Colombia Farc: The former rebels who need bodyguards to stay safe

- Published

Hundreds of former Farc rebels joined the march to Bogotá

After fighting with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) for more than two decades, Luz Marina Giraldo started a career in local politics and ran for a seat on the town council in Mesetas, a rural district in Colombia's eastern plains.

But her campaign ended abruptly last year when hooded men burst into her home and killed her partner, Alexander Parra, also a former Farc guerrilla fighter, shooting him five times in the back.

Ms Giraldo fled with her children to a nearby city and has not returned to Mesetas.

She is one of hundreds of former guerrilla fighters dressed in white T-shirts who marched into Colombia's capital, Bogotá, on Sunday to seek a meeting with President Iván Duque.

The protesters, who have been holding demonstrations in front of the presidential palace, say the government is not keeping up with commitments made in a 2016 peace deal that led to the disarmament of 13,000 fighters and transformed Latin America's oldest guerrilla group into a political party.

The new party retained the initials Farc but they now stand for Common Alternative Revolutionary Force.

The former rebels marched hundreds of kilometres to reach the capital

While the former fighters may have laid down their arms, their lives are still at risk from other guerrilla and drug-trafficking groups, and one of their key demands is for more protection.

"At this moment we face so many threats we don't even know where the bullets are coming from" says Ms Giraldo.

Carrying a white banner with a portrait of her late partner wearing a cowboy hat, she is followed everywhere by two bodyguards assigned to her by the Colombian government.

Luz Marina Giraldo carried a banner with a picture of her murdered partner

More than 230 former fighters have been killed since the peace deal was signed, according to human rights groups.

And even though it has now been almost four years since the peace agreement was signed, the rate of killing has not decreased.

The UN verification mission in Colombia says 50 former Farc rebels were killed in the first nine months of this year. In October, four more were murdered, according to human rights group Indepaz.

Among them was Juan de Jesús Monroy, a well-known ex-Farc commander who - after demobilising - had been leading farming projects in south-eastern Meta province.

His murder triggered the march on Bogotá, which was joined by about 700 former Farc rebels from different corners of Colombia.

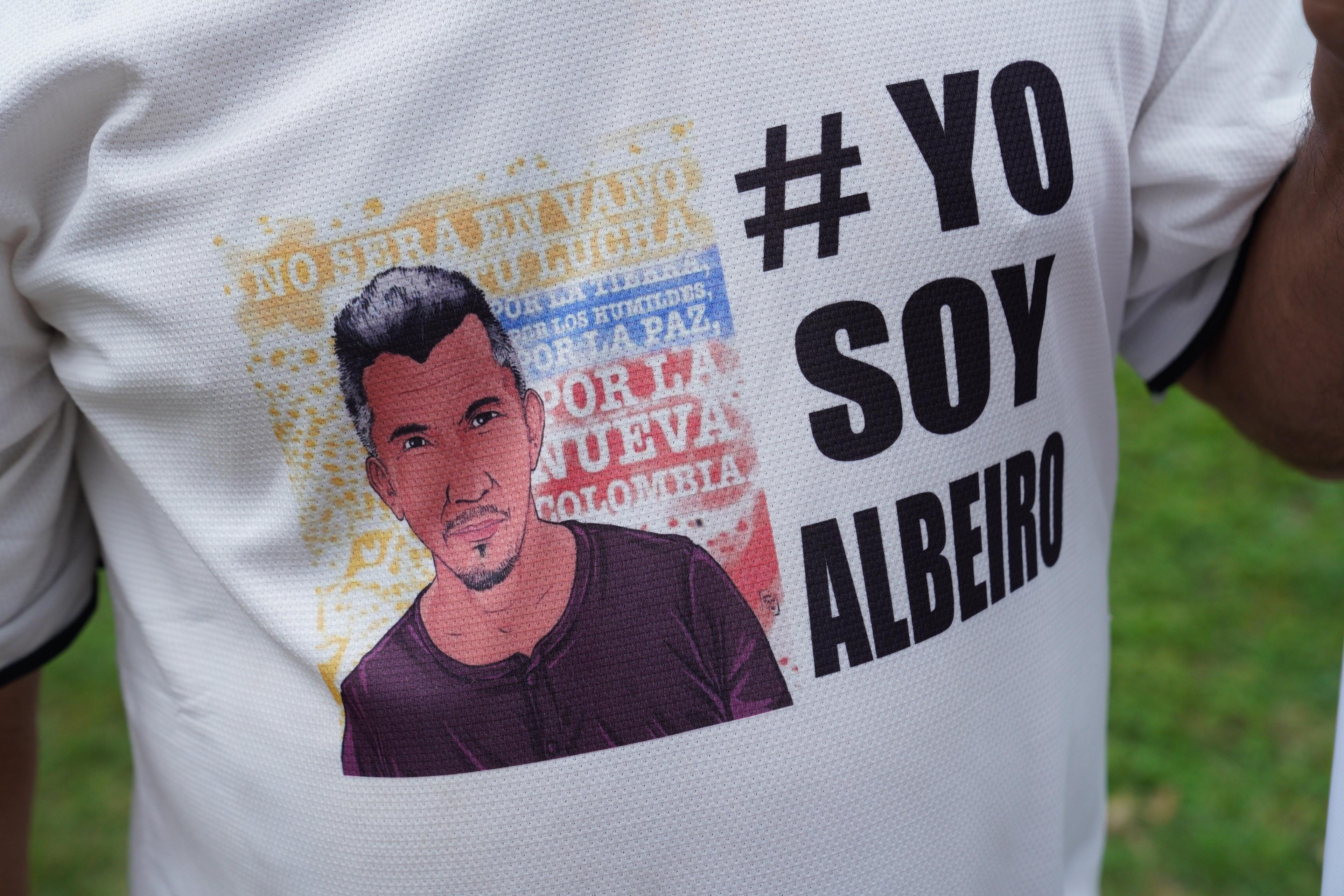

Many of those taking part in the march wore T-shirts with a picture of Jesús Monroy, also known as Albeiro

