Chile protests: President Piñera condemns police 'abuses'

- Published

Police have been accused of aiming at protesters' eyes

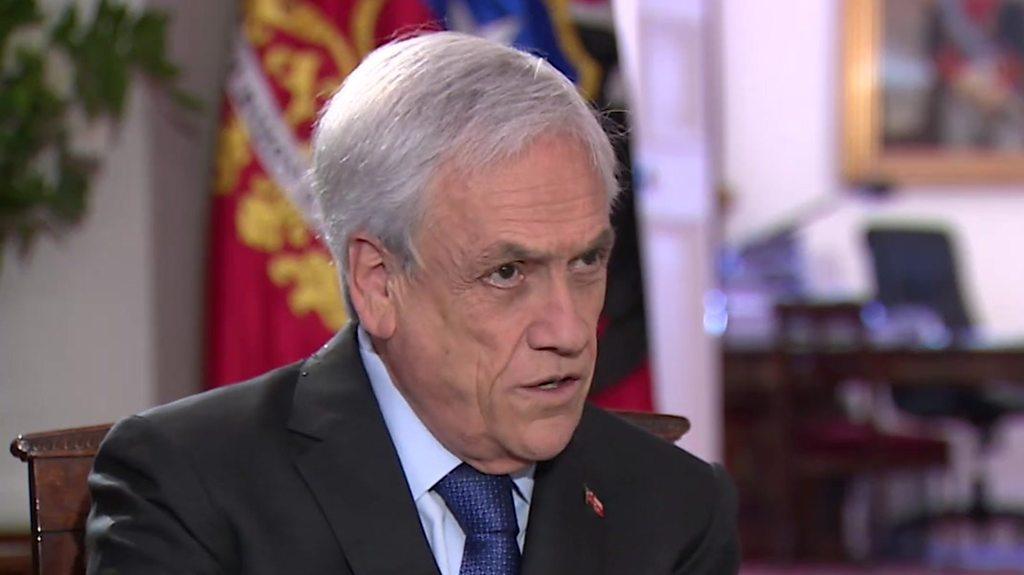

Chile's President Sebastián Piñera has acknowledged that the police committed "abuses" when dealing with protests which have been rocking the country for the past month.

He said "there was excessive use of force" in the police response to mass protests against inequality.

There would be "no impunity" for those who committed excesses and abuses, he added.

Twenty-two people have been killed and more than 2,300 injured.

In a televised speech, President Piñera acknowledged for the first time since the protests began that "abuses and crimes were committed, and the rights of all were not respected".

But he also criticised protesters who had engaged in acts of violence such as arson and attacks on the security forces, saying there would be no impunity either for them "nor for those [security agents] who committed excesses and abuses".

President Piñera said there would be "no impunity"

He said "in the last four weeks, Chile has changed" and welcomed an agreement reached last week for a referendum to be held in which Chileans will be asked if they want a new constitution to replace the one imposed during the military rule of Gen Augusto Pinochet.

Calls for a new constitution have been among the main demands of the protesters.

What are the abuses he is referring to?

Public prosecutors are investigating more than 1,000 cases of alleged abuses carried out by the security forces since the protests began. A further 1,000 allegations have been reported but have yet to be looked into by the prosecutors, the head of the body's rights division said.

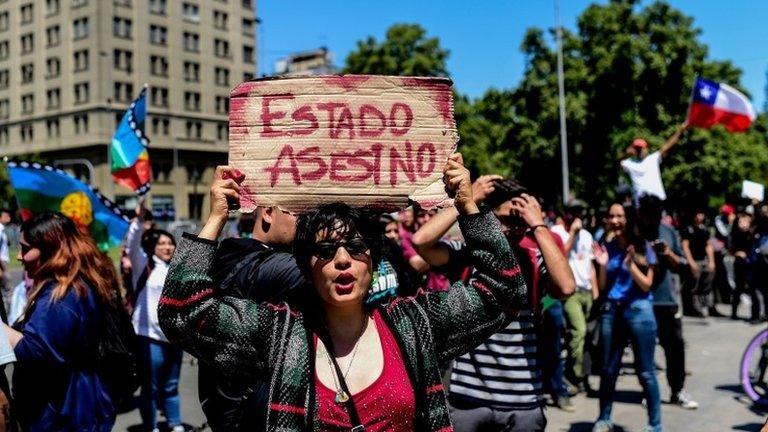

Women march in Chile, demanding justice for recent injuries and deaths of protesters

The allegations range from "cruel treatment", including torture, to sexual abuse. More than 200 people have also sustained eye injuries from rubber bullets and tear gas cylinders with many alleging the security forces aimed at their eyes on purpose to try and blind them.

According to Chile's National Institute of Human Rights (INDH), external, 2,381 had to be taken to hospital due to injuries sustained during the protests. At least 24 people have been killed and murder charges have been pressed in five cases, the INDH says.

More than 200 protesters have sustained eye injuries

The United Nation's human rights chief, Michelle Bachelet, has sent a team to Chile to examine the allegations of abuse.

What are the protests about?

The demonstrations started originally over a rise in the fare of the metro in the capital, Santiago, but quickly spread across the country and widened into more general protests against high levels of inequality, the high price of health care and poor funding for education.

Huge rallies and demonstrations have ramped up the pressure on the government

Harsh repression by the security forces further stoked the anger of those protesting as did the response by President Piñera, who declared a state of emergency and said the country was "at war".

Mr Piñera has since struck a more conciliatory tone and on Sunday said "if the people want it, we will move toward a new constitution, the first under democracy".

The current constitution, which came into force in 1980, is seen as a hangover from the time of military rule with its trust in neoliberal economics and Catholic values.

While there have been some amendments since 1980, many Chileans think those have not gone far enough to modernise the document. They demand that the state take a more active role in providing public healthcare and education.

Under an agreement between the government and opposition parties reached on Friday, a referendum will be held in April 2020 in which Chileans will be asked whether they want a new constitution and if so, how it should be drafted.

But the announcement of the planned referendum failed to quell the protests in Santiago, where demonstrators again gathered at Plaza Italia and small groups clashed with police.

- Published15 November 2019

- Published5 November 2019

- Published30 October 2019

- Published29 October 2019

- Published27 October 2019