Colombia: Searching for an alternative to coca

- Published

A farmer cuts back weeds on his coca plantation in La Carmelita

In the remote region of Putumayo in southern Colombia, the economy depends almost entirely on one thing: coca, the raw ingredient for cocaine.

From the stores that sell fertiliser and pesticides, to the ubiquitous pool halls where "raspachines" (field hands who harvest the coca leaves) come to spend their modest earnings on cold beer and fried empanadas, it all comes back to one plant.

Colombia's government wants to change this, as part of the peace deal it reached with the country's left-wing rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) last year. It will not be an easy task.

"Everyone from here who has gone to university has done so because of money from growing coca," explains Jon, who has been harvesting the leaf since childhood and is now studying forensic science at a technical institute in Mocoa, Putumayo's capital.

A "raspachin" (field hand) takes a break from processing coca leaves in the jungle of Putumayo

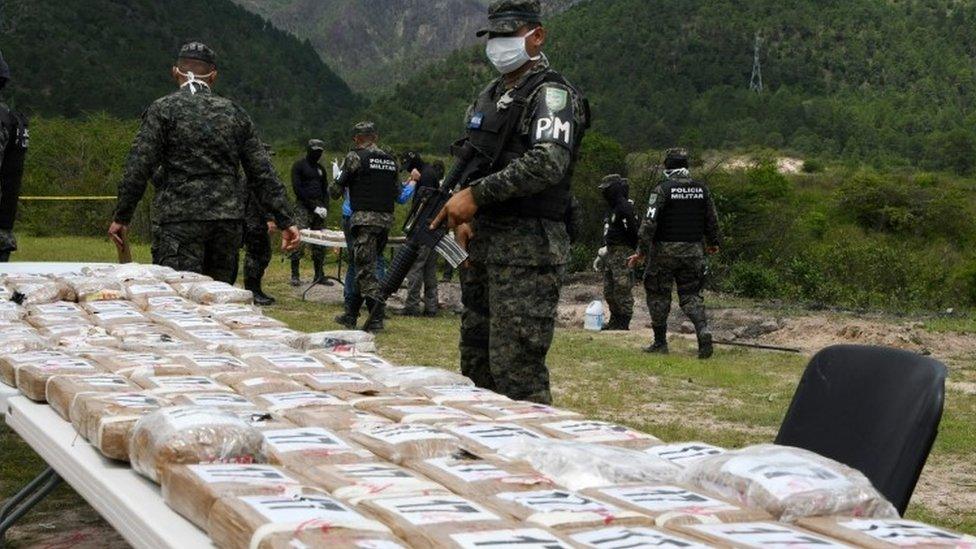

As per the terms of the peace deal, the government has signed up almost 76,000 families to an ambitious campaign to substitute the growing of coca, poppy and marijuana with legal agricultural projects.

Jon's family was one of 500 selected from the communities around the village of La Carmelita to participate in a pilot of the national programme.

Read more:

Success, in the long term, will depend not only on the viability of the new crops, but on the state's ability to transform its relationship with the marginalised regions where the 50-year armed conflict raged.

"For years, we've made clear that we're committed to leaving coca behind, given certain necessary conditions for our survival," said Luz Deify Velázquez Quintero, a community leader in La Carmelita.

Residents of La Carmelita hope the government is committed to the programme

"Now it's time to find out if the government is serious."

Deep-rooted scepticism

This is not the first attempt to wean Putumayo off growing coca.

La Carmelita residents saw little of the money earmarked for "alternative development"

Under the US-backed Plan Colombia, the authorities attempted to eradicate the plants from the air by spraying them with herbicides.

Hundreds of millions of dollars were also channelled to the country for "alternative development" assistance, resources that locals say rarely found their way to Putumayo and the pockets of farmers there.

While the new programme is largely welcomed by La Carmelita's coca growers, distrust of government programmes is an all-too-familiar sentiment.

"Unless there's transparency and a real willingness to involve and empower the communities, what's most likely is that people end up going back to coca," warns Yuli Zuluaga, a regional representative of a recently formed national coca-grower's association.

Peace brings new opportunities

Government officials say they have learned the lessons of Plan Colombia. They think that having former Farc rebels on board will make a big difference.

The rebels financed their armed struggle through "taxes" on coca production and therefore had a vested interest in the business flourishing.

But even with a peace process now firmly in place, challenges remain.

In June, participants in the pilot scheme received the first of six bimonthly food subsidies worth 2m Colombian pesos ($665; £500) each.

In exchange, those who received it have promised to take part in a two-month voluntary coca eradication scheme.

The border village of Teteye, just 20km from La Carmelita, has no electricity, water or sewerage system

But whether the farmers' new projects will be productive will ultimately depend on whether money is invested in Putumayo's poor healthcare, education, and infrastructure, conflict monitoring group Ideas for Peace Foundation, external concluded in a recent report.

There are no hospitals or drinking water and only little electricity for miles in any direction from La Carmelita.

The only adequately funded public institutions are the military bases built to protect the region's oil pipelines.

"The problem isn't figuring out what to produce," explained Jesús Antonio Toro Martínez, president of Agropal, a local farmer's association.

Jesús Antonio Toro Martínez has left behind coca farming to grow plantains

"The problem is that we don't have electricity to store it, we don't have the equipment to process it, and we don't have roads to bring it to market. In other words, we don't have commerce."

Mr Toro, a local farmer and former "raspachin", says that taking plantains to the nearest urban centre if Puerto Asís is no easy task.

He says that the costs for transporting bundles on speed boats or local buses known as "chivas" can add up to as much as 90% of the final sale value.

A volatile environment

In March, the US released figures suggesting that a record 188,000 hectares (1,880 sq km) of land in Colombia had been planted with coca last year, an 18% increase compared with 2015.

The government hopes La Carmelita residents will move away from planting coca for good and dedicate themselves to other trades

The report triggered renewed claims from opponents to the peace process in Colombia and conservatives in Washington that the government's reformist approach has promoted lawlessness.

With pressure mounting and the 2018 national elections looming, President Juan Manuel Santos announced that he intends to eradicate 100,000 hectares by next year, half through substitution, and half through manual eradication.

"We need results, to prove to ourselves, to the country, and to the world that this is the right way forward," Miguel Ortega, a government substitution official, told La Carmelita residents.

Camilo Mejia, external is an Australia-based journalist and co-founder of Vela Colectivo, external. Steven Cohen, external is a US-based journalist and former editor at Colombia Reports, external.

- Published15 July 2017

- Published28 January 2017

- Published1 November 2016

- Published23 October 2016

- Published4 February 2016