Why Venezuelan parents are keeping their children at home

- Published

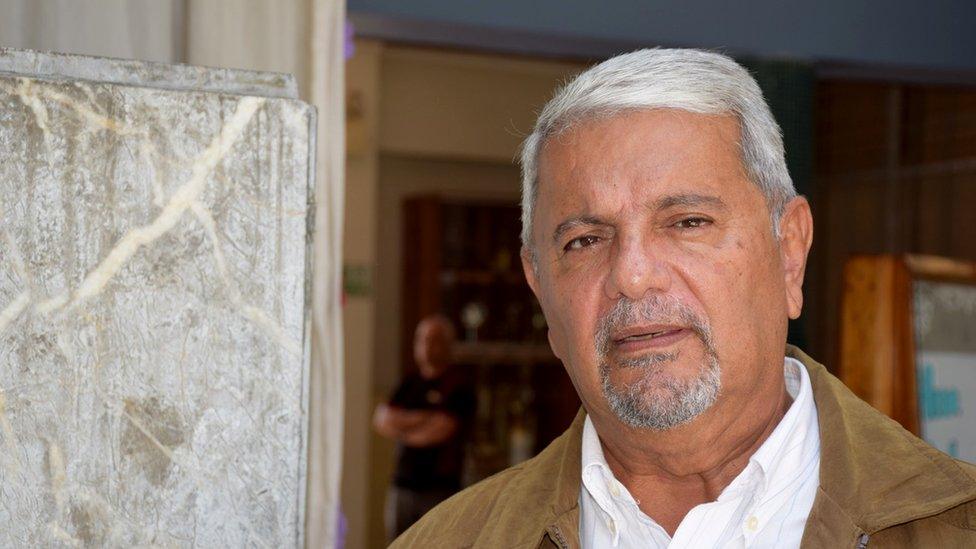

Andrew Páez and his wife Sara Yépez are not sending Manuel and Mathias to school

Venezuela is gripped by an ever-deepening economic and political crisis that has triggered almost daily anti-government protests since April.

Triple-digit inflation, a high crime rate and clashes between protesters and security forces have affected the lives of many, including schoolchildren.

"We're not living in normal times," says former professional football player Andrew Páez, 48, who has decided to keep his two sons at home.

Manuel, 12, and Mathias, 10, have not been to school since 19 April. "Our priority at this point is to keep them safe," Mr Páez says.

Mathias and Manuel attend La Salle Education Centre, a private school run by the Christian Brothers Catholic religious order in the western town of Mérida.

On that day, director Javier Ramírez tells me, the school was closed for independence day, but he was in his office doing some grading.

Javier Ramírez was doing some grading when protesters took refuge in the school

Outside, anti-government protesters were marching.

When Mr Ramírez heard some noise and went to investigate, he found a group of about 40 demonstrators had taken shelter inside the school after police had tried to disperse them.

Some of them had been injured.

Read more:

Mr Ramírez called the local emergency services, who took away those too badly wounded to walk, and then he asked the remaining protesters to leave, which they did peacefully.

'It was terrible'

Not long after, however, a group of six people forced the locks on the main gate and broke into the school grounds on motorcycles.

Brother Freddy, one of the Christian Brothers teaching at the school, lives in a house on the grounds.

Brother Freddy was threatened by members of a motorcycle gang

After helping tend to the wounded protesters, Brother Freddy returned to the house.

There he was with his sister, a school administrator, and her husband, when the motorcycle gang broke through the main gate.

"Some were masked, others not, some had weapons such as bats, others did not," Brother Freddy recalls.

"They broke the windows of all the cars parked here and ripped out their radios and sound systems, bashing the cars as they went."

The gang broke down the doors of the building where the Brothers live

While the gang broke down the door, Brother Freddy and three other people took refuge at the top of the stairs

"Not satisfied with that, they broke down the door to the house, smashing everything in their way."

"It was terrible. I thought, when they get to us they're going to give us a bashing, too," Brother Freddy says.

"I was standing on the top of the stairs, with my hands in the air and my eyes closed as two of them came up the stairs."

The gang took all the food it could and destroyed things they could not carry with them

The two told Brother Freddy to hand over his phone, which he did, and then one of them gave a signal and they all left.

"They took everything, all the food, and what they couldn't take they destroyed, such as the microwave. "They even overturned the pots with the plants!"

Rampage out of revenge?

Brother Freddy is convinced that the group was organised and suspects that its members were part of a "colectivo", the name given to pro-government militant groups.

Clashes between anti-government marchers and colectivos are not unusual at marches.

Mr Ramírez thinks the intruders may have been searching for the protesters who had earlier taken shelter in the school, and that when they did not find them they went on the rampage.

The building where the Christian Brothers live is still being repaired after vandals damaged it

He reported the incident to the authorities and police are investigating.

