Chile's choice: Out with the old, in with the new?

- Published

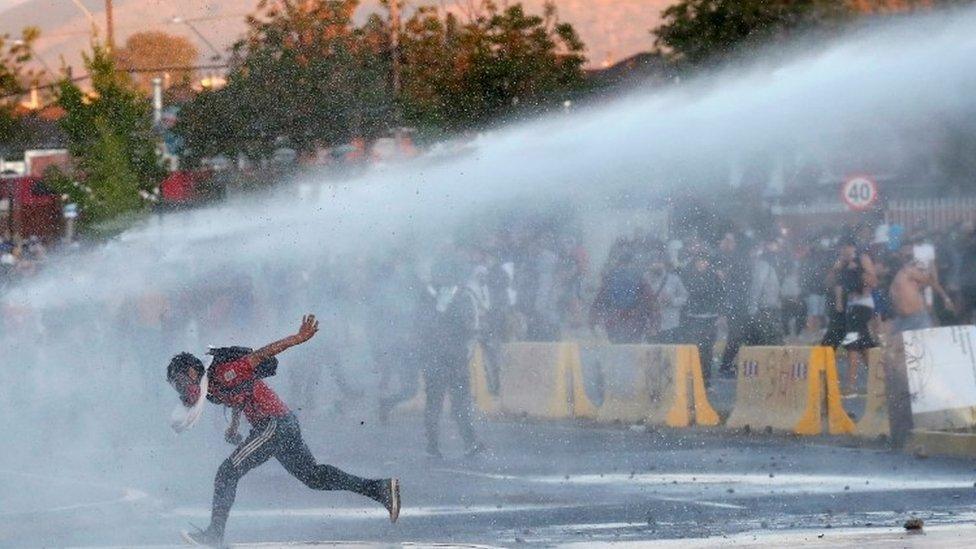

Clashes between the police and protesters often turned violent

Chile is a country used to earthquakes, but few expected the shake-up in Chilean society that we have seen this past year.

In just 12 months, Chile went from being an "oasis of stability", as President Sebastián Piñera described it, to a country about to tear up its old constitution and re-write the rules.

On Sunday, Chileans will be asked two questions:

Do you want a new constitution?

What kind of body do you want to draw it up? (Voters will choose between a so-called Mixed Convention, with 50% of members from Congress and the other half elected by voters, and one 100% elected by popular vote)

The expectation is that the majority will say "yes" to creating something new.

A new future for Chile?

This weekend will mark the end of a chapter that started in October last year. When Santiago's metro system hiked ticket prices by 30 pesos ($0.04; £0.03), authorities probably thought it was nothing. To many struggling Chileans though, it meant everything.

Students started calling for people to evade fares, spreading the hashtag #evasionmasiva (mass evasion) on social media. What started as fare evasions spread and evolved into mass protests with hundreds of thousands taking to the streets in the weeks afterwards, calling for an end to inequality that is all too familiar in Chile.

A week into the protests, on 25 October, hundreds of thousands filled the streets of Santiago

Poverty levels have dropped dramatically in the country over the last 20 years, but it remains one of the most unequal nations in the world. Many blame a system that has part-privatised services and utilities.

"Chile has woken up," they chanted. The anger may have flared up in an instant, but the resentment had been building for a long time. This is a country that had seemingly flourished, yet left many behind in the process.

Past protests

In 2006, high-school students protested against the country's education system in a series of demonstrations known as the Penguin Revolution - in reference to the black and white uniform the students wore.

Then in 2011, it was the turn of the university students to call for change.

Students took to the streets in 2011 to demand changes to the education system

From the very start, former student leader Felipe Parada has been out on the streets, taking part in cacerolazos, a traditional form of protest in Latin America which consists of noisily banging pots and pans.

Equal rights

"I'm one of thousands of Chileans convinced that it's possible to have a country that guarantees dignity for all - and not just for the privileged few," the 28-year-old says. "What we want is to have a constitution that guarantees equality and rights for everyone, with dignified conditions where there's no such thing as first and second-class citizens."

Felipe's parents, who lived through Chile's military rule between 1973 and 1990, warned him to be careful.

"We always live with the fear of our parents who fought against the dictatorship," Felipe says. But his mother Juana ended up joining in the pot-banging too.

Out with the old, in with the new

Chile's current constitution was drawn up in 1980, the result of a referendum under former military ruler Gen Augusto Pinochet. It has been tweaked over the years, but for many, those changes are not enough.

