Mexico ambush: How a US Mormon family ended up dead

- Published

Nine members of a Mormon community in northern Mexico died in an ambush by gunmen while travelling from their home on the La Mora ranch to a nearby settlement. But how did the victims, all US-Mexican citizens, come to be in the line of fire?

The dirt road that runs through the Sierra Madre mountains is no place for children to die. Remote, rocky and cold, it is controlled by men financed by Mexico's illegal drug trade and armed by America's guns.

It's about as hostile a stretch of road as can be found in Mexico.

The raw grief of the extended LeBarón family is worsened by the upsetting details of how the infants met their deaths on that stony track - trapped in a burning, bullet-riddled car.

Eight-month-old twins, Titus and Tiana, died alongside their two siblings, Howard Jr, 12, and Krystal, 10, and their mother, 30-year-old Rhonita Miller.

Their grandfather filmed the aftermath of the cartel ambush with his mobile phone "for the record" as he put it, his voice cracking. The disturbing footage showed a blackened and still-smouldering vehicle, the charred human remains clearly visible inside.

Further up the road, two more cars, also full of mothers and young children, were attacked an hour later. In total, nine people were killed. Most were not yet teenagers, several were still toddlers.

Dawna Ray Langford and her sons Trevor, 11, and Rogan, two, were killed in one car while Christina Langford Johnson, 31, was killed in another. Her seven-month-old baby, Faith Langford, survived the attack. She was found on the floor of the vehicle in her baby seat.

Perhaps the only solace for this tight-knit Mormon community exists in the knowledge that the children who died were with their mothers - a family united to their untimely, violent end.

The funeral of Dawna Langford and her sons took place this week

Yet the story of how the LeBarón clan came to live in such a dangerous corner of northern Mexico is not one born of unity but of division, stretching back decades.

The Mormon fundamentalists started to move to Mexico from around 1890 when they split with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). Primarily, they parted ways over the question of polygamy, which the breakaway Mormon groups continued to practise while the mainstream church, based in Utah, prohibited to comply with US law.

Polygamy was illegal in Mexico too - but there was an understanding that the authorities would "look the other way about their marriage practices", explains Dr Cristina Rosetti, a scholar of Mormon fundamentalism based in Salt Lake City.

"The families who went there were not 'fringe families' or 'bad Mormons'," she says. "These were leaders of the church; they weren't peripheral people. Big names went down there."

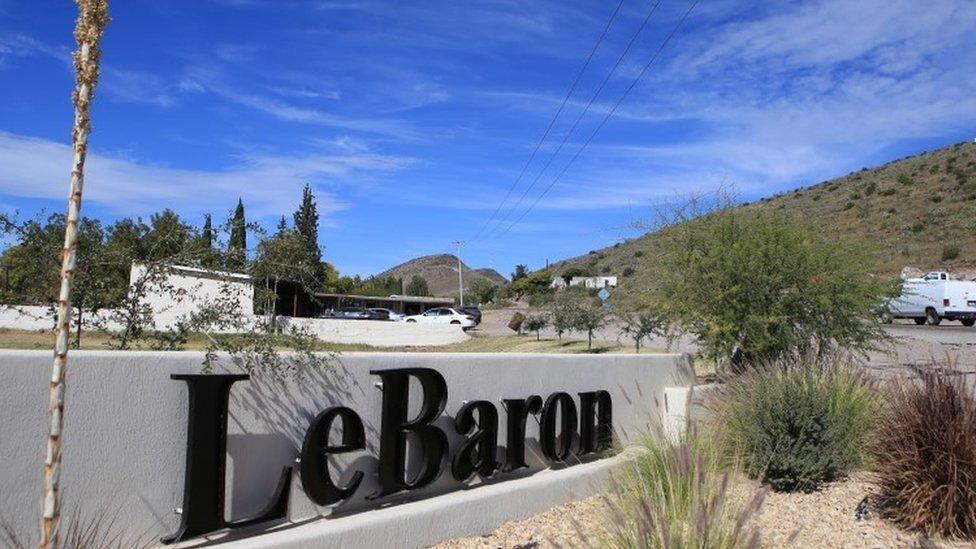

The LeBarón group's patriarch, Alma "Dayer" LeBarón, established Colonia LeBarón in Chihuahua in the 1920s.

In time, the Mormon community south of the border grew in number and wealth.

They purchased land in the states of Sonora and Chihuahua and set up ranches and other colonias. They thrived as pecan farmers, grew wheat, planted apple and pomegranate orchards and produced honey to sell at farmers' markets. Although many returned to the southern United States after the Mexican Revolution, by the 1950s the Mormon enclaves had populations in the high hundreds or low thousands.

