'Stolen friend': Rapa Nui seek return of moai statue

- Published

Hoa Hakananai'a was removed from Rapa Nui in the 19th Century

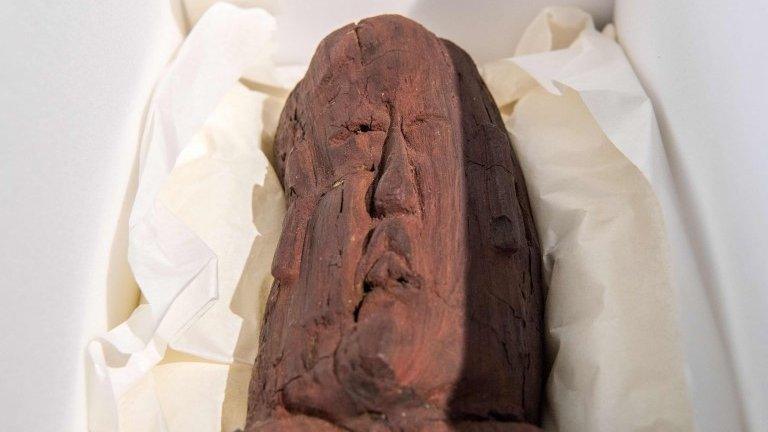

Prominent among the eclectic hoard of treasures in London's British Museum is the imposing figure of Hoa Hakananai'a, a four-tonne basalt statue from the Chilean Pacific territory of Rapa Nui - named Easter Island by European explorers.

The statues, known as moai, were carved by the island's indigenous Rapa Nui people to embody the spirit of a prominent ancestor, with each considered to be the person's living incarnation.

The moai are one of the main attractions for visitors but to locals they have spiritual significance

"The British taking the moai from our island is like me going into your house and taking your grandfather to display in my living room," says Anakena Manutomatoma, who is a native of the island and serves on Rapa Nui's development commission.

"For us, the repatriation of Hoa Hakananai'a is an absolute priority."

Long way from home

The statue, along with a second, smaller moai known as Hava, were given as gifts to Queen Victoria in 1869 by the captain of HMS Topaze, Commodore Richard Powell.

You may also be interested in:

His crew excavated Hoa Hakananai'a from a cliff top near the Rano Kau crater in November 1868, and the Queen donated the two statues to the British Museum.

It has been on display 8,500 miles (13,700km) from its spiritual home ever since.

Alongside its clear cultural and spiritual importance, Hoa Hakananai'a is a particularly fine example of the statues that see thousands of tourists visit Rapa Nui each year.

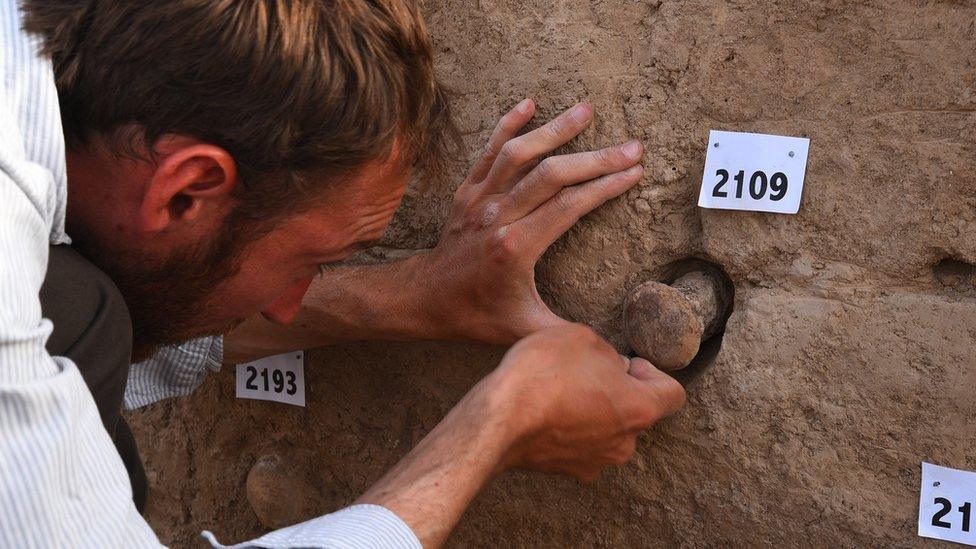

"In some ways the statue is unique because it is made from a very hard basalt lava rock, unlike the majority of statues on Rapa Nui. As such, it is unusually well-preserved and its features are pristine," says archaeologist Mike Pitts, who spent several nights at the museum in 2012 conducting a detailed scan of Hoa Hakananai'a.

"It also has a unique collection of petroglyphs on its back that almost certainly were not part of the original statue, so you have a second layer of history embodied in the stone."

Calls for repatriation

There has been a recent awakening on the island with regard to repatriating the moai, which under Chilean law are considered to be part of the land.

