Chile protests: Concerns grow over human rights abuses

- Published

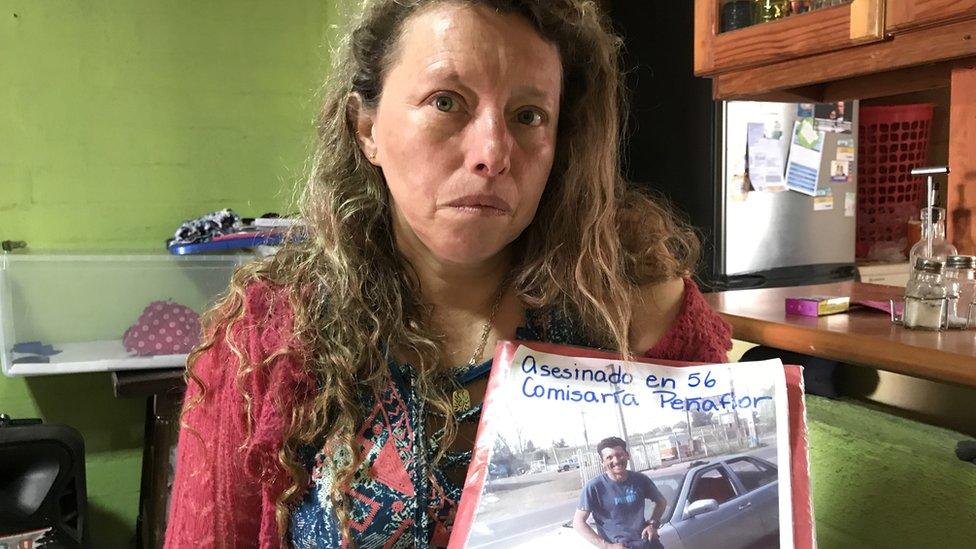

Marusella Mallea's brother was found dead in a police cell

In Marusella Mallea's living room there's a side table with a picture of her brother César on it. He's leaning against his car and has a big grin as he looks to the camera.

"Look, it was all about having a laugh," she says between tears. "He found everything funny."

In front of the photo is a candle burning. This is a makeshift shrine, a little over a week old.

A few days after Chile brought in the state of emergency to quell last month's violent protests, César went for a drive. It was after the curfew and he didn't have permission to be in the car. But Marusella says that on the outskirts of Santiago the rules weren't as rigidly obeyed as in the centre of the capital.

César went out with his daughter that evening but they parted ways around 23:00. A few hours later his family got a phone call saying he'd killed himself in a police cell.

"He had everything to live for," she says. She doesn't know when he was arrested - there are no records. The video system also failed the moment he killed himself, she says. This poor record-keeping by the police - or carabineros - makes her doubt their version of events.

Memories of dictatorship

She says these past few weeks have brought back difficult memories.

"I was two when the dictatorship started, my brother just a few months old," she says. "I still remember it as if it was yesterday. We really suffered during the coup in 1973."

"Now the wounds have reopened but this time they are deeper because we didn't lose anyone then," she adds. "Now, my brother is no longer with us. And he never had anything to do with politics or protests."

We asked to talk to the police but they declined because of the cases against them but in his first interview since the protests began, President Sebastián Piñera defended his move - and their record.

Sebastián Piñera tells the BBC's Katy Watson that he is committed to remaining as president

"We had to call the state of emergency because that was the only way to restore public order and to protect our citizens," he told the BBC. The state of emergency was brought in on 19 October after initially violent protests over a rise in metro fares.

But there's growing criticism of the authorities' use of force in response to the protests. Chile's National Institute of Human Rights says in its nine years of history, it's presented 319 complaints against carabineros for torture and cruel treatment. Of those complaints 45% were presented in the past 19 days.

"Of course there are many alleged complaints about excessive use of force or even crimes," President Piñera told BBC News. "If that took place I can guarantee you that will be investigated by our prosecutor system and it will be judged by our judicial system. There will be no impunity."

Innocent bystander

Little comfort for 15-year-old Matias Vera Valdivia, who was injured while passing through a protest. He's at the eye hospital getting treatment after he was hit six times by rubber bullets - one of them blinded him. Next week he'll have an operation in the hope he can recover his sight.

"The president's lying," he says of Mr Piñera's justification that he's protecting Chileans from the violent protesters. "There are people marching peacefully but the police are the bad ones - because of the actions of just a few people, they're implicating everyone."

Matias Vera Valdivia was blinded by a rubber bullet

Doctors here have never seen injuries like it. Enrique Morales Castillo is the president of the human rights department at Chile's Medical College. So far, there have been more than 160 eye injuries since the protests started. During a six-year period of the Israel/Palestine conflict they have just 154.

"The issue of eye loss surpasses any other period in the history of the country and even internationally, no other country has ever reported this number of cases," says Mr Morales Castillo. "The figures here surpass any other reference we have."

Use of force

A UN human rights mission is currently in the country - as is Amnesty International, collating evidence.

"The level of prevalence of use of force is so clear," says Amnesty's César Marín of the tactical campaign and crisis response team. "You turn on the TV and you can see it. Doing nothing to stop it or to reduce it speaks to you about the level of responsibility of authorities because they've not done enough to prevent the harm that the law enforcement officials are creating."

Bárbara Sepúlveda Hales of the feminist network of lawyers goes one step further. She and her team go around police stations checking on detainees and says sexual violence is a big problem. Women being stripped in front of others, rape too. She's seeing torture patterns that are repeated throughout the country.

"That's enough evidence for us to sustain that these things have been learned," she says. "It's not like some police are more abusive than the others, it's not something that occurred to them to do. It's something they have learned and probably they've been told to do."

President Piñera denies there's an institutional problem with his forces, instead arguing that any crimes are exceptions rather than the rule. But for as long as protests continue, the conduct of Chile's armed forces will be scrutinised - as will Mr Piñera's response.

At least 20 people were killed in recent protests in Chile

- Published2 November 2019

- Published30 October 2019

- Published29 October 2019