After Alma LeBarón died, the offshoot was led by his son Joel. In essence, it was the LeBarón Church, an independent fundamentalist Mormon denomination of which today there are several branches.

It was at this stage that the LeBarón family name took on its notoriety. Joel's brother, Ervil LeBarón, was the second-in-command until they fell out over the direction of the church. An unhinged and dangerous cult leader who had 13 wives and scores of children, Ervil then split and created a separate sect. In 1972, he ordered his brother's murder and it is believed Ervil's followers killed dozens of others on his command, including one of his wives and two of his children. He died in prison in 1981.

Yet the victims of the massacre in Sonora had nothing to do with Ervil's church. There is an important distinction to be drawn, explains Dr Rosetti, between surnames and religious affiliation.

"Independent Mormons have been marrying LeBaróns, and vice versa, for generations," she clarified on Twitter. "There are three distinct Churches that fall under 'LeBarónism'."

The majority of Mormons living in Mexico are members of the Church of Latter-Day Saints (LDS), but those in La Mora are mostly independent, Dr Rosetti said.

In recent years, they have lived a broadly peaceful existence, free from US or Mexican government interference. Of the US, but not entirely American; in Mexico, yet not fully Mexican either, the extremist Mormon group began to soften at the edges a little too.

Their adherence to polygamy has slowly been phased out, although some still practise it. Most have dual citizenship and travel back and forth to the US freely and frequently.

"When you say Mormon, it is a very big umbrella term that covers lots of families," says Dr Cristina Rosetti. "The fundamentalists are a big umbrella, and so are the LeBaróns."

Yet it seems violence has again been associated with the LeBarón name.

Relatives visited the scene of the shooting to mourn the dead

It isn't easy to remain shielded from the drug war when you live in cartel-controlled regions of Mexico. The drug-related violence began to worsen from late 2005, and subsequently grew in intensity and ferocity during the military deployment ordered by former-President Felipe Calderón.

His successor, Enrique Peña Nieto, oversaw the bloodiest term in office in modern memory as the cartels first expanded, then splintered and grew new tentacles.

In 2009, the Mormons in the northern states of Mexico were warned in the clearest possible terms that they inhabited "tierra sin ley", a lawless land. One of their number, Benjamin LeBarón - great-grandson of the group's founder, Alma - had spoken out about organised crime. He criticised the extortion and intimidation being exerted on local farmers and created a group called SOS Chihuahua urging towns to denounce the abuses to the authorities.

In July of that year, Benjamin was dragged from his family home by gunmen with his brother-in-law, Luis Widmar, who had tried to intervene. The next day, their dead bodies appeared on the outskirts of town having been brutally beaten and with signs of torture.

The drug cartel's message to LeBarón family was clear: don't meddle with us; don't meddle with our business interests or the smooth operation of our drug routes north. Don't talk to the police or draw attention to things that are happening in these states. To defy such a warning will cost you your life.

'It's their livelihood'

It is a little over 10 years ago since those armed men killed Benjamin LeBarón. During that decade, it seems his relatives have established a sort of uneasy peace with the local cartel in Sonora, a group called Los Salazar, which is a faction of the powerful Sinaloa Cartel of the jailed drug lord, El Chapo Guzmán.

"It's not like they can uproot an entire community," says Anna LeBarón, Ervil's daughter, who wrote a book about life in her father's sect called The Polygamist's Daughter.

Anna says she has seen the calls for the Mormons to return to the US but points out that "it isn't that simple." The Mormon community pre-dates the drug cartels in Sonora and, even though they now live side-by-side to some very violent people, it isn't realistic to expect them to simply leave. They are "very integrated" into the local area, she says.

"These kinds of events give people reason to consider their options. But it's an entire community. It's their livelihood."

In fact, following the massacre, some Mormons have described how the drug gangs are simply an accepted part of daily life in Sonora. They would nod as they passed by cartel gunmen, might know their names, would stop at their checkpoints and show them they were only transporting agricultural produce in their pick-up trucks.

Almost from the moment that the news broke of the attacks, the Mexican government has claimed that the killings were a case of mistaken identity. An armed group called La Linea supposedly carried out the ambush and confused the SUVs of women and children with a convoy of Los Salazar, their Sonora-based rivals, the authorities say.

La Línea, meaning The Line, was originally made up of ex-municipal police officers from Ciudad Juarez, says Mexican security analyst, Carlos Rodriguez Ulloa.

