How dangerous is Mexico?

- Published

In January, 10 indigenous musicians were ambushed in western Mexico

Deadly attacks by gunmen on targets including an amusement arcade and a group of indigenous musicians returning from a concert have shone a spotlight on the violence which has been plaguing Mexico for years. The murder rate has been on the rise for the past four years. But how widespread is the violence and how risky is it to live or travel to Mexico?

How bad is the murder rate?

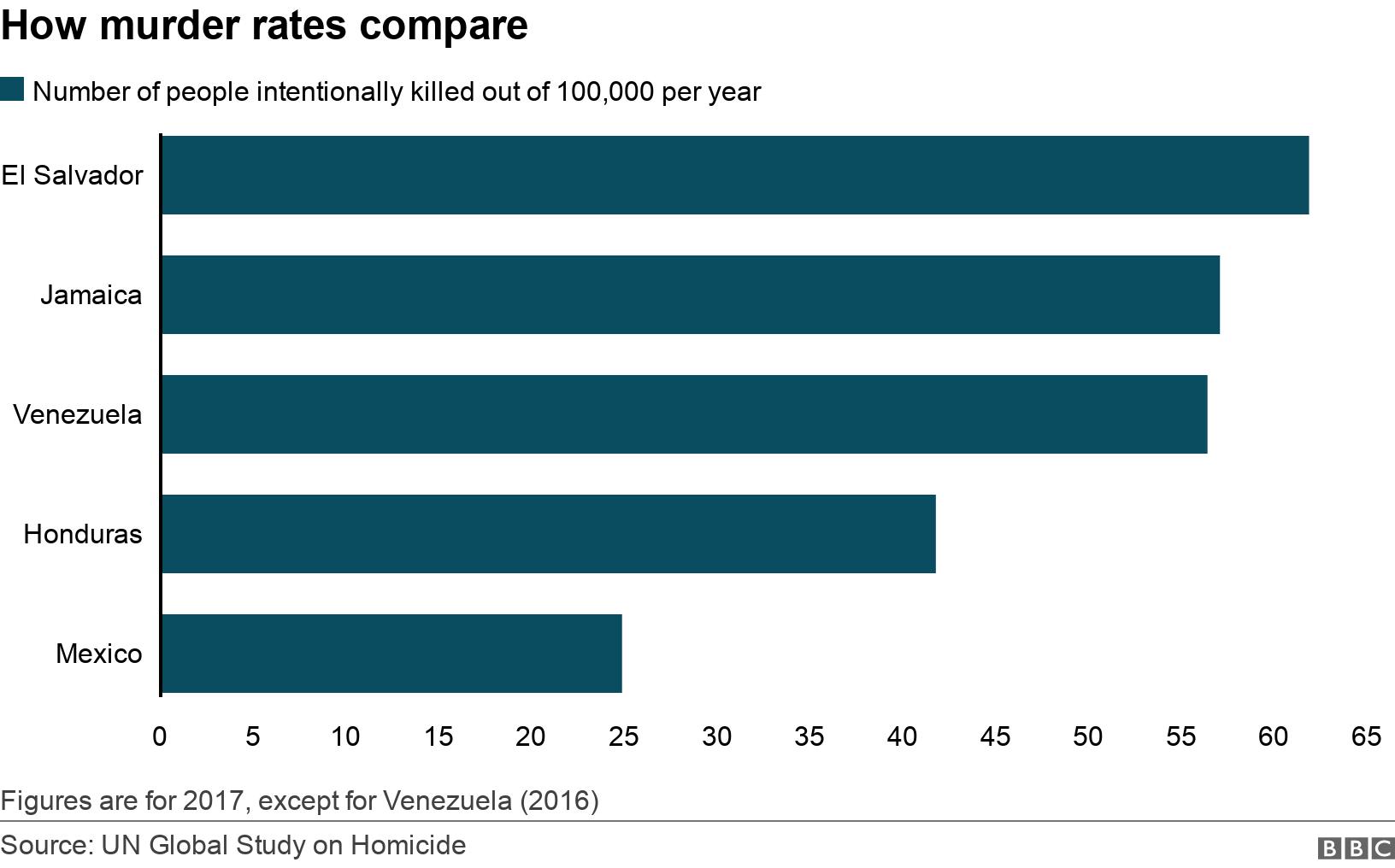

Mexico's homicide rate has been rising every year since 2014 but it remains well below those of other countries worldwide.

Globally, it ranks at number 19 in the list of countries with the highest rate of intentional homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, according to the most recent figures gathered by the United Nations.

At 24.8, Mexico's rate was much lower than that of the top-ranking country worldwide, El Salvador, where 61.8 people out of 100,000 died from violent crime in 2017.