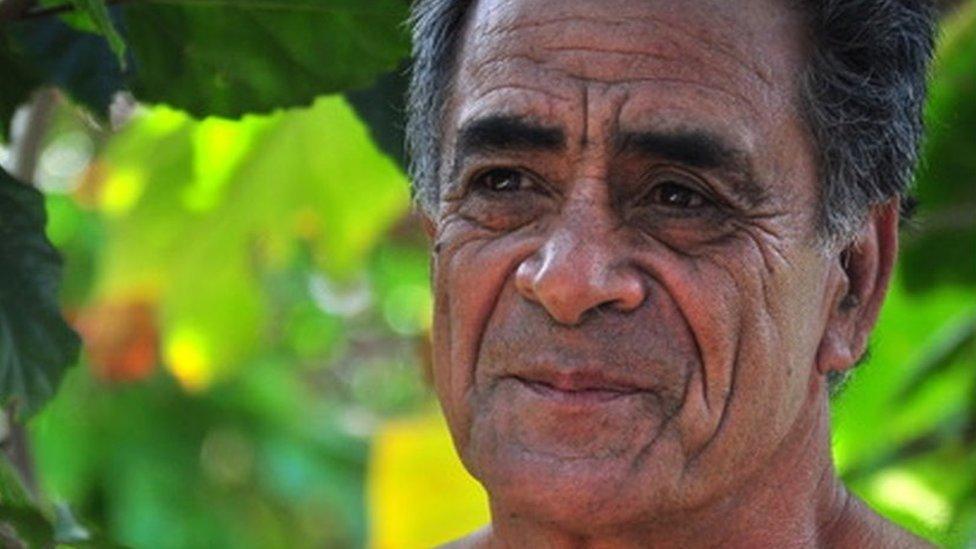

Sculptor Benedicto Tuki, a Rapa Nui native who has dedicated his life to promoting and preserving the island's indigenous culture, attributes the newfound interest in bringing the moai home to a generational shift.

Benedicto Tuki has devoted his life to preserving the island's indigenous culture

"Perhaps in the past we did not attach so much importance to Hoa Hakananai'a and his brothers, but nowadays people on the island are starting to realise just how much of our heritage there is around the world and starting to ask why our ancestors are in foreign museums."

In order to facilitate the return of the Hoa Hakananai'a, a name often translated as "lost" or "stolen friend", Tuki has offered to make an exact replica to take the statue's place in the British Museum, free of charge.

"Perhaps it won't possess the same ancestral spirit, but it will look identical," the sculptor says. "My only wish is for him to return home; for me this is worth far more than any amount of money. As long as I live, I will fight to see our ancestors returned to the island."

Asking to be heard

Tuki made the offer after the mayor of Rapa Nui, Pedro Edmunds, sent a letter to the British Museum in August requesting the return of the two statues.

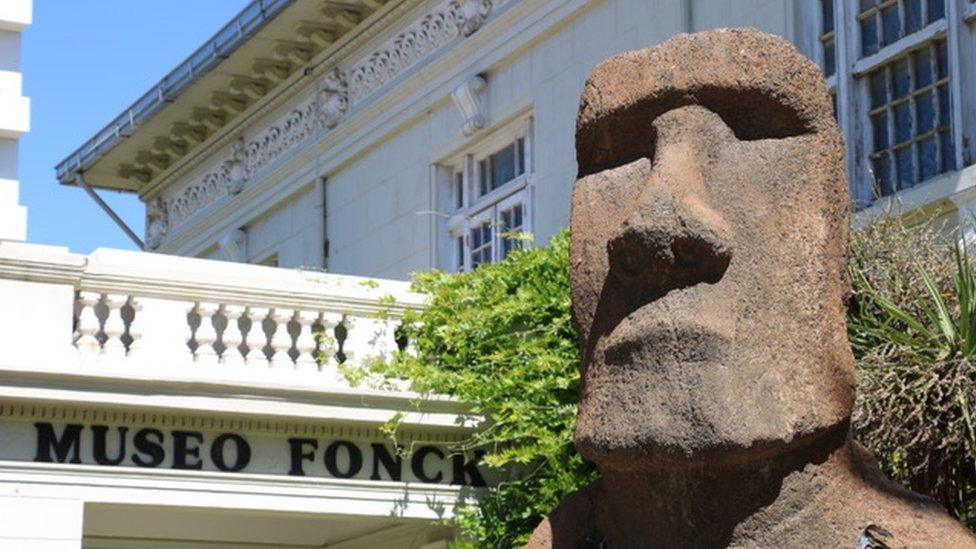

There is also a moai outside the archaeology museum of the Chilean city of Viña del Mar

In response, the museum invited a delegation from Rapa Nui to visit the moai and discuss the request.

A group including Ms Manutomatoma will arrive in London on 19 November to propose to the museum's directorate to have Hoa Hakananai'a returned to the island in exchange for Tuki's replica.

Chile's Minister for National Property Felipe Ward, who is leading the delegation, says he is optimistic. "The strong understanding and mutual respect between Chile and the UK can help in this instance."

Anakena Manutomatoma (first from left) and Felipe Ward (third from right) will form part of the delegation

"We are not demanding anything as yet, just asking to be heard. We believe that when this happens, the museum and its authorities will understand the importance of the moai as the soul of the island," he says.

For Tuki, bringing Hoa Hakananai'a back to Rapa Nui is just a first step. Eventually, he would like to see all moai which were removed from the island returned, starting with those that are currently on the Chilean mainland.

"In order for Chile to show that it is serious about supporting our cause, we need to have the moai on the Chilean mainland returned to the island," he says.

Talks are currently under way to return a moai from the Chilean city of La Serena but there are also moai in Viña del Mar and also as far afield as the US, New Zealand, France and Belgium.

Anakena Manutomatoma says that while she, too, dreams of bringing all of her ancestors home to Rapa Nui, her gaze is firmly on Hoa Hakananai'a.

"We have mourned him for too long. It is time to stop crying and take action to bring him home."

- Published9 August 2018

- Published4 July 2018

- Published21 March 2018

- Published1 July 2017

- Published2 June 2017

- Published21 March 2015