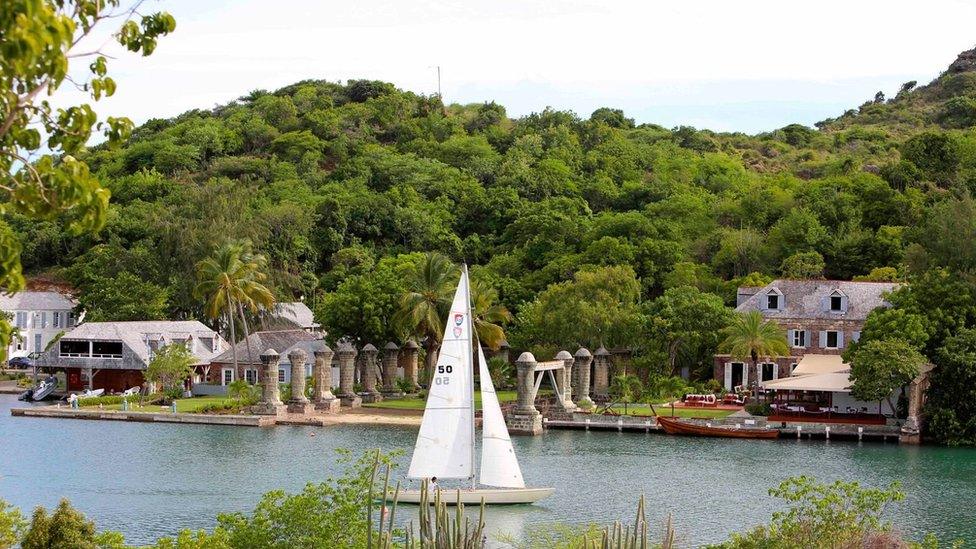

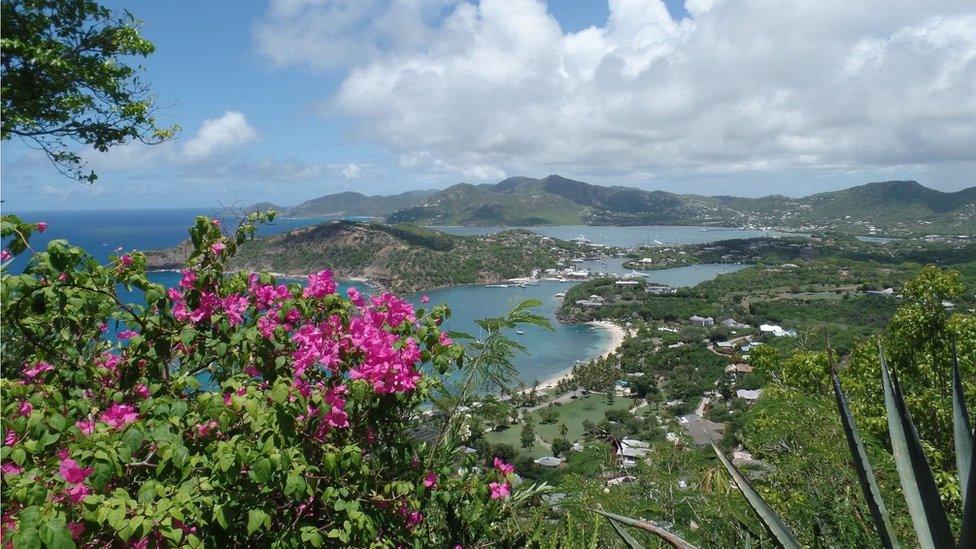

Nelson's Dockyard still boasts many colonial-era buildings

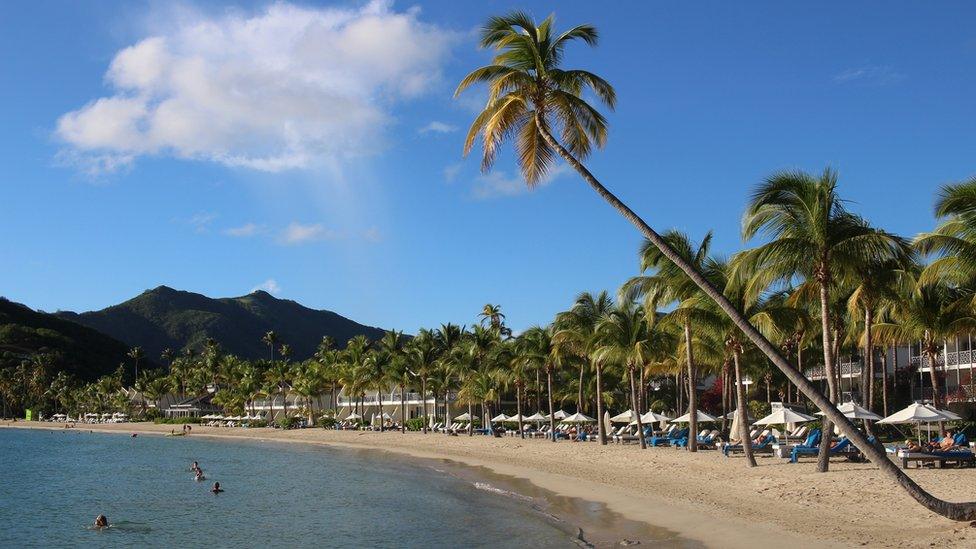

With its elegant colonial buildings and whimsical charm, it is hard to imagine how the Western Hemisphere's only working Georgian dockyard was once described by Lord Nelson as a "vile hole".

Two centuries have passed since the British admiral last laid his bicorn hat down here.