Has it been getting worse?

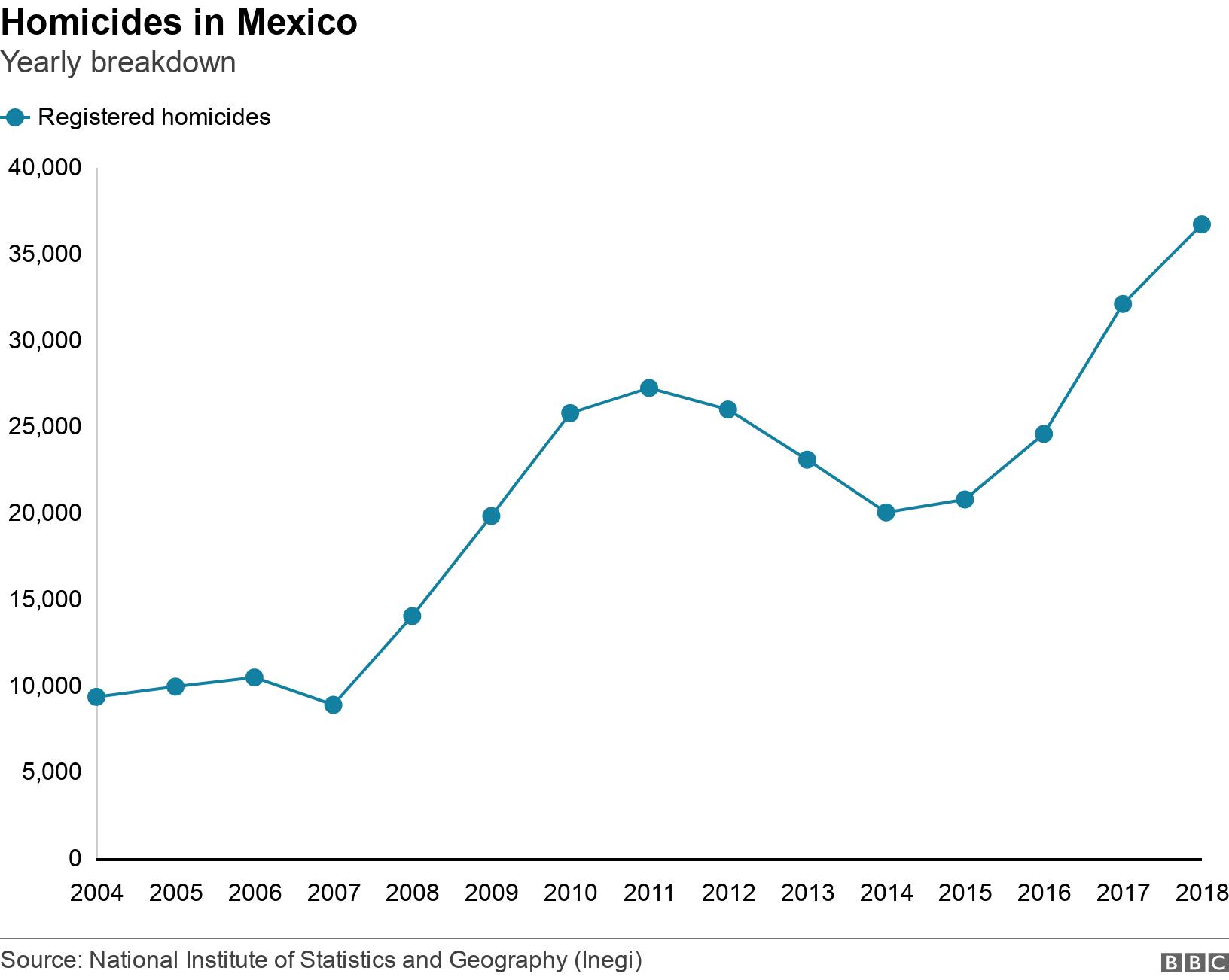

Yes, the number of homicides in Mexico has been on the rise since 2014. In 2018 the number of people killed was more than four times that in 2007.

Preliminary figures released by Mexico's National Institute for Statistics for the first six months of 2019 suggest a drop of 3.2% in homicides compared to the same period the previous year.

But figures compiled by another official body, the National System for Public Security, suggest that in the whole of 2019 the number of murders was higher than in 2018.

The two bodies use different methods of gathering information, with the National Institute for Statistic using forensic reports which include deaths suspected to be homicides and the National System for Public Security using only those ruled to have been homicides after the investigation is concluded.

