Brazil elections: Why are there so many murders?

- Published

As Brazilians vote for a new president, senators and deputies on Sunday, one issue in particular might determine their choice: violent crime.

Two recent surveys strongly suggest increasing concern among Brazilians about rising levels of violence.

Candidates across the political spectrum have promised in their campaigns to address the issue.

Far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro, who's leading in the polls, wants to bolster police forces, but also to relax gun-control laws.

"Safety is our priority! It is urgent! People need jobs, they want education, but it's no use if they continue to be robbed on the way to their jobs; it's no use if drug trafficking remains at the doors of schools," he tweeted in September.

Left-wing candidate Fernando Haddad described the challenge, external Brazil faces from the drugs trade. "We're deluding people that we're fighting something. We're not fighting anything. We're losing the war," he said.

Environmentalist and candidate Marina Silva has highlighted violence against women - in 2017, Brazil registered more than 60,000 cases of rape, but experts say the true figure could be higher.

Reality Check investigates the scale of the problem.

There were more than 60,000 killings in the country in 2017, according to a study by the Brazilian Public Security Forum, which collects and analyses crime data from state and federal government. This figure includes killings linked to police interventions.

The national rate was up to 30.8 killings per 100,000 people last year.

Data from the government-affiliated IPEA, external in 2016 reveals that most of the victims were male and about half were aged between 15 and 29.

The rate in 2016 among black Brazilians was more than double that of other racial groups.

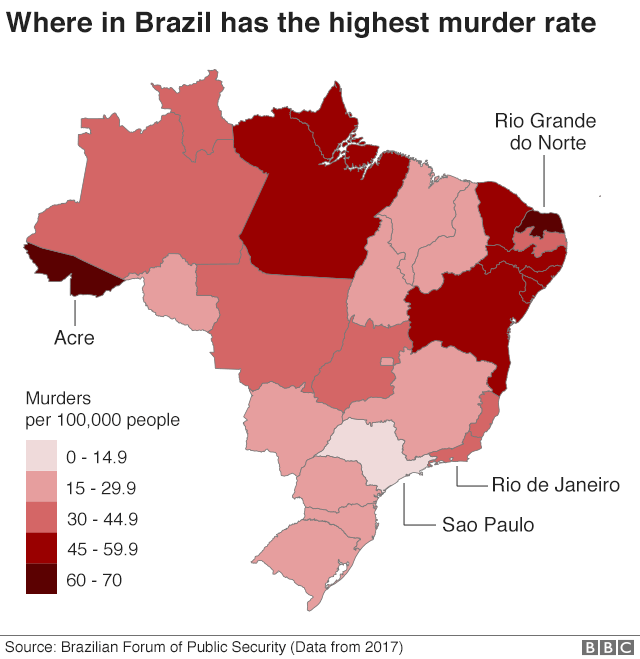

Of the five states with the highest murder rate, four are in the north-east of Brazil.

Rio Grande do Norte earned the unenviable title of having the country's highest murder rate - 68 per 100,000 people.

Over the past decade the murder rate in that state has soared by more than 250%, according to the IPEA.

The state of Acre on the north-western border with Peru had the second highest murder rate.

Each of the top five states recorded an increase compared with the previous year - Acre and Ceará by more than 40%.

Read more about Brazil's election:

'Crime is a choice for young males'

What has caused this explosion of violence?

The lucrative drugs trade is a major factor. Rival cartels fight for control of the routes that transport cocaine arriving from Colombia, Bolivia and Peru.

The UN has increasingly highlighted Brazil's role in the international cocaine trade - not as a producer but as a transit country.

Brazilians in the wealthier south-east of the country are increasingly becoming consumers of cocaine, and large quantities are also shipped to Europe, Africa and Asia.