But Nelson's Dockyard in Antigua still conjures up evocative images of its 18th-Century position at the helm of imperialist Britain's crusade for wealth and power.

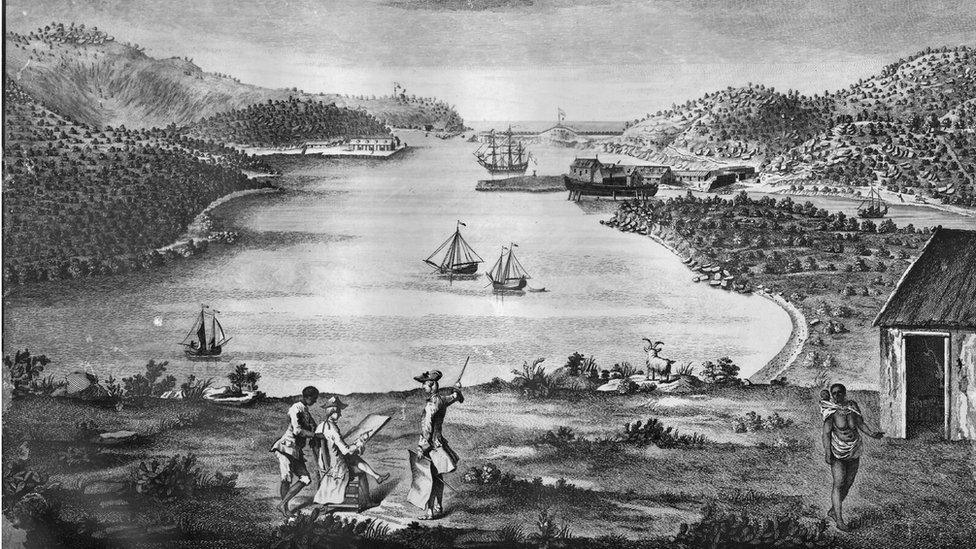

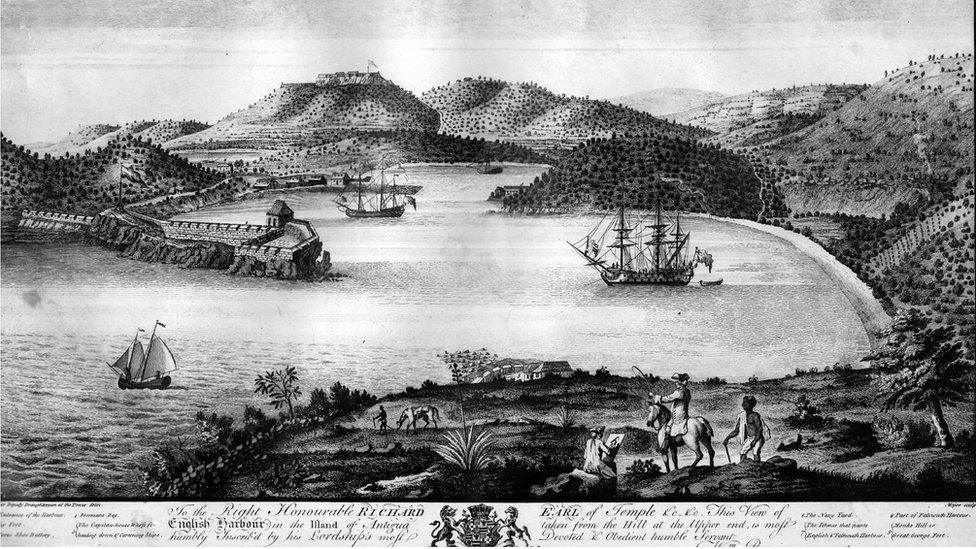

A drawing of English Harbour from 1756 shows it was busy with ships

Royal Navy ships such as HMS Blanche docked at Nelson's Dockyard in the 1870s

Built by enslaved Africans during the Age of Sail, its function was to maintain Royal Navy warships protecting Britain's valuable sugar-producing islands.

