Venezuela files legal claim with Bank of England over gold

- Published

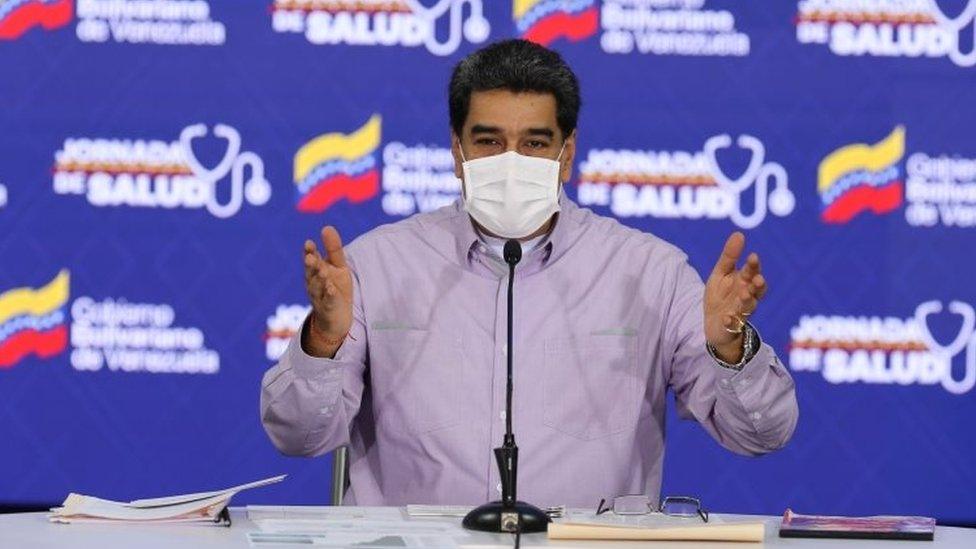

Coronavirus and the collapse of oil revenue have increased the pressure on President Maduro

Venezuela has launched legal proceedings against the Bank of England to try to force it to release €930m ($1bn; £820m) worth of Venezuelan gold.

The gold is being retained following British and US sanctions on Venezuela.

Venezuela says it wants the Bank of England to sell part of the Venezuelan gold reserves to use the funds to fight the spread of coronavirus.

It says it has agreed for the money to be sent directly to the UN to ensure it is not used for other purposes.

What's Venezuela proposing?

It is calling for the funds to be transferred to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to administer the purchase of supplies like medical equipment to fight Covid-19.

The legal wrangling comes amid fears about the ability of Venezuela's crumbling healthcare system to handle the outbreak.

The Venezuelan hospital where there's barely running water, let alone medicine

Legal documents say the bank wants the transfer made "as a matter of urgency" and it filed a legal claim to that effect in a London court on 14 May.

"With lives on the line, now is not the time to attempt to score political points," Sarosh Zaiwalla, a London-based lawyer representing Venezuela's central bank, said in a statement.

The UN told the BBC in an emailed statement only that it had been approached by the Venezuelan bank to explore such mechanisms.

The Bank of England declined to comment when asked about the case by Reuters news agency.

Why is Venezuela's gold in the UK?

The Bank of England is the second largest keeper of gold in the world, with approximately 400,000 gold bars - only the New York Federal Reserve has more.

It has one of the largest gold vaults in the world and prides itself on never having had any gold stolen in its more than 320-year history.

Central banks of a number of nations use it to store their national gold reserves and Venezuela is one of them.

Why does Venezuela want its gold now?

Despite the country's oil riches, Venezuela's economy has been in freefall for years due to a combination of government mismanagement and corruption, further exacerbated by international sanctions.

As Venezuela produces very little apart from oil, it needs to import goods from abroad, for which it needs access to foreign currency.

But with oil production a fraction of what it once was, Venezuela's foreign currency reserves have been dwindling.

