'You can't ask people to die': Coronavirus woes deepen Argentina's crisis

- Published

Sergio works as a cartonero - collecting litter on the streets of Buenos Aires

Sergio Sanchez, 56, has lived through enough defaults and crises to know that Argentina's economy can be a rollercoaster. Politicians come and go but economic troubles rarely go away.

"Some governments have been better than others," Sergio says. But the coronavirus pandemic has had a far bigger impact than any politician. "It doesn't care if you're good or bad, rich or poor."

Sergio's life was turned upside down when Argentina's economy crashed in 2001- the worst economic crisis in the country's history.

Argentina defaulted on a debt of $132bn - at the time, it was the largest sovereign default ever. The peso lost much of its value overnight and banks stopped allowing people to take their money out. There were protests, businesses closed, and unemployment and poverty soared.

Sergio lost his job as a driver and became a cartonero, collecting litter on the streets of Buenos Aires - "I had no option."

But that also brought change, says Sergio. People came together. They fought to make life better.

The economic collapse saw the numbers of cartoneros flourish. Sergio now heads one of the biggest cartonero co-operatives in the country.

Cartoneros also help with the city's recycling (file photo)

And three times a week he helps run a soup kitchen in the south of Buenos Aires.

With a visor and a clipboard in hand, Sergio oversees volunteers chopping up meat and pumpkin, ready for the onslaught of people in need of food.

"We started off with an average of five to six hundred people [a day]," says Sergio of his soup kitchen, which has been going for three years. "Last year it got to 1,200 and that shocked us. Now, it's anything between 3,000 and 6,000 we try to help."

Covid-19 and economic crisis

When Europe was struggling to contain coronavirus, Argentina reacted by locking down early. The tough measures introduced by President Alberto Fernández have paid off in some respects. To date, Argentina has recorded around 15,000 cases and just over 500 deaths - far lower than neighbours like Brazil.

But it's come at a huge economic cost.

Argentina has seen almost 15,000 coronavirus cases so far

"It was already pretty bad for us but with this, it's just got worse," says 21-year-old Omar, who is standing in the queue for the soup kitchen. "The economy has collapsed as far as I'm concerned."

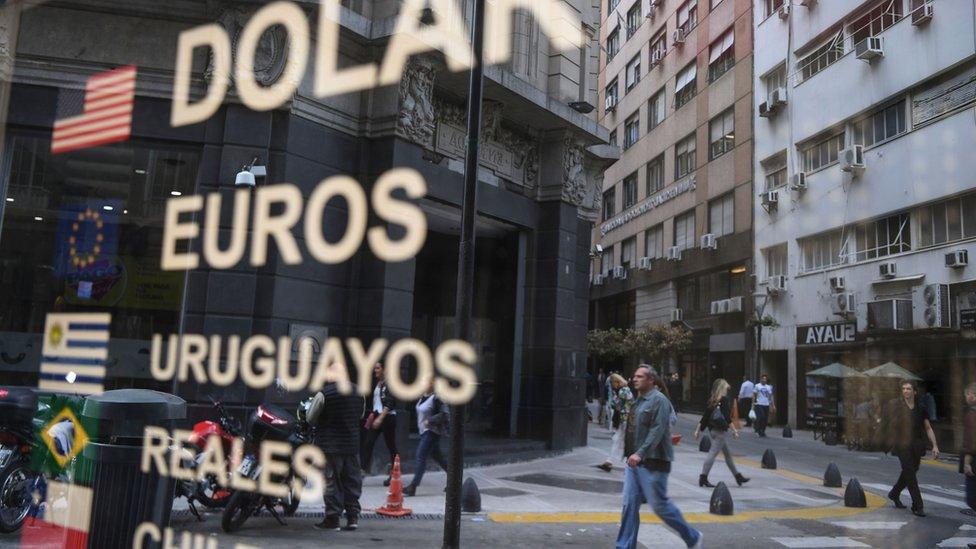

Restructuring talks

On May 22, Argentina defaulted on a $500m interest payment - the ninth default in its history - and it's currently in talks with bondholders over restructuring $65bn in foreign debt.

It said that with an economic crisis worsened by the pandemic, it was unable to pay its debts. But no agreement with bondholders has yet been reached. They've pushed back the restructuring deadline to 2 June 2 in an effort to come to a deal.