Today, it is home to several of the globe's most prestigious regattas and is a lynchpin of the Eastern Caribbean country's tourism product.

Time capsule

After the sugar industry waned in the mid-19th Century, Britain turned its attention elsewhere and the dockyard was closed in 1889.

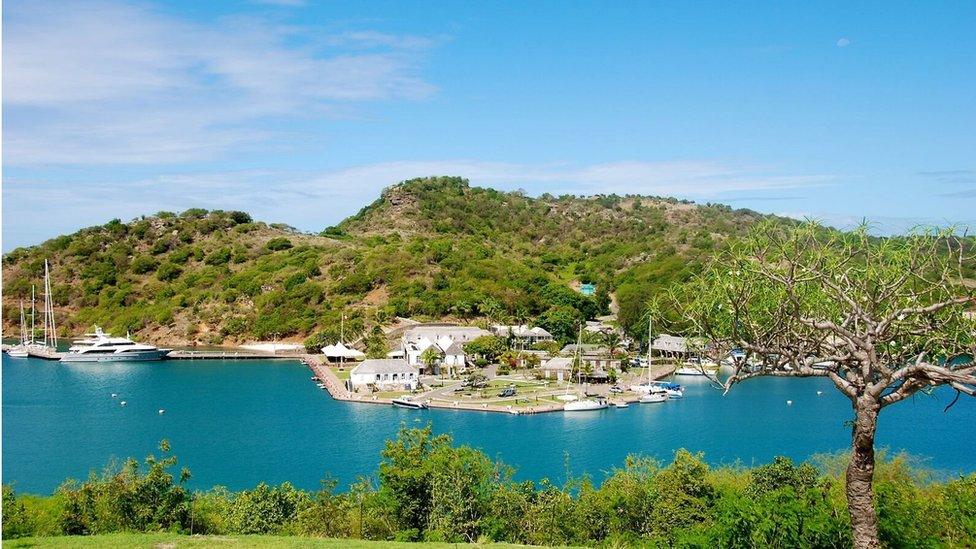

Nelson's Dockyard is now a Unesco World Heritage site

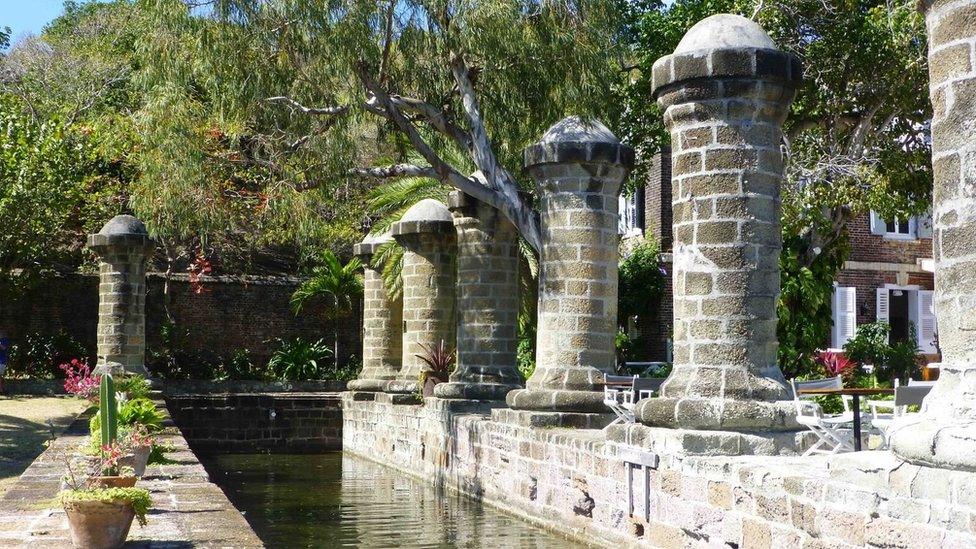

The sail loft pillars are a remnant of the dockyard's colonial past

But its abandonment, save for a clutch of local boat builders, would become its boon, resulting in an architectural time capsule of maritime glory, complete with stately stone pillars and abundant artefacts, and flanked by original fortresses.