"The international community has to realise things are not going well," says Jesús Chaparro, a 50-year-old ex-rebel who has been working on a cattle-raising project managed by Mr Monroy.

He is part of a group that made the 400km-journey on buses to Bogotá and stopped at towns along the way to hold smaller rallies.

Juan Carlos Garzón, an analyst of Colombia's armed conflict at the Ideas for Peace Foundation, says the killings have happened mostly in remote rural areas previously controlled by the Farc rebels, where security has been deteriorating since the peace deal was signed.

In these areas a smattering of criminal organisations is now fighting for control of drug-trafficking routes, illegal mines and other resources abandoned by the Farc guerrilla after they demobilised.

Former Farc fighters who stayed there have been caught in the middle of the violence but now have no weapons to defend themselves.

"Some of these groups have old scores to settle" with Farc fighters, Mr Garzón explains. He says that criminal groups are trying to recruit former fighters and get farmers to grow coca, the raw material for cocaine. These groups target Farc party members, or anyone else who is trying to prevent that.

Organisations currently fighting over former Farc territory include drug-trafficking groups like the Gulf Clan, the National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrilla and dissident groups made up of ex-Farc fighters who did not want to lay down arms.

Colombia's Attorney General estimates that 70% of the murders of former Farc rebels have been committed by these groups but according to the UN, there have so far only been convictions in 31 cases out of more than 230.

A total of 236 former Farc fighters have been killed since the peace agreement was signed

"Our people are targeted because they are natural leaders" said Manuela Marín, a Farc party organiser based in Bogotá. "We are trying to generate transformations in these rural areas, and that clashes with criminal and political interests."

The Colombian government has attempted to protect former Farc fighters by assigning troops to watch over "re-incorporation villages", places where many former guerrillas live and work on farming projects.

Former Farc rebel leaders who are thought to be at greater risk are also assigned bodyguards and given bullet-proof vehicles. Currently there are 1,100 bodyguards who work with the National Unit for Protection and are assigned to former Farc rebels.

In October, Colombian government officials said that an additional 600 bodyguards would be hired to protect Farc party members.

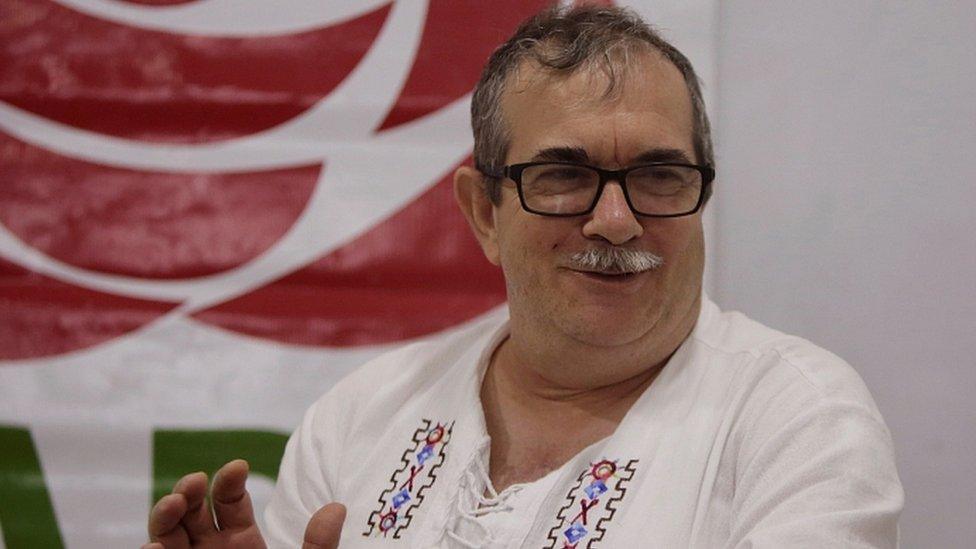

Senior Farc party members such as Pastor Alape are accompanied by bodyguards for their safety

The party has welcomed this help but its members say that for there to be a lasting improvement to their security and that of community leaders in rural areas, the implementation of the peace deal would have to be speeded up.

What the former fighters want to see is the dismantling of criminal groups and investment in rural infrastructure, so that people in those areas do not turn to the drug trade to make a living.

"Getting bullet-proof cars and bodyguards for 13,000 former fighters is impossible" says Tulio Murillo, a 54-year-old Farc party leader who has received death threats and has four bodyguards to protect him.

"What we need is greater commitment to the agreements that were made."

You may want to watch:

The BBC's Will Grant gained access to a Farc camp in Western Colombia

- Published15 September 2020

- Published17 August 2020

- Published12 January 2020

- Published30 October 2019