Venezuela crisis: More migrants cross into Brazil despite attacks

- Published

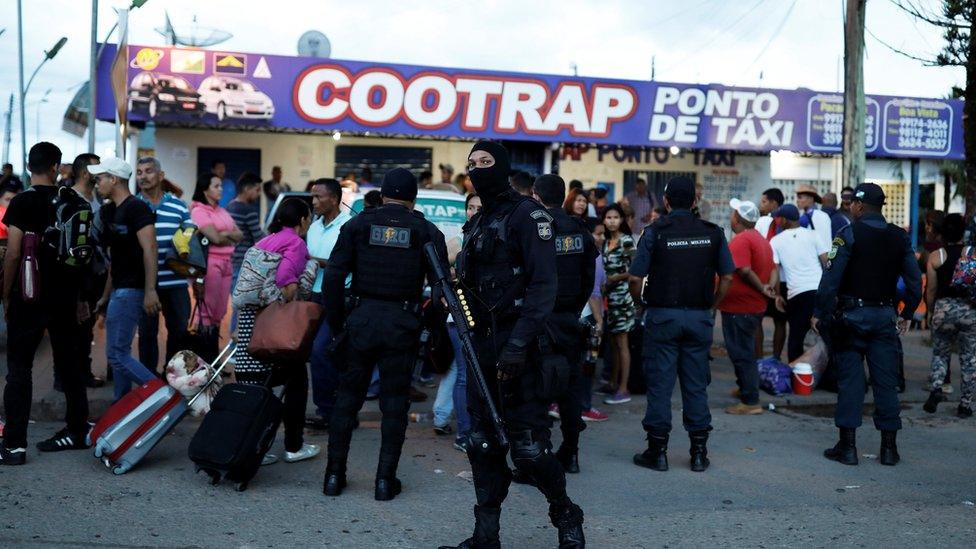

Venezuelans were queuing to cross in to Brazil

The number of Venezuelans entering Brazil is rising, officials say, despite Saturday's attacks on makeshift migrant border camps.

A Brazilian army spokesman said about 900 Venezuelans were expected in the state of Roraima on Monday, a steep rise in the daily average.

The numbers of people trying to flee Venezuela's economic collapse are stoking regional tensions.

There is fresh uncertainty following the issuing of new banknotes.

Banks and shops are due to reopen on Tuesday after a public holiday on Monday, when the left-wing government lopped five zeros off the bolívar and anchored it to a new virtual currency called the petro.

The government says the move is needed to tackle runaway inflation, but critics say it could lead to even more chaos.

Opposition groups have called for strikes and protests on Tuesday.

What is happening in Brazil?

Extra security forces have been sent to the border with Venezuela following violence near the town of Pacaraima on Saturday.

The Roraima state government has asked the Supreme Court to temporarily halt the entry of migrants from Venezuela, saying social services were being overwhelmed.

However, Brazilian Security Minister Sergio Etchegoyen said closing the border was "unthinkable, because it is illegal".

He said the presence of military police at the border had improved the situation.

"There's tension, but there's no conflict," he added.

Brazil has sent more security forces to quell any unrest in Pacaraima

Many of those crossing into Brazil say they are hungry and don't have access to medical services in Venezuela.

The army said that on Sunday about 800 Venezuelan migrants arrived in Roraima, about 300 more than the average number crossing every day for almost a year.

In Pacaraima on Saturday, several migrant encampments were attacked by angry residents following reports that a local restaurant owner had been badly beaten by Venezuelans.

Hundreds of migrants fled back across the border and gangs of men burned their camps and their belongings. Reports on Monday said many had since crossed back into Brazil.

There has been growing animosity towards the numbers of Venezuelans entering Roraima in recent months.

Underlying tensions boil over

By Julia Carneiro, BBC News, Pacaraima

There is no visible sign of Saturday's violence in Pacaraima. The city is quiet, the streets are clean. Firefighters have washed away the ashes from where Venezuelans had been living, their tents and belongings burned by protesters.

Many Venezuelans have left - but more keep coming.

On Monday, residents organised a "peace motorcade" to try to dispel the idea of intolerance. They said Venezuelans were welcome, but violence was not.

But as soon as I started speaking to Venezuelans about what had happened, Brazilians jumped in to say they were lying. The row exposes the underlying tension that has been building up in Pacaraima.

Where else are Venezuelans heading?

Other countries in the region including Colombia, Ecuador and Peru say they are struggling to deal with the influx of Venezuelan migrants.

Hundreds of thousands have made the journey into Colombia and Ecuador and many are heading further south for Peru or Chile.

On Saturday, Ecuador introduced new entry restrictions that left hundreds of migrants stranded on the Colombian side of the border.

From Saturday, only Venezuelans with valid passports were allowed to cross from Colombia in Ecuador

Amid the confusion, some desperate Venezuelans defied the new rules and entered via unguarded crossings but correspondents say they now face fines for having accessed the country illegally.

Over the past three years about 3,000 Venezuelans have entered Colombia every day and the country has granted temporary residence to more than 800,000.

Peru says that last week alone, 20,000 Venezuelans entered the country.

What's happening with the currency?

The International Monetary Fund had predicted that inflation in Venezuela could reach one million per cent this year. According to a recent study by the opposition-controlled National Assembly, prices have been doubling every 26 days on average.

From Monday, new banknotes denominated in "sovereign bolivars" are legal tender. But as it was declared a public holiday, attention is now focused on how shops and banks react when the drastic measures come into effect on Tuesday.

The move is effectively a redenomination. President Nicolás Maduro cut five zeros off the old currency - the "strong bolívar" - and gave it its new name.

Eight new banknotes and two new coins are being put into circulation. The new notes will have a value of 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 sovereign bolivars.

Most old bolivar notes will continue to circulate "for a time", Venezuelan Central Bank President Calixto Ortega announced. Only the lowest current notes, worth less than 1,000 strong bolivars, will be phased out straight away.

Will the new currency stop inflation?

The government hopes that its new economic plan will not only curb the country's hyperinflation but also put an end to the "economic war" which it says has been waged against it by "imperialist forces".

How to get by in Venezuela, when money is in short supply

It says the introduction of the new currency is accompanied by key measures which will help Venezuela's battered economy recover. Among them are:

Raising the minimum wage to 34 times its previous level from 1 September

Anchoring the sovereign bolivar to the petro, a virtual currency the government says is linked to Venezuela's oil reserves

Curbing Venezuela's generous fuel subsidies for those not in possession of a "Fatherland ID"

Raising VAT by 4% to 16%

But economists have been warning that the new measures do not address the root causes of inflation in Venezuela and that the printing of new notes could exacerbate inflation rather than curb it.

They say the rise in the minimum wage will only drive inflation up faster. Some analysts estimate that the benefits of the new currency could be wiped out by hyperinflation "within months".

- Published14 August 2018

- Published21 June 2018