"They marked out the line, that's to say, they enforced order" for the Juárez Cartel, he explains. Eventually the Juarez Cartel limited its operations to running the drug routes or "plazas" in the city from which it takes its name. Its enforcers, La Linea, then filled the void they left in the state, he says.

"As a well-positioned actor, La Línea assumed the roles and responsibilities (of the Juárez Cartel), and now has control of the routes and 'plazas'. It grew to a point that it consumed most of the Juárez Cartel and has today become the principal trafficker in Chihuahua."

'Unimaginable brutality'

Were the murders of the Mormon women and children simply an accident in the wider story of La Línea versus Los Salazar? Certainly some representatives of the LeBarón family don't think so. They believe their loved ones were deliberately targeted:

"The question of whether there was confusion and crossfire is completely false," said Julian LeBarón from inside the Mormon settlement of La Mora, shortly before the funerals of his slain relatives. "These criminals who have no shame opened fire on women and children with premeditation and with unimaginable brutality. I don't know what kind of animals these people are."

It is a murky picture still. Mr LeBarón says one of the mothers, Christina Langford, had left the car with her hands raised, pleading for the gunmen to stop yet they murdered her anyway. Evidence, perhaps, that La Línea were targeting the Mormons - either for having a relationship with their rivals, Los Salazar, or for having the audacity to speak out on guns.

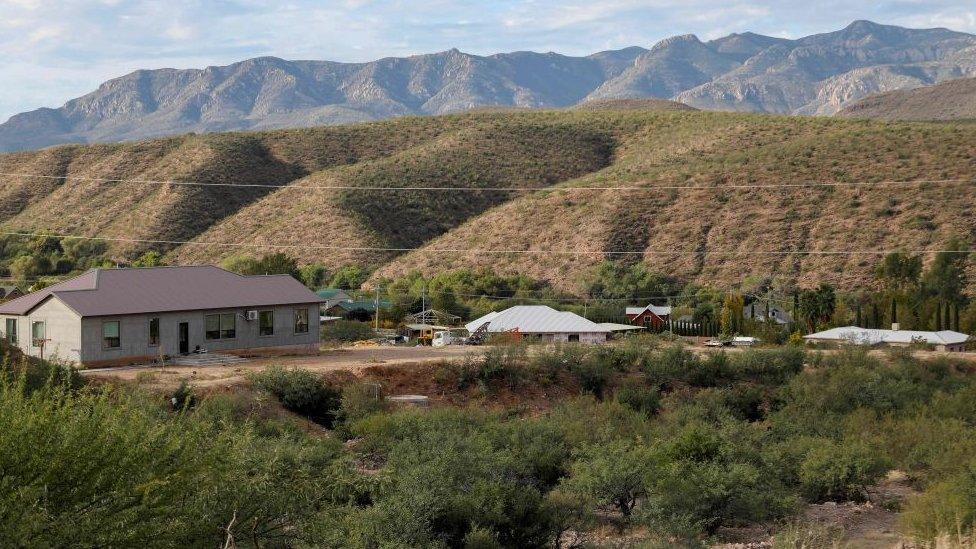

The La Mora ranch, where the victims lived

Recently the family had become more vocal again in their opposition to the cartels, especially in calling for action on the illegal traffic in assault weapons and high-velocity arms from the United States. Whether their activism was enough to provoke such cold-blooded slaughter of their children is hard to say.

Meanwhile, the Mexican government argues the gunmen allowed some of the children to escape - evidence, they say, of the cartel's realisation that a mistake had been made. The Mexican government would doubtless prefer this to be the case.

As the victims were US citizens, the murders have an international dimension which has increased the pressure on President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Until now, he has tried to avoid becoming embroiled in an ever-escalating war with the drug cartels. "Hugs, not guns", he famously said on the campaign trail. An honourable sentiment, no doubt, yet many people in Mexico - and in Washington too - feel it is naïve and that his approach of non-violence isn't working any more effectively than the military-led strategy of his predecessors.

In the end, perhaps the question of whether the attack on the Mormon community was an error or deliberate isn't the point. Much like the murder of Benjamin LeBarón 10 years ago, the perpetrators' desired effect was to sow fear, to terrorise people in the region.

As the tiny, hand-hewn, wooden coffins are lowered into the rocky ground, the killers certainly appear to have achieved that aim.

Additional reporting by Lauren Turner

- Published7 November 2019

- Published6 November 2019

- Published18 February 2020

- Published24 October 2019