'A rich exchange': The refugees teaching languages in Brazil

- Published

Heloisa Daher's family is of Syrian and Lebanese descent but they insisted she only speak Portuguese

"Look forward, not backward," is what farmer Heloisa Daher was often told by her family of Syrian and Lebanese immigrants while growing up in Brazil.

Ms Daher remembers watching her family argue in Arabic over the dinner table, or so she thought. They wanted her to integrate into Brazilian society and so they banned her from learning Arabic. But hunger to better understand her roots lingered despite her parents insisting she grow up speaking only Portuguese.

Fifty years on, the mother of four is now enrolled in Arabic classes at Abraço Cultural (Portuguese for "cultural hug"), a refugee-led language school in São Paulo.

Ms Daher has fond memories of family dinners when her relatives would speak to each other in Arabic

After learning the basics of Arabic, she realised that what she had thought had been arguments over the dinner table had instead been friendly chatter. "It was just the guttural 'r' sound in Arabic," she says to explain her childhood misunderstanding. "It brings me joy to understand that now."

Abraço Cultural looks like any other language school, complete with scrawled whiteboards and beige school chairs. But it exclusively employs teachers from war-torn and crisis-stricken lands, including Haiti, Congo, Venezuela and Syria.

From war zone to World Cup

The school's main goal is to generate income for refugees. In five years, the school has paid over 2m reais (£370,000) in salaries to 55 refugees and vulnerable immigrants.

Ms Daher's Arabic teacher, Syrian Ali Jeratli, has been teaching here since 2015.

Ali Jeratli used to work in a hotel in Damascus before fleeing the war

When two car bombs exploded in Damascus in December 2011, the year Syria's civil war erupted, Mr Jeratli was two kilometres away on a bus.

He was on his way home from his job at the Four Seasons hotel. That night, 44 people died and 166 were injured. "My bus was late that day," Mr Jeratli recalls. "If it had left on time, I would have been at the heart of that explosion. And I might not be alive today."

The war in Syria caused the tourism industry to collapse so Mr Jeratli tried his luck in Iraq and Turkey before finally moving to Brazil. His decision was practical. The Brazilian government had adopted an open-door policy for Syrian nationals and his visa was approved in one day.

But starting over was not easy. "When I arrived here, I didn't know anyone and couldn't speak a word of Portuguese," he recalls.

You may also be interested in:

Two Syrian refugee chefs hope their businesses will make them millionaires in Brazil

After a few tough months, his fluency in English and Arabic landed him a temporary job as a translator during the Football World Cup, a dream come true for the avid football fan. It was during that time that he met people involved with Abraço Cultural, and became one of the first teachers working at the school.

Brazil has taken in just under 5,000 Syrians citizens like Mr Jeratli since 2011.

Plenty of potential

Abraço Cultural's co-founder, Daniel Morais, was volunteering at a local charity when the idea for the school struck him.

He had met refugees who were doctors and polyglots but were struggling to get a job. "I saw they had a lot of potential but didn't have any help to get started," he said.

"Syrians spoke fluent English and Arabic. Many Haitians speak up to five languages once they get to Brazil. So I thought: we need to make the most of this and start a language course."

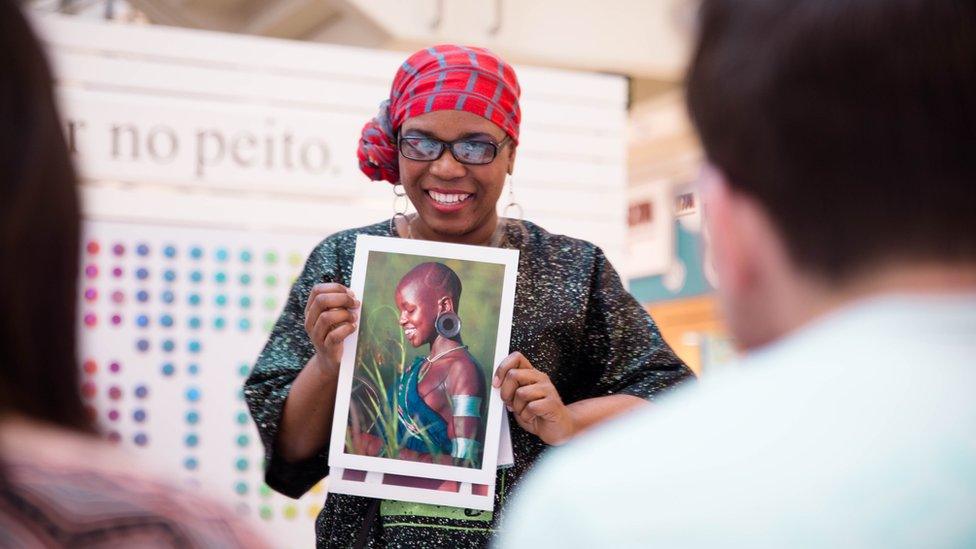

Genevieve Cherubin came to Brazil from Haiti

The non-profit school charges lower prices than other language schools and 5,200 people have signed up to its courses since its inauguration.

Today, the school receives 90% of its revenue from students, and 10% external funding for special projects. All teachers go through a two-month pedagogy programme to learn how to teach English, Spanish, French or Arabic.

"We talk about giving people opportunities to contribute. These aren't just people that need help. They have a lot to offer. It's a rich exchange," says school director Mariângela Garbelini.

Two-way street

French student Victoria Silva enjoys learning from her Congolese teacher, Joly Kayembe. "It's amazing to learn French from someone who looks like me," she explains. In Brazil, most French courses are geared towards a largely white elite.

Joly Kayembe, a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo, teaches French at Abraço Cultural

But accessible prices attract some students who do not always appreciate the school's core goal, says Ms Garbelini. "There is resistance from some students. They want to learn French to go to Paris. They don't want to learn African French," she says. "But we strive for this to be valued."

Lessons at Abraço Cultural bring in elements of history, culture, music, dance and food and Mr Jeratli has made it his mission to dispel misconceptions about his home country. "People have such a poor idea about my country. They think Syria is just bombs and desert," he says.

While continuing to spread knowledge about Syria, Mr Jeratli is also trying to make a new life for himself in Brazil. He has applied for Brazilian citizenship, which he expects to be granted soon.

But it is not just a one-way street. Through his lessons, Heloisa Daher has fallen in love with her ancestral land and plans to visit it with her children once the war is over.

- Published10 October 2019

- Published7 October 2019

- Published16 July 2019