United Nations cultural agency Unesco, which in July awarded it World Heritage Site status, concluded that there is nowhere else like it in the region.

Nelson's Dockyard

After it was abandoned by the British Navy in 1889, Nelson's Dockyard was battered by hurricanes and earthquakes over the next 60 years.

It underwent major restoration in the 1950s and was officially named after its famous erstwhile resident.

Nelson allegedly had six pails of salt water poured over his head each day at dawn as part of his morning ablutions while living in English Harbour.

He was unpopular with Antiguans but Nelson apparently treated his officers well - encouraging dancing, cudgelling matches and amateur dramatics during hurricane season.

Sailors' graffiti believed to date back to the 1740s can be seen etched into a wall on the fringes of Nelson's Dockyard.

Rum - a by-product of sugar - was once used as a 'cure-all' for the fevers and ailments associated with life in the tropics. By the 1730s the British Navy adopted a daily ration served to each sailor at noon.

Nelson was said to be so ill with fever on his voyage back to England in 1787 that he had a cask of rum shipped for his body in case he died en route.

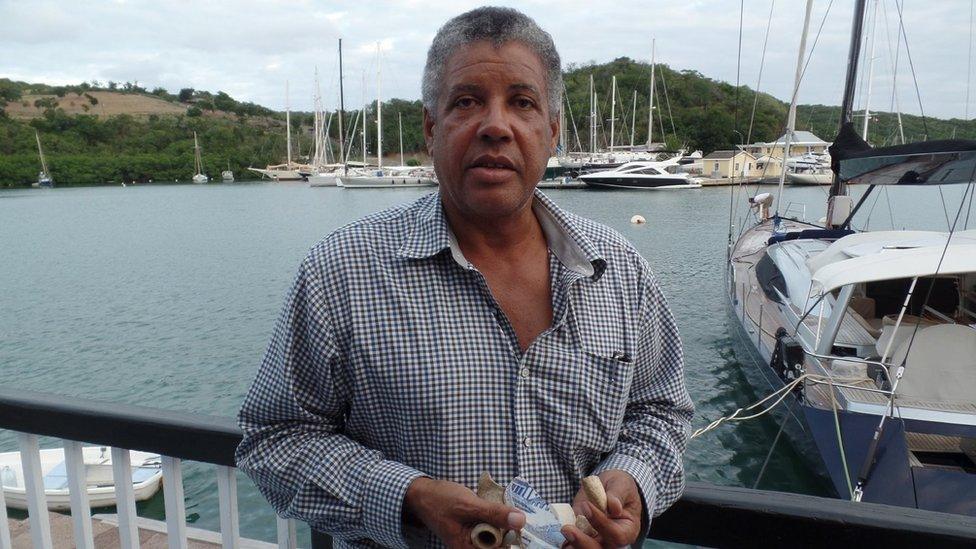

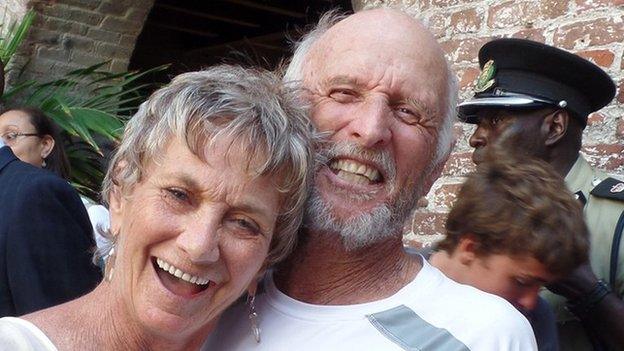

Antigua's Unesco representative, local historian Reg Murphy, described the accolade as a "huge bonus" for the nation of 90,000 people.

"I think it's the biggest thing that's ever happened to this island," he told the BBC.

"It means the dockyard is recognised worldwide as being of outstanding importance. Our small developing country can now stand head to head with the Taj Mahal, the Grand Canyon and the Pyramids of Giza.

"For tourism purposes, it's a marketing tool you can't pay for."

Protecting Britain's assets

Mr Murphy said the rigorous application process included detailed definitions of every structure, along with comprehensive management and conservation plans for the sprawling area which also includes several adjacent archaeological sites.

