Colombian ex-Farc rebels 'ashamed' of kidnappings

- Published

Thousands of Colombians were kidnapped during the armed conflict from 1964-2016

Former commanders of the now disbanded Farc rebel group in Colombia have for the first time issued an apology for the kidnappings they carried out during the armed conflict.

A commission investigating crimes committed during 52 years of violence has promised more lenient sentences to those who admit wrongdoing.

Eight commanders called the kidnappings an "extremely grave mistake" and acknowledged the pain they had caused.

A peace deal was signed in 2016.

Thousands of people were kidnapped by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) rebel group over the decades. Some were freed after ransom was paid, others were held for years, sometimes chained to trees, and some were killed or died in captivity.

Eight former senior Farc commanders signed the statement in which they asked all of those they had kidnapped and their families for forgiveness.

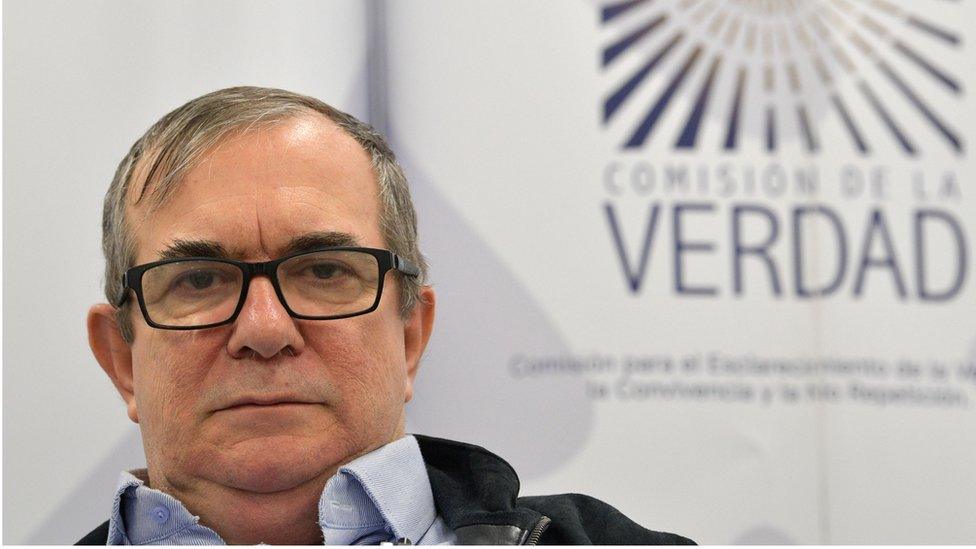

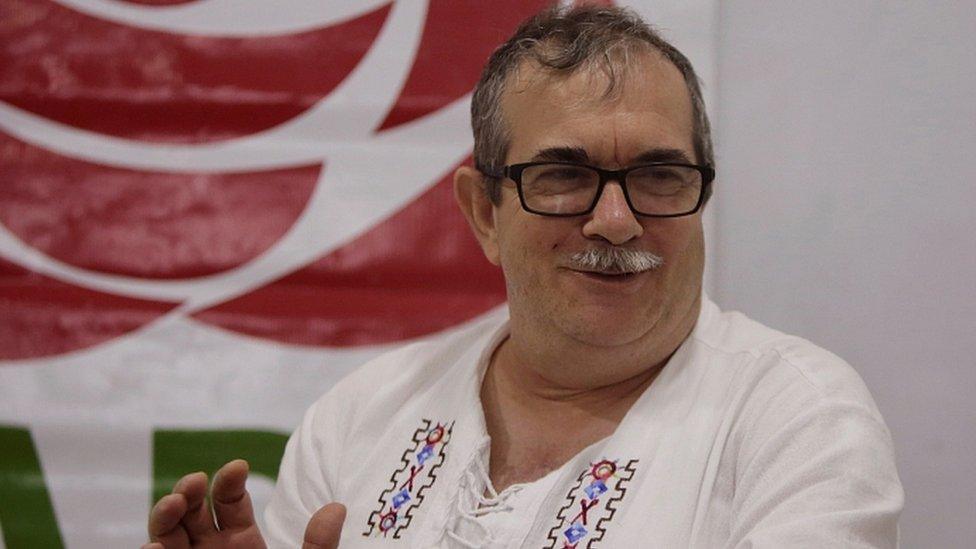

The Farc's former top leader, Timochenko, was among those who signed the statement

"We now understand the pain we caused so many families - sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, and friends - who lived through hell waiting for news of their loved ones, wondering if they were healthy and under which conditions they were held, kept apart from their affection, from their projects, from their world," the statement reads.

