100 Women: Playing mother to El Salvador's gang children

- Published

The children left behind have no official documentation. The new 'mothers' often don't even know their real names or how old they are

El Salvador has one of the highest rates of murder in the world, according to the UN, driven in no small part by gang culture. It is often the women in El Salvador's communities who bear the brunt of the threats and violence these gangs bring - and now the gangs have found a new way to intimidate and control them.

An unexpected knock at the door turned Damary into a new mother, instantaneously.

One evening, she was having dinner in front of the television, when a visitor turned up at her home. The 23-year-old put aside her bowl of beans and rushed to open the front door.

Standing there, Damary found a man, a gang member, holding a baby wrapped in green rags.

He was almost a child himself, barely 16 years old.

Thin and tanned, he passed Damary a phone: "Someone wants to talk to you."

On the other end of the line, she recognised the voice of a local gang member, who'd been jailed less than a year earlier.

"You know whose baby she is, so make sure you take good care of her," the gang member threatened her.

"If anything happens to the child, we'll be watching you,"

These 'mothers' can't move house or travel with the child without the gang's approval

The girl in her arms was so small, Damary thought she couldn't be more than five days old.

She went back to her living room without asking any more questions, sat down and started to cry; she'd just "had" a baby.

Her mother, who had been putting Damary's three-year-old daughter down for the night, came out of the bedroom. They talked about how they were going to cope with two children and no work.

Her mother told Damary to resign herself to her fate - best to look at the new "daughter" as a blessing.

And with this, they went to bed.

Back when she was a mother of one, Damary could at least manage. Her own mum helped out and Damary could still go to school.

But with two girls, things changed. Money was too tight; it made sense to drop out from school and tend to the children instead.

Time went by. Damary's new daughter is now two and has become one of the many children who run around, play and cry in this poor community of San Salvador.

She calls Damary "mama", but her life has never been free from uncertainty. There is still no official paperwork for the child, no birth registration. No-one even knows where she was born.

Damary made up a name and a birthday, so she could pass the girl off as her own. She still doesn't know how she'll manage when she has to enrol her at school, or if she ever needs to go to hospital - or what she'll say if the authorities ever demand an explanation.

Damary makes no distinctions between her daughters; she loves and cares for them equally. She combs their hair, buys them second-hand clothes and sings them to sleep. They look different but, to her, they are the same.

Gangs have been a feature of the country since the end of the civil war, almost 30 years ago

Damary and I are chatting in a playground when her phone rings.

She walks away and comes back a couple of minutes later, a forced smile on her face.

"A phone call from prison?" I ask.

"Yes," she says, looking from side to side. "I thought we'd been spotted, but it's just a call to check up on the girl."

She often gets phone calls from the gang member in prison. Like the cuckoo bird, he relies on others to raise his young - by manipulating a host to take care of its offspring as if it were its own.

Scientist believe, if the substitute mother bird tries to remove the unwanted baby cuckoo, the parent cuckoo will destroy the nest or harm the other chicks in revenge.

The cuckoo is never far from the host nest - ready to remind the "carer" of her imposed obligations.

The Cuckoo is watching Damary.

Gangs in El Salvador hold great power over poor communities such as this one and every time they pick a "nanny", her whole family's life is affected.

Analysts say the epidemic of gang violence, external in El Salvador was fuelled in the 1990s by the US deportations of MS-13 gang members.

One migrant living in the US state of Maryland told the New York Times, external that "the [Central American] country is infested with gangs".

"The moment we arrived, they would come to our door asking for money," said Noe Duarte, who runs two small businesses cleaning and painting homes.

"And if we didn't give it to them, we'd be killed."

These are not remote communities; police patrolling the streets. And yet, the gangs are in control

The first time I visited this part of El Salvador was in early 2016.

I can't reveal its real name - it would endanger the lives of the women who have been telling me their stories - so we'll call it "Barrio 18".

This is not a remote or isolated community. In fact, this place is not even far from the capital, San Salvador.