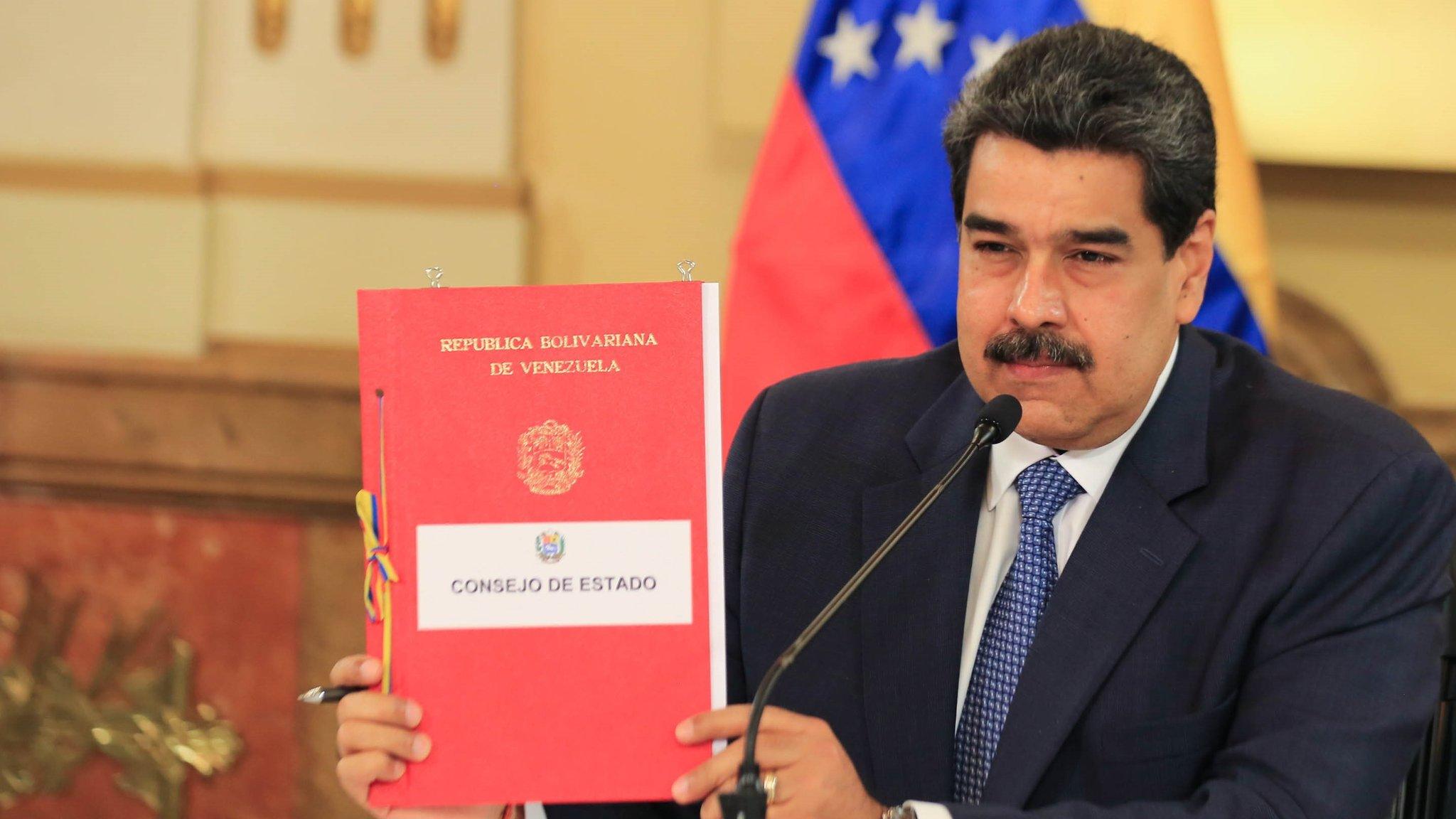

The government of President Nicolás Maduro turned to selling off some of the gold reserves kept at the central bank in Venezuela to its allies in Turkey, Russia and the United Arab Emirates.

Venezuela's gold diplomacy gamble

But the US, which does not recognise Mr Maduro's government, last year warned "bankers, brokers, traders and facilitators" not to deal in "gold, oil, or other Venezuelan commodities stolen from the Venezuelan people by the Maduro mafia".

Venezuela has reportedly continued to sell gold to its ally Iran, which is also under US sanctions, but even so its international reserves reached a 30-year low at the beginning of this year, Venezuelan Central Bank figures revealed.

It badly needs hard currency and sees the gold stored in the vaults of the Bank of England as the solution.

What's the Bank of England's stance?

Venezuela first approached the Bank of England at the end of 2018. Finance Minister Simón Zerpa and Central Bank President Calixto Ortega travelled to London to demand that Venezuela be allowed to take the gold back to Venezuela.

In January 2019, the Bank of England refused the request. All it said publicly was that it did not comment on customer relationships.

Venezuela has $1bn worth of gold stored in the Bank of England

The decision, however, came just days after Mr Maduro's rival, Juan Guaidó, had declared himself president, arguing that the 2018 election which returned Mr Maduro to power had been fraudulent.

Mr Guaidó, who was quickly recognised as the legitimate leader by more than 50 nations - including the UK and the US, asked the Bank of England not to hand the gold over to the Maduro government, arguing that it would be used for corrupt purposes.

The British minister of state for the Americas at the time, Alan Duncan, said the decision was a matter for the Bank of England and its governor, but added that "no doubt when they do so they will take into account there are now a large number of countries across the world questioning the legitimacy of Nicolás Maduro and recognising that of Juan Guaidó".

At the same time, top US officials - for whom President Maduro has long been a thorn - were also lobbying their British counterparts to cut the Maduro government off from its foreign assets.

While the Bank of England never went beyond saying that it did not comment on customer relations it is thought that international sanctions on Venezuela and regulations on preventing money laundering influenced its decision.

Venezuela's offer to have the funds transferred to the UN directly are designed to circumvent those regulations.

- Published2 April 2020

- Published31 March 2020