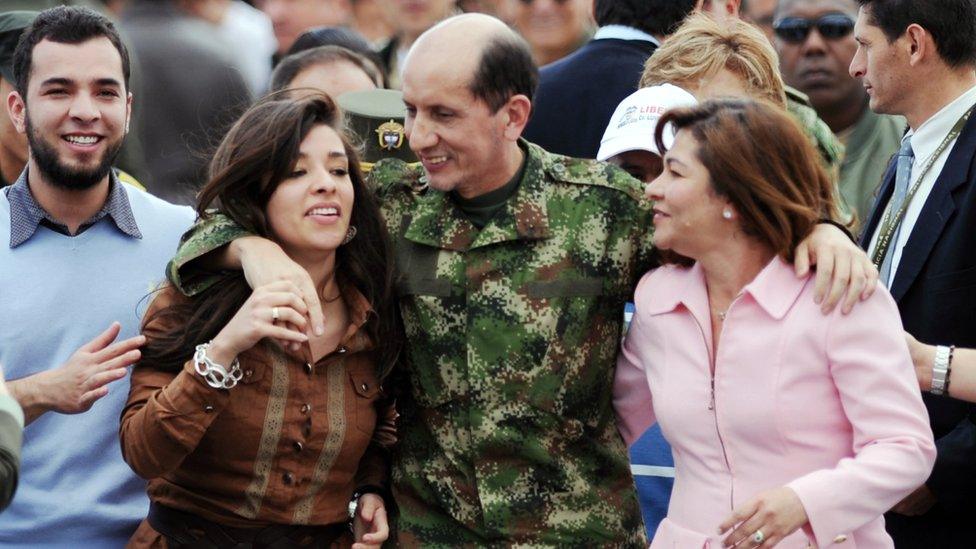

Luis Mendieta (C), a police general, spent almost 12 years in Farc captivity before being rescued by the Colombian army

The statement singled out the case of Andrés Felipe Pérez, a 12-year-old boy who had terminal cancer and who begged the Farc to release his father Norberto Pérez, a police corporal they had kidnapped in March 2000.

Footage of the boy pleading to be allowed to see his father one last time was broadcast on TV and became one of the most heart-wrenching images of the armed conflict, which lasted from 1964 to 2016. Hundreds of Colombians were so moved by his fate that they offered to go into rebel captivity in exchange for the boy's father.

The Farc refused, saying they would only release Norberto Pérez if one of their jailed leaders was freed, a demand the government refused.

Andrés Felipe Pérez died in December 2001 without having seen his father again. Norberto Pérez was shot dead four months later by the Farc while trying to escape after more than two years in captivity.

The Farc statement said ignoring the pleas of Andrés Felipe Pérez now made them feel ashamed and was "like a dagger in our hearts".

"We can't give the victims the time back that we stole from them, nor undo the pain and the humiliations we inflicted upon them, we can only reiterate our commitment to being held accountable before the justice system," the statement reads.

What's the background?

The signatories included Rodrigo Londoño, better known under his nom de guerre Timochenko, who was the Farc's top leader when the rebels entered into peace negotiations with the government which eventually led to the signing of a peace accord in 2016.

He and the seven other signatories are now members of the Farc political party, which they formed after they laid down their arms.

Crimes committed by all sides in Colombia's armed conflict are being dealt with by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), a transitional court system set up as part of the peace deal.

The JEP aims to bring to light all the crimes committed during the conflict and to that effect offers more lenient sentences to those who admit their crimes up front.

It has not been without controversy as many Colombians argued it let the rebels off lightly for the atrocities they committed while others argue that it is the only way for the truth about many crimes to emerge and for reconciliation

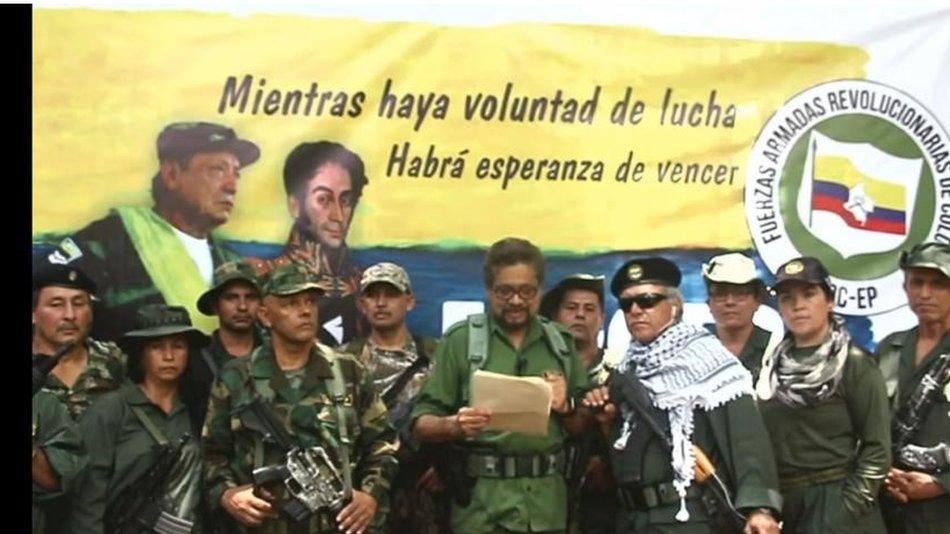

While most of its top commanders signed the peace deal, there are a substantial number of former Farc rebels who opposed the peace deal and who formed dissident groups.

In many rural parts of Colombia, those dissident groups continue to engage in drug trafficking, extortion and murder.

You may want to watch:

The BBC's Will Grant gained access to a Farc camp in Western Colombia

- Published17 August 2020

- Published19 June 2020

- Published12 January 2020

- Published29 August 2019