The mayor's office sent three guards to protect the school in the aftermath of the attack and while the main gate was being fixed.

The school re-opened on 24 April.

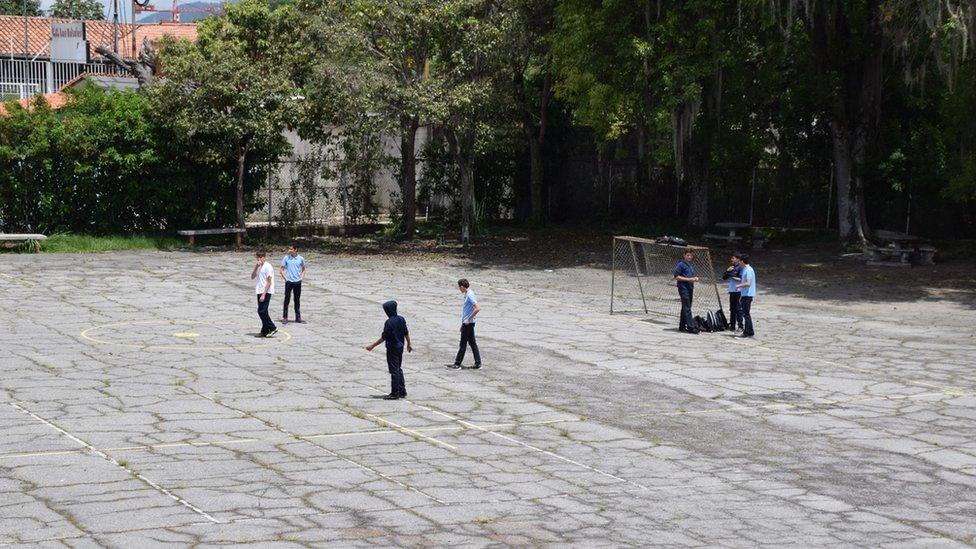

Classes have restarted but on the best of days only 60% of students turn up

But Mr Ramirez says that at least 40% of the school's 704 students are not attending class out of fear a similar incident could happen again.

'Can't carry on as normal'

Manuel and Mathias are among those being kept at home.

Manuel says he was very sad when he heard about what had happened. "How can it be that someone would attack a school just because it sheltered some people?" he asks.

A keen footballer like his father, he has been using his free time to train.

His younger brother Mathias is also fed up with the situation in Venezuela.

"It's been two years since I've had any Nutella," he says of the shortages of imported goods.

Their mother, Sara Yépez, says she just does not want to run the risk of them getting hurt in school or on the way there.

Sara Yépez says it is time to stop carrying on as normal

But it is not just that, she says. Like her husband, Andrew Páez, she believes that the situation in Venezuela has deteriorated so much, drastic measures are called for.

"Normal life has ceased, and if we want our children to have the opportunities they once had, we need to stop carrying on as normal," she says.

"And if that means that our children may have to repeat a year, so be it."

'You can get hurt at any point'

"At any moment you can get hurt, you can get robbed and your salary does not cover the basics, even if you can find them," she says of Venezuela's rampant crime rate and its hyperinflation.

Lina Contreras, an independent business woman who has a 17-year-old son at La Salle school, agrees.

Lina Contreras says children will be affected by missing class but it is a sacrifice she is willing to make

"We want to send a message to the country that we can't send our kids to school when other young people are giving their lives on the streets," she says referring to the protest in which dozens of people have been killed over the past weeks.

Andrew Páez says that what his sons are missing out on in terms of schooling is made up for by what they are learning as individuals.

"Ethics and values are more important at this point," he says.

They also try to ensure that the children keep up with the curriculum.

After teaching mechanical engineering at the University of the Andes, Sara Yépez rushes home to sit down and study with Manuel and Mathias.

They say they are lucky to have someone to help them look after them when they are both at work.

As owners of their own company, Lina Contreras and her husband have also been able to adapt their schedule enough to make sure someone is there for their son at key times.

All three say it is a sacrifice they are willing to make.

Stay or leave?

Not all parents agree with the stand Lina Contreras, Andrew Páez and Sara Yépez are taking.

More than half are sending their children to La Salle whenever the roads around the school are not blocked by protests, not wanting them to miss out on their schooling.

These days, the school yard is rather empty

Others just do not have anyone who can look after them while they are at work.

But they, too, are worried by the security situation and many have had to leave work to collect their children from school early when a march passed nearby.

With no end to the protests in sight, Andrew Páez and Sara Yépez say they may have to consider leaving Venezuela altogether, as 17 of their nieces and nephews have already done.

Lina Contreras says she is optimistic that the protests will bring about a change of government and that her son may be able to graduate this year as planned.

- Published11 May 2017

- Published14 May 2017

- Published22 May 2017