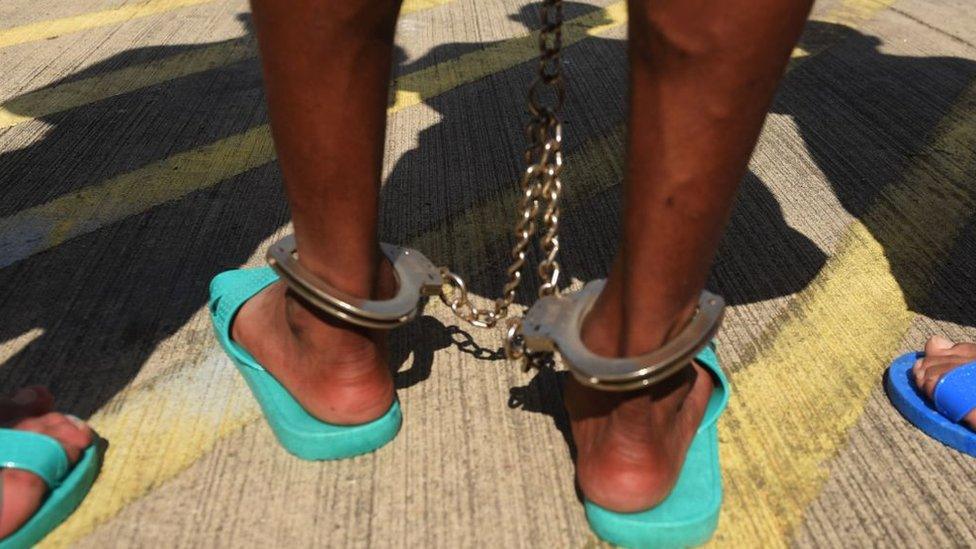

Police are often seen on the streets. Soldiers are on patrol here, regularly stopping and searching young men. At night there are raids and sometimes guns go off.

It would seem the authorities are in control - but they're not.

"Barrio 18" belongs to the Barrio 18 Revolutionaries gang. They control who comes, who goes, who pays protection money and, ultimately, who lives and dies.

The gang rules the community with an iron fist, deciding what clothes young people should wear, which school they should go to, what music can be played on the street and when people have to stop drinking alcohol of an evening.

These are unwritten rules but anyone living here is advised to learn them fast or pay the price.

Those who refuse, or get too close to the police or with rival gangs, don't live to tell the tale.

The gang is everywhere; the powerful "capos" are young guys - some still teenagers. Some, like the Cuckoo, are in prison.

Everybody knows who they are and people do as they're told.

'My mum is praying'

Just like Damary, Maria also became a "mother" overnight, although the child brought to her wasn't a baby, but an eight-year-old boy.

On Saturdays, Maria used to help out at an evangelical church. They had a children's group, where the kids would have some fun, learn a little and eat sweets.

Andres was one of the children in the group.

One day, no-one came to pick him up at the end of the session. She offered to drop him home, but when they arrived, there was no answer.

They called again later, and later still, but it was no good. Eventually, Maria took him home.

Prisons in El Salvador are often extremely overcrowded

The next day, she got a phone call.

"It was a man. He said that I was in charge of Andres now," she says.

"If anything happened to him, worse would happen to me. He said he knew my family. Taking revenge would be easy."

"Did you know who you were talking to? Did the man introduce himself?" I ask.

"He didn't have to," says Maria. "You just know who they are. You hear their voice and it's enough. It's terrifying.

"It's always 'them' and 'us'. They know how they can hurt me. There were times they would call and say nothing at all, just breathing hard down the line, to remind you that the beast is nearby."

In all the time she's been looking after Andres, only once has a woman phoned to enquire about the boy. The call was cut off.

"It might have been his mother. I think both parents are in jail," says Maria.

She already has children of her own and it hasn't been easy for her.

"My mum is praying for us," she says.

"She wants to help, but she can't do much. She tells me to accept the facts and take it as a blessing. Only she and my brother know where Andres really comes from.

"I am fond of the boy, but if I'm honest, I wish his parents would take him away."

Even when gang members are arrested, they can still exert power from prison

It is difficult to understand how many cuckoo families there are in El Salvador.