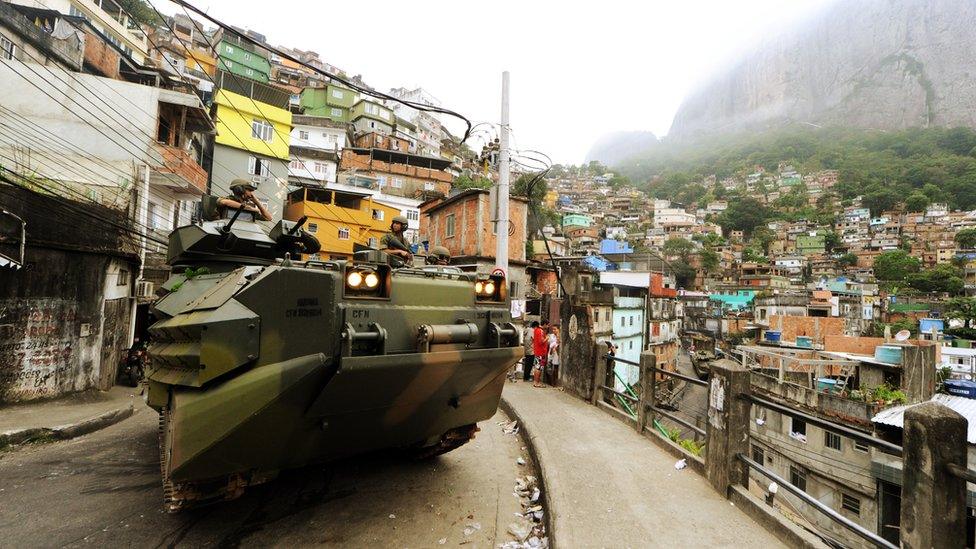

Brazilian marines entered Rio de Janeiro in 2011 to seize control of the city's largest favela

Clamping down on the drugs trade has contributed to a ballooning prison population.

Fernando Haddad, from the same left-wing party as ex-president Luiz Inácio "Lula" da Silva, said during the campaign that the prison population had pretty much doubled in 10 years. And he was about right.

It's the third highest in the world, according to World Prison Brief, external.

The number of people in Brazil's prisons per 100,000 of the population was 353 in 2016, up from 137 in 2000.

The dominating presence of gangs in prisons strengthens the ties that inmates have with crime. This is difficult to undo, says Roberta Astolfi, a crime expert at the Brazil Public Security Forum.

But the escalation of violence is also linked to multiple socio-economic factors, experts say.

"We didn't think violence would increase in the northern states," says Ms Astolfi.

Economic growth in the 2000s led to improved living standards even in the poorest parts of Brazil. But opportunities are still very limited for young people and many young people drop out of school at around 15, she says.

"Crime is a choice on the table for young males in the peripheries of cities," she added.

Experts also blame poorly implemented gun laws and dwindling police resources.

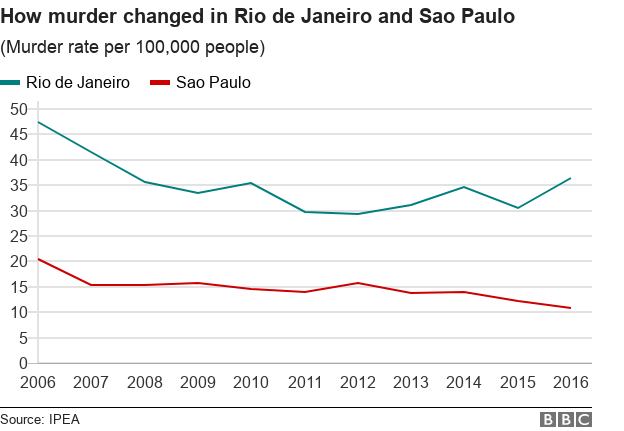

However, there has been a steady decline in murders in Brazil's most populous state of São Paulo, which includes the city of the same name with 13 million inhabitants. The level of crime is still high though - there were more than 4,000 killings in the state in 2017.

In Rio de Janeiro, murders are down compared with the highs of the late 1990s but the state still recorded one of the highest murder counts. Police struggle to control parts of the city, say experts, especially the poorest districts of the city known as favelas.

"Organised criminal groups such as the Red Command and the Third Command increasingly challenge the authorities and are themselves in a territorial conflict for control of favelas," says Antonio Sampaio, a conflict and security researcher at the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS).

Police interventions

The role of the police has featured heavily in pre-election campaigns and debates.

Mr Bolsonaro wants tougher police tactics against urban crime and drug-trafficking.

Other candidates suggest changing the way different branches of law enforcement handle investigations into organised crime.

There are an increasing number of deaths linked to police interventions, both military and civil branches. The numbers went up from 2,212 in 2013 to 5,159 in 2017, according to the Brazil Public Security Forum.

Last year, 367 police officers were killed, a decrease on the previous year. The majority of deaths occurred among off-duty police officers.

Given the importance placed on this issue in a country with one of the highest murder rates in the world, Brazil's next president will be judged on the success of policies implemented to tackle violent crime.