Modern slavery: 'I had to eat the dog's food to survive'

- Published

It was already late when Maria, alone in her room, thought about taking her own life by jumping from the seventh floor window. Her day at work, just on the other side of the door, had again started around dawn and only ended 15 hours later. She felt weak, having not eaten for two days.

Maria (not her real name) had arrived in Brazil from the Philippines two months earlier, hired as a domestic worker by a family who lived in a wealthy neighbourhood of Sao Paulo.

The tasks they set her seemed never ending.

She had to help the mother with the three school-aged boys and a baby. Then clean the large apartment, which had a large dining room, a living room and four bedrooms, each with its own bathroom. Also walk the family's dog, put all the children to bed.

The family's mother usually stayed at home, closely watching everything Maria did. Once, complaining that Maria had not cleaned a glass table properly, she made her polish it for almost an hour. Some days she would count the clothes Maria had ironed and, not satisfied, would make her spend hours ironing some more.

Weeks would pass without Maria's employers giving her a day off. With so much to do, she often had no time left to eat. Sometimes, even the food she was given was not enough.

On that night, she thought about her own family in the Philippine countryside: her mother and three young daughters, two of whom needed special medicine for their cardiac disease. With all of them depending on her wages, Maria had no choice but to carry on. So she made her bed and went to sleep.

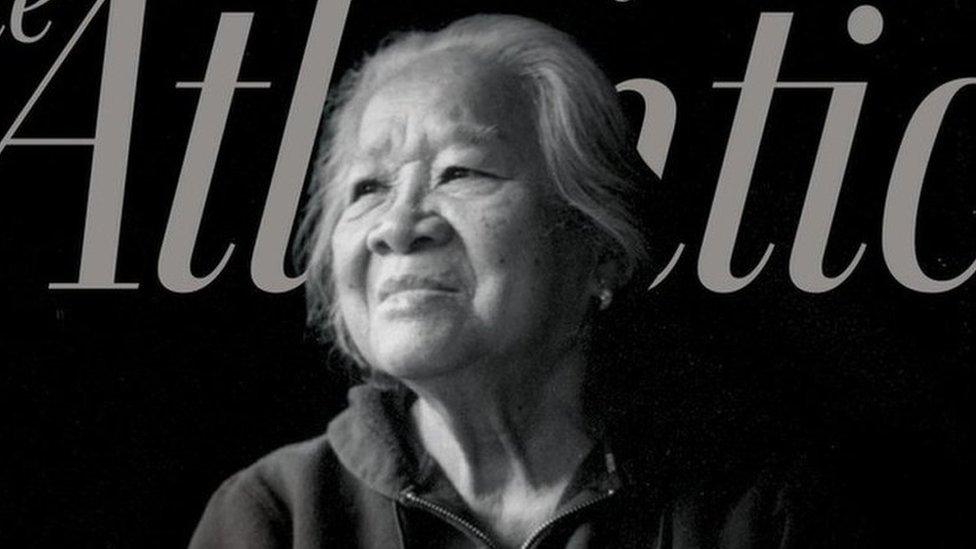

"My world was spinning. I was crying," recalled the 40-year-old about the day she almost ended her own life. She had dreamt of coming here - "I had heard that Brazil was nice" - and struggled to understand why she was being treated so badly.

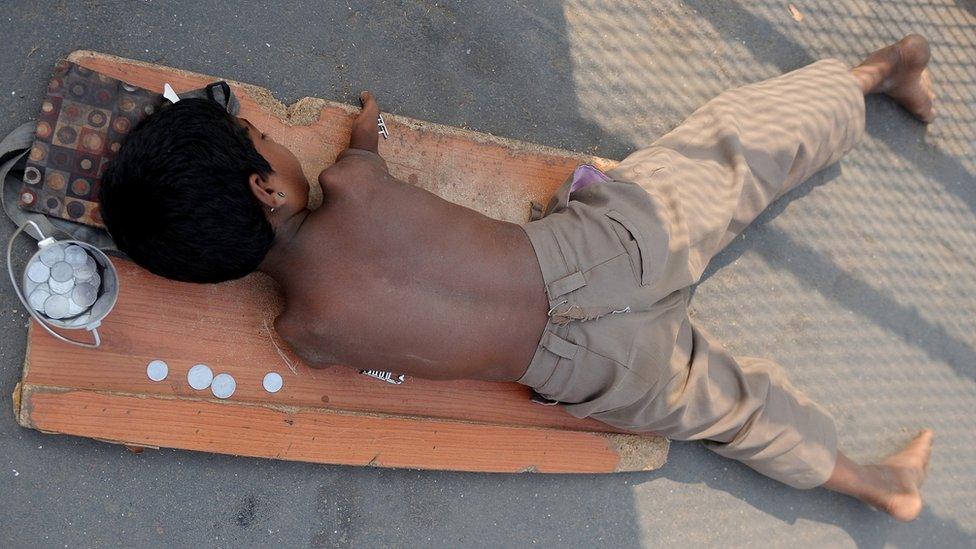

When Maria woke up the next day, her stomach hurt from the lack of food, but her tasks were already waiting for her. Only hours later did she find something to eat: she was cooking meat for the family's dog and took half of it for herself.