Factum, a Central American magazine that specialises in investigative journalism, has spent months researching this phenomenon in Barrio 18 and in two further locations; a community in San Salvador and another one in Santa Ana.

In Barrio 18 alone, Factum has identified at least 12 different cuckoo families, and has interviewed six women forced to look after the children of gang members.

Conna, the government agency that looks after children's rights, says they have no reports of such a practice taking place. In fact, Conna's deputy, Griselda Gonzalez says she has no knowledge of any cases.

If there were to be a case brought to her attention, Ms Gonzalez says the children would be taken away from the host families, since they cannot provide any official paperwork.

Women say removing the children in their care could condemn them to an almost certain death.

The main support these women get comes from NGOs operating in El Salvador's marginal communities.

To date, these organisations are the only ones who have looked into the "forced hosting" phenomenon and have drawn resources from international cooperation funds to try to alleviate some of the hardship.

Donald Trump's current administration has been pursuing vigorous deportation policies, withdrawing El Salvador migrants' right to remain in the US earlier this year.

Hundred of thousand migrants face possible deportation and many say they are at risk of gang violence if they return to El Salvador.

Critics of Mr Trump's decision noted that the US State Department's own guidance referred to El Salvador as home to "one of the highest homicide levels in the world".

"El Salvador is simply unprepared, economically and institutionally, to receive such an influx, or to handle their 192,700 US children, many of them at the perfect age for recruitment or victimisation by gangs," the aid agency the International Crisis Group said last month.

Little Tony

Tony is a "gang-child", living with a woman who is not his mother. Despite his age, he's already started to behave like a gang member. It's what he's used to.

He enjoys deferential treatment among the other "homeboys" - Salvadorean slang for a gang-member.

He's discreet, a boy of few words. He's got the arrogant gaze of a confident gang member and he never talks to strangers.

He's immune to bribery and knows the difference between his host family and his real family. He's in no doubt about who can - and who cannot - tell him what to do.

Tony only comes out of his shell when he's with the gang. They hang out together; they sit by the concrete court or on park benches. He laughs at their jokes.

Tony feels at home with the Barrio 18 gang and they treat him as one of their own - he's even got a gang nickname. He knows his dad is a member and he behaves as such.

Tony urinates on the street if he wants to. He fights, struts and disrespects his "host mother". Tony is a little gangster.

Tony is four years old.

Both his parents have been in jail since he was one, and Marcela was chosen to host him

The fact that Marcela is very young herself is irrelevant - she was picked and now she has to look after him. She must bring him up as her own, but under rules that the gang decides.

If Tony wants to spend his time on the streets, playing with the gang, she can't - and mustn't - stop him.

But now Tony is tired and falls asleep on her lap. She plays with his hair, fans him, rocks him. Marcela says one of the most entertaining things about little Tony is hearing him talk about his dad's exploits. He knows all the tales; the gang told him everything.

Like the other "gang-children", Tony has no official identity, no birth certificate and no ID card.

"He'll soon need to start school. How will you enrol him?" I ask Marcela.

"I'll see if I can find his birth registration in the town hall," she says.

"And how will you explain your relation to the boy?"

"They don't usually ask much. And if they do, I just say I'm his mother."

"And if you ever need to go to hospital with him?"

"I really don't know. I'll have to find someone to help, but I'll have to be careful he doesn't get taken away from me."

Until recently, gangs had three clear roles for women: "jainas" or girlfriends, collaborators, or sex slaves.

Now, they can also be "hosts".

Damary, Maria and Marcela all have something in common; the gang knew they'd make good mothers.

The gang found a new way of enslaving them, forcing them to bring up the "gang-children", or face death.

And just like that, their homes became a modern-day cuckoo's nest.

This is an abridged version of an article that originally appeared on BBC Mundo. Spanish speakers can read the full article here.

Bryan Avelar, writes for Factum, a Central American magazine that specialises in investigative journalism. This investigation was carried out together with El Intercambio, a local production company.

Names of people and places have been changed to protect the identity of those interviewed.

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. We create documentaries, features and interviews about their lives, giving more space for stories that put women at the centre.

Follow BBC 100 Women on Instagram, external and Facebook , externaland join the conversation.