Reg Murphy says it has been a "huge bonus" for Nelson's Dockyard to have been awarded World Heritage status

He explained that construction at the dockyard began as early as the 1720s but its strategic importance increased after Britain lost the American War of Independence.

Suddenly it had two new enemies in the United States and its ally, France.

"Sugar from the Caribbean was funding the Industrial Revolution and the development of Britain. With warships sailing around the region, Britain had to protect her assets and keep her ships safe too in a place where they could be properly serviced and cleaned," Mr Murphy said.

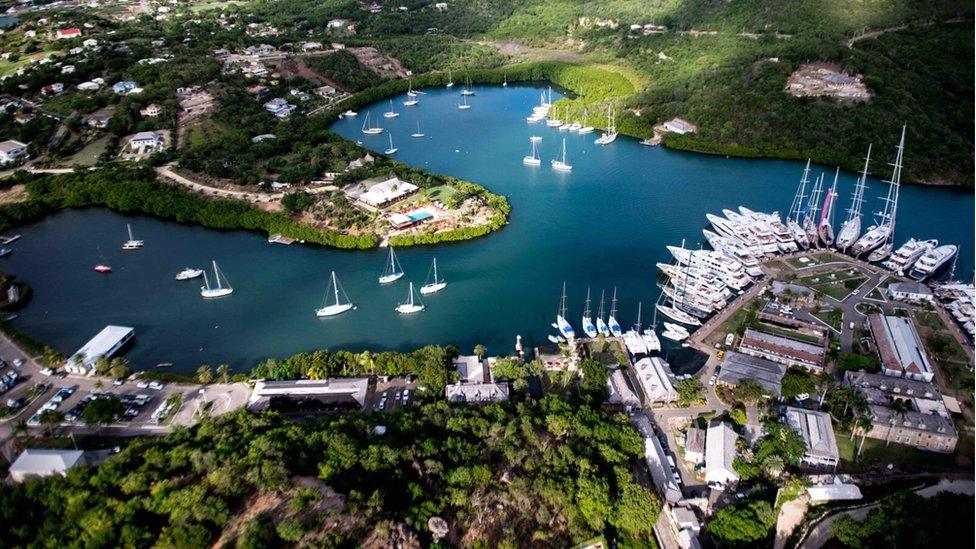

The deep narrow bays of Antigua's south coast, surrounded by highlands, create natural harbours offering shelter from hurricanes.

Boats used the natural harbours to shelter from hurricanes or attack

An aerial view shows the harbour's natural assets

"No other island has that," Mr Murphy said.

"Britain had a huge military advantage as it was able to keep its fleet there during hurricane season while every other country had to send theirs back home."

Strategic location

Antigua's geographical location, at the gateway to the Caribbean, also offered control over the major sailing routes to and from the rich island colonies.

The natural harbours once provided shelter for British warships during hurricane season

It was a year after the War of Independence ended that the dockyard would receive its most illustrious resident.

A reluctant Nelson was sent by Britain to enforce the Navigation Act which barred foreign ships from trading with British colonies and made him hugely unpopular with local merchants who depended on trade with the fledgling United States.

Nelson is said to have spent much of his three years there in the cramped quarters of his ship, the 125ft (38m) frigate Boreas, declaring Antigua to be an "infernal hole" and lamenting in letters back home of melancholy and mosquitoes.

These days, the dockyard is a vibrant vestige of the island's colonial legacy thanks to the major restoration programme.

It features original sail loft pillars and numerous buildings such as the 1789 Copper and Lumber Store, now a hotel by the same name, the former Naval Officer's house, now a museum, officers' quarters, guard station and even a small bakery dating back to 1772 which still contains three ovens that once supplied the compound with fresh bread.

The Copper and Lumber Store is now a hotel

Also included under the Unesco designation are various fortifications which were constructed to protect the area from invaders.

Among them is Shirley Heights Lookout, a favourite tourist haunt on account of its spectacular panoramic views.

The restored military lookout and gun battery at Shirley Heights are now a favourite with tourists

Galleon Beach, a former burial site for British sailors who fell victim to 18th-Century yellow fever outbreaks, also falls within the boundaries.

The latter was only discovered when a 2010 hurricane uncovered remarkably well-preserved human remains paving the way for an extensive excavation project.

A former burial ground for 18th-Century British sailors also falls within the Unesco area

For this unique district where past and present collide, the Unesco award enforces strict oversight and severely limits future development to ensure the preservation of a place which encapsulates a crucial point in history.

- Published28 February 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published27 December 2015