"I didn't have [any other] choice to survive."

Maria's case is not unique.

Brazil has the world's highest number of domestic workers, and some six million Brazilians are employed by middle-class and rich families. Many suffer abuse and prejudice, and officials say some are kept in conditions that amount to modern slavery - it is hard to estimate how many as government data related to these cases is almost non-existent.

In 2013, Brazil finally started introducing legislation to give housemaids the same rights as every other worker, such as an eight-hour working day, a maximum of 44 hours of work per week and the right to overtime pay. Most, however, still work informally.

Those rights, Maria said, were part of the attraction of coming to Brazil. She was also promised what she thought was a decent monthly wage ($600; £460) and longed for the chance to explore a new country.

A kind, smiley woman, she had already worked as a live-in maid in Dubai and Hong Kong without having problems, and never imagined she would have any trouble in Brazil.

When Maria lost hope that her working conditions would improve, she challenged her employer. "I asked 'Why are you always like this to me?'" Her employer, she recalled, said disdainfully that she had never liked Maria.

Maria was rarely alone in the apartment. But one night the family went out and when Maria checked the doors, she found them locked. As the apartment was in a highly secure building, it was unusual for the front doors to be locked. The fact that they were when she was left alone made Maria wary.

That was a turning point. She decided she had to escape.

The next morning, she got up before anyone else, and finding the door unlocked, she left. Concerned that the building's security guard may become suspicious seeing her leaving with her luggage and alert her employers, she purposefully and jauntily waved goodbye at the security camera.

The trick worked and Maria got away unchallenged. She was still jubilant: "I was lucky".

Millions of people from the Philippines work abroad, mainly in neighbouring Asian and oil-rich Middle Eastern countries, to support their families. But frequent cases of abuse have put the spotlight on how they are treated.

In Brazil, three other Philippine maids who were recruited by the same agency as Maria also left their employment in the last year under similar circumstances.

They were helped by Father Paolo Parisi, who runs the non-governmental organisation Missao Paz. "They were crying, their dignities had been destroyed," he said. "I told them this was exploitation."

Maria and the other three Philippine maids paid $2,000 (£1,500) in fees to the agency. Their employers paid the agency $6,000 and the cost of the flights to Brazil.

What they were not told when they applied for their jobs was that their visas would be tied to their employment. So even when they found conditions to be bad, they felt they could not just walk out and look for a new job. And to get a new work permit, they would have to leave Brazil.

About 250 Filipinas have been hired to work as maids in Brazil since the end of 2012, when legislation paved the way for families here to hire foreigners. Many Brazilians say they prefer Philippine maids because they are well-trained and speak English, and so their children can grow up in a bilingual environment.

But there might be more to it, said Livia Ferreira, an inspector at Brazil's Labour Ministry in Sao Paulo.

"I think these families started hiring these workers to exploit them," she said. "They couldn't find [Brazilians] that would be at their disposal... The changes in legislation empowered housemaids and they weren't accepting certain working conditions anymore."

Ms Ferreira's team concluded that Maria and the other three Philippine maids had been kept in slave-like conditions - Brazilian law defines it as forced labour, work in degrading or risky conditions, without pay or to pay off debts owed to an employer.

"Their working conditions were very different from what they had been promised. They were kept in forced labour and had exhausting routines," Ms Ferreira said.

The employers, who have not been identified, have not commented. Brazil's public defender's office has launched labour lawsuits against the families and the recruitment agency. The agency denies any wrongdoing and has suspended its recruitment service.

The authorities are now looking into the situation of 180 other foreign domestic workers, and some labour law violations have already been found in the first cases.

Maria has found a new job after the government gave her and the other Philippine maids new visas. But her life is not without fear. Two months ago, the flat she moved into was ransacked. Nothing was taken but Maria saw it as a warning.

Most of what Maria earns goes towards paying off debt she got into to pay the agency which first placed her in Brazil. She hopes to save money to send her daughters to university - "so they don't follow in my footsteps" - and to open her own business when she returns home to the Philippines.

But for now, she is finally enjoying her life in Brazil. "I feel free. I'm happy now."

Video by Ana Terra Athayde; Illustrations by Katie Horwich

.

- Published20 May 2017

- Published31 May 2016