A sign says: "No to the payment of the debt. Break with the IMF"

"I think [default is] a ghost that's been walking around our country for so many years now, I don't think we're even afraid of it," says Constanza Guillén, an activist who's helping out at the kitchen. "The problem is how do we get out of this?"

A changed world

"[Argentina] wants to pay what they owe to the extent they are able to pay but you can't ask people to die to pay creditors," says Professor Joseph Stiglitz, one of more than 100 economists from across the world who wrote a letter calling for a constructive approach to the negotiation.

"They are playing as if the world hadn't changed," Professor Stiglitz says of bondholders. "The pandemic has made it clear that we have a global problem and when you make loans, you know there's a risk."

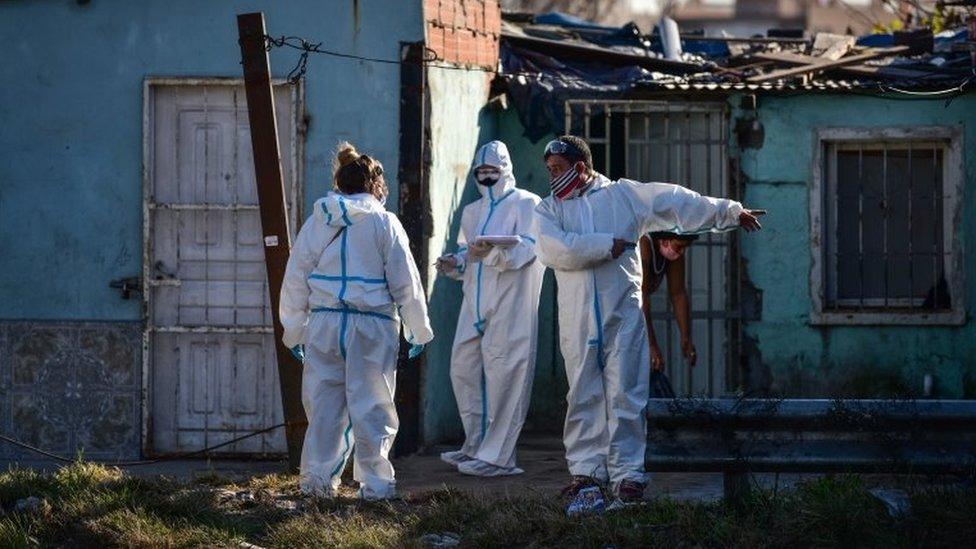

Not far from the soup kitchen is Vila 21-24, one of Buenos Aires' largest slums. It's these poor - and crowded - neighbourhoods that have seen an alarming rise in the number of Covid-19 cases in recent weeks.

"I never thought I'd go hungry again - or be unable to provide for my daughters," says 36-year-old Maira Ledezma, referring to the experience she had back in 2001.

Maira (pictured) recalls the difficulty of the last serious economic crisis

"Sure, I was paid badly but at least I had something," she says of her seamstress work, but with inflation at around 50%, she fears the worsening crisis will add to her struggles. "It'll make it twice as hard to get to the end of the month."

Empanadas for delivery

Husband-and-wife duo Florencia Barrientos Paz and Gonzalo Alderete Pagés are making just 20% of what they normally do at their restaurant Santa Evita in trendy Palermo. They've had to turn their restaurant into a delivery business. On the wall of the dining room is a smiling mural of the Argentinian icon Eva Perón. They aren't feeling so positive.

"It's like wartime, and we have to take every precaution possible, because if one of our people gets ill, we have to close again," says Gonzalo, who's cooking up empanadas in the kitchen. "And if we have to close again, we can't survive."

The new restructuring deadline is just days away

Florencia, though, is a little more sanguine.

"The truth is, we Argentines are used to being beaten up," she says. "We have fallen hard and developed coping strategies, especially when it comes to the economy."

So does she feel positive about the future?

"See this mask I have to wear? It's a bit like that - the reality is so present, I can't get think about anything else."

However, Professor Stiglitz says there's a lot riding on the success of Argentina's debt negotiations.

"If in the midst of this crisis, there's no humanity shown, no reason - and anyone understands you can't squeeze water out of a stone - people are going to turn against market economies more generally," he says.

"They are going to say, what's the nature of finance? We helped the markets in 2008, we bailed them out and this is how they reciprocate in the midst of a pandemic?"

- Published11 May 2020

- Published2 September 2019

- Published21 August 2019