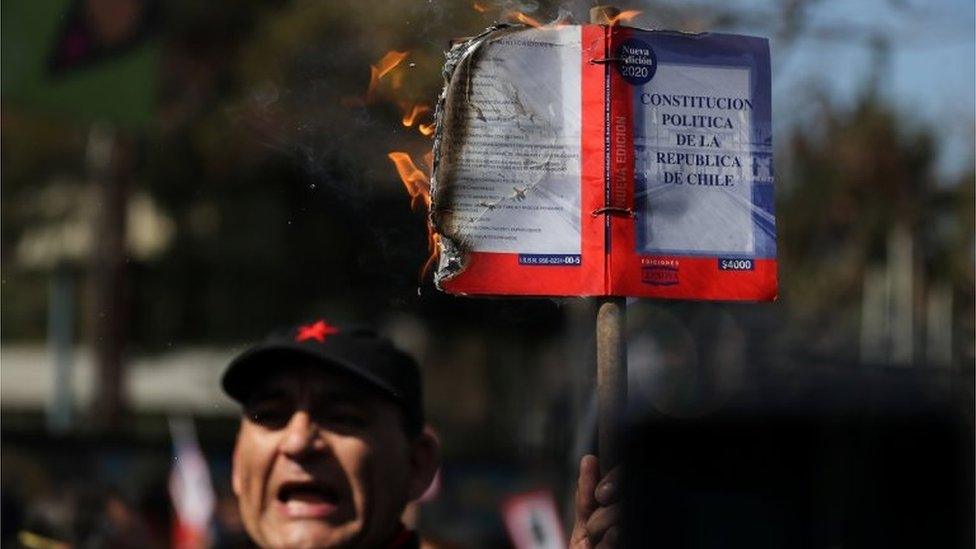

For many Chileans, the constitution is inextricably linked to the late Gen Pinochet

"Many social rights, because of the dictatorship and the civilian governments that came afterwards, are in private hands. Education, health, pensions, housing - they are businesses," says Camila Rojas, a member of parliament for the left-wing Comunes party.

Her party wants a new constitution that enshrines that these social rights be provided to Chileans for free.

Ms Rojas also criticises the power the constitutional court has over public policy. She argues that this has held Chile back from progressing. "The possibility of changing the constitution is the possibility, too, of starting to make changes to these areas," she says. "It's a historic moment."

Critics of the current constitution think it is time to draw up a new document

The plebiscite was delayed for six months because of Covid-19, but the pandemic has made the issues at stake even more relevant.

"The fact that the poor are the most affected by Covid is probably the most compelling data regarding all these social inequalities," says Claudio Fuentes, a political scientist at the Diego Portales University in Santiago. "I think this is why there are so many expectations on the plebiscite."

But there are Chileans who fear drawing up a new constitution now could herald economic instability at the worst possible time.

Rewriting history

"The origin of the constitution, and the origin of today's Chile is clearly illegitimate," says Patricio Navia, professor of liberal studies at New York University and a sceptic about Sunday's vote.

"No" campaigners want Chileans to show their rejection (rechazo) in the referendum

"It's based on the military dictatorship that violated human rights, but Chile needs to look forward and to build a better country. To some extent, if the 1980 Constitution is a house built by the rapist, by the human rights violator, the question is whether you fix the house or tear down the house because of who built it."

He argues that Latin America likes to re-write its constitutions - a symptom, perhaps, of a lack of faith in the region's institutions.

"The US constitution was written by slave owners, but the fact that the constitution allowed for the abolition of slavery, and the fact that the constitution has allowed for social inclusion, speaks to the ability of the people to build a more perfect union," says Professor Navia.

"Right now the debate in Chile is whether we want to rewrite history and deny the fact that Pinochet is part of our history. I think what we ought to do is build a better democracy rather than try to rewrite the past."

Is it rewriting the past or starting over with a clean slate? However you look at it, Sunday's vote will define Chile's future.

"Society has woken up," says Camila Rojas. "People aren't just prepared to vote, society is more empowered, more aware of what is happening in Congress, of government decisions, and I think that is going to continue."

Watch Katy Watson's interview with President Piñera from November:

Sebastián Piñera tells the BBC's Katy Watson that he is committed to remaining as president

- Published19 October 2020

- Published19 May 2020

- Published21 April 2020

- Published24 February 2020

- Published22 February 2020