Mexican governments have long argued that the majority of the victims have ties to criminal gangs or have somehow become "mixed up" in their illegal business. But with scenes such as those in the city of Culiacán in October, where residents had to take cover as a convoy of heavily armed cartel trucks rolled into the city, being shown on TV, more and more people are questioning whether they may be in danger.

Which are most dangerous areas?

The states with the highest homicide rates are: the tiny western state of Colima in the west, followed by Baja California, Chihuahua in the north and Guerrero, according to figures released by the National Institute for Statistics, external.

Much of the violence in concentrated in crime hotspots where gangs are either active or fighting over territory. There are many areas which have been relatively untouched by violence. In the popular tourist destination of Yucatán, the homicide rate is only 3 per 100,000 people, lower than that of Thailand.

The states of Aguascalientes, Campeche and Coahuila also are well below the national average and have homicide rates similar to that of Uruguay.

What is at the root of the violence?

Mexico's location on the southern border of the US means that for decades it has been home to powerful criminal groups smuggling cocaine, heroine, marijuana and methamphetamines north to the United States, the world's largest market for illicit drugs.

The deployment of soldiers has failed to quell the violence

These groups do not just deal in drugs but also engage in extortion, money laundering, human trafficking, people smuggling and contract killings. Some are transnational enterprises which operate as far south as Argentina and have off-shoots in Europe.

They often bribe or infiltrate the security forces and pay off or threaten politicians so that they turn a blind eye to their illegal enterprises.

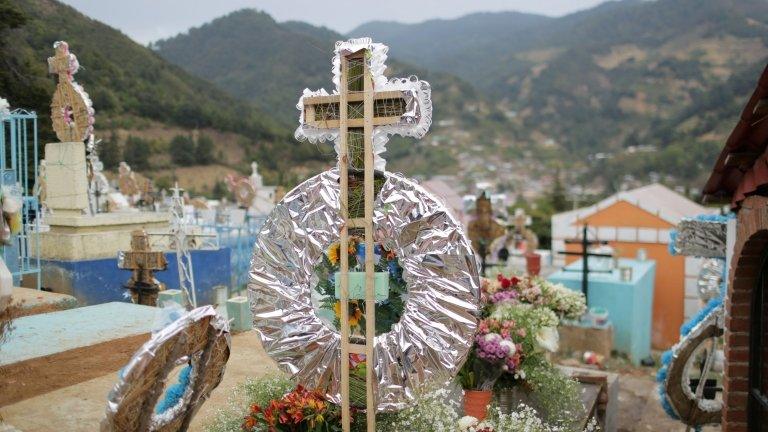

In some rural communities, residents have created their own police force because they do not trust the official one

Rival gangs battle for territory and over control of lucrative smuggling routes and often use gruesome tactics such as hanging bodies from bridges and decapitations to spread terror and fear.

While some of the top leaders of the powerful cartels have been arrested or killed in recent years, the result has not been a drop in crime, as officials had hoped. Instead, the vacuum left behind has led to further battles between rival gangs and warring pretenders to the vacant leadership positions.

What is the government doing?

In December 2006, then-President Felipe Calderón launched a "war on drugs", deploying more than 50,000 soldiers and federal police officers. In the six years of his presidency, the official figure of people killed in drug-related violence was 60,000. Many estimate the figure may have been much higher.

His successor in office, Enrique Peña Nieto, at first said that he would tackle the roots of the violence but his policy closely resembled that of Mr Calderón, going after the heads of the most powerful criminal organisations.

His biggest coup was the capture of Sinaloa cartel leader Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán in 2016. But even following his extradition to the US, Guzmán's Sinaloa cartel remains a powerful force.

In October, one of El Chapo's sons, Ovidio Guzmán López, was freed on the orders of the Mexican government after Sinaloa cartel gunmen flooded the city of Culiacán and surrounded security forces to press for their boss's release.

Watch clashes between Mexico's security forces and drug cartel members

Current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador ran on a promise to "achieve peace and end the war" on drugs. He defended his government's decision to free Ovidio Guzmán López by arguing that the move had prevented a bloodbath.

President López Obrador's strategy to create a National Guard has so far not yielded tangible results. Few have signed up for the new force and those who have have been deployed to the southern border to deal with a huge influx of US-bound migrants.

His critics argue that the president's lack of a defined strategy to combat criminal groups has led to a further increase in violence. They say that while the release of El Chapo's son may have saved lives on the day, it set a dangerous precedent and will lead to cartels further flexing their muscles.

- Published4 February 2020

- Published3 February 2020

- Published30 January 2020

- Published29 January 2020

- Published24 January 2020

- Published18 January 2020

- Published7 January 2020

- Published5 November 2019