US-Mexico border: The gruesome attack that shocked a village

- Published

DNA work is under way in Guatemala to determine the identities of the other victims

When the burnt bodies of 19 people were found in two vehicles close to the Mexican border with the US last weekend, one village in Guatemala was particularly badly hit. Residents there are still trying to understand why some of them were killed in such a brutal way.

At the trials for his local football team a few years ago, Marvin Tomás impressed the team coach so much that he signed him up on the spot. A wiry, athletic winger with a vicious left foot, he fit exactly what the Guatemalan third division side, Juventud Comiteca, was looking for.

"He was left-footed, could attack, score goals - he was a very complete player," remembers the club's vice-president, William Matias. In fact, Marvin was so strong on the left flank he earned the nickname "Lefty" and was given the number 16 shirt.

Now though, the club have retired the jersey in his honour. Marvin was one of 19 Guatemalan immigrants who were killed in a brutal, gruesome attack in the state of Tamaulipas in northern Mexico last weekend. He was 22.

They were shot and then set alight, most likely by a drug cartel that controls the migrant smuggling routes across the US-Mexican border. Their charred remains are unrecognisable and William Matias says the sheer cruelty of the attack has shocked people in their rural corner of Guatemala.

"Their only crime was to flee hunger and poverty," says William.

"To murder people who were just en route to trying to find a better life - perhaps that's what hurts most."

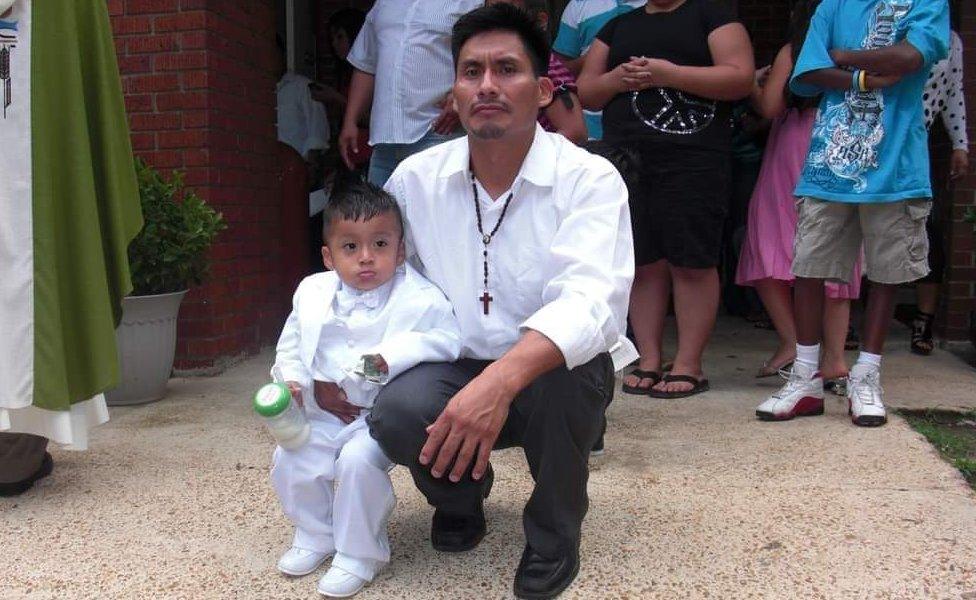

Marvin Tomás, one of the victims of the attack, was 22 years old

San Marcos is one of the poorest parts of Central America. Recent census data show the poverty rate in the department was some 15 percentage points above Guatemala's national average. But William's description reveals the grinding reality of his former player's life in a way that mere statistics cannot.

"Many families in San Marcos eat one meal a day - simple corn tamales or boiled potatoes. In Marvin's case, he was the only breadwinner after his father died from alcohol abuse," he explained.

"He would come to football training early, then work all day and study at the university at weekends. In an eight-hour day, he'd earn about six dollars. With that he had to support his mother and two young sisters, plus help out an older sister - a single mother on her own."

It is hardly surprising he decided to try his luck on the treacherous journey north. William believes the human-smuggler, or "coyote", charged the migrants as much as $12,000 (£8,800) for the trip. People often sell or mortgage everything they can to pay such a sum.

Tragically, Marvin was not the only migrant William knew who was murdered. His wife's uncle, Edgar López y López, was also on the fateful trip.

"Edgar was really like my own uncle too, I've known him for so many years. It was his 50th birthday on the day he was killed," William says. His voice falters on the telephone as he struggles to speak through the grief.

Edgar was not motivated to travel by economic necessity. Rather, he was trying to get home.

Edgar López y López was trying to return home in the US

He had lived in the US for 26 years and had a wife and two children in Jackson, Mississippi. Two years ago Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents raided the chicken factory where he worked as part of the Trump administration's crackdown on undocumented immigrants.

It would be the last time Edgar saw his family. He spent a year in a detention centre before being deported back to Guatemala. He undertook the risky journey north to get back to his children. It cost him his life in an area of scrubland in the violent border region between the states of Tamaulipas and Nuevo Leon.

In the wake of the attack, the United Nations Human Rights Office has drawn attention to two very similar massacres over the past decade to underscore the impunity with which they are still carried out: 72 migrants were murdered in San Fernando in Tamaulipas in 2010, and in Cadereyta in Nuevo Leon in 2012, 49 dismembered bodies were dumped on a highway.

The man believed to be behind these vile episodes was Miguel Angel Treviño, or Z-40, the jailed leader of the Zetas cartel. His nephew, Juan Gerardo Treviño Chávez known as "El Huevo", who heads a splinter group, is wanted in connection with this latest attack.

How Mexican cartels are taking advantage of Covid-19

Drug war analysts believe the motivation for such brutality against unarmed and impoverished immigrants is primarily to sow fear. The message is simple: if any immigrant intends to travel to the US through areas controlled by these gangs, they must go through them - and pay the corresponding extortion - or risk a similar fate.

William says that prospect will put some of his players off the idea of following in Marvin's footsteps, at least for a time. "In six months or so, the young people will forget and will try again," he says.

The Guatemalan authorities have started to take DNA samples from the victims' family members to send to Mexico for analysis in an effort to identify the bodies.

When Marvin's remains make it back to San Marcos, his teammates hope to drape his number 16 jersey over his coffin and bury him with the dignity that "Lefty" deserved.

Related topics

- Published25 January 2021