Has Honduras become a 'narco-state'?

- Published

Supporters of the opposition celebrated in Honduras when the president's brother was sentenced in the US

The former president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernández, has been linked to what US prosecutors call "state-sponsored drug trafficking" and was extradited to the US to face charges on 21 April, 2022 - but his name has been heard in court before.

Inside a New York courtroom, the president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernández, was known simply as "Co-conspirator 4".

Yet being stripped of the deference his position traditionally commands was the least of his concerns. US prosecutors now consider him to be intimately and demonstrably linked to violent drug cartels.

In 2019, his younger brother, Juan Antonio "Tony" Hernández, was found guilty of smuggling tonnes of cocaine into the United States during a criminal career that spanned over a decade.

To have your brother sentenced to life plus 30 years for drug trafficking would be a stain on any politician's record. But under the full glare of the world's media, prosecutors alleged his government was corrupt to its core - causing irreparable damage to his legitimacy as president.

And it is not just the case against his brother in which US prosecutors have identified the Honduran president.

During the recent trial in New York of Honduran drug trafficker Geovanny Fuentes Ramírez, the prosecutor painted a grim picture of Honduras as a "narco-state" where the cartels had infiltrated "police, military and political power… mayors, congressmen, military generals and police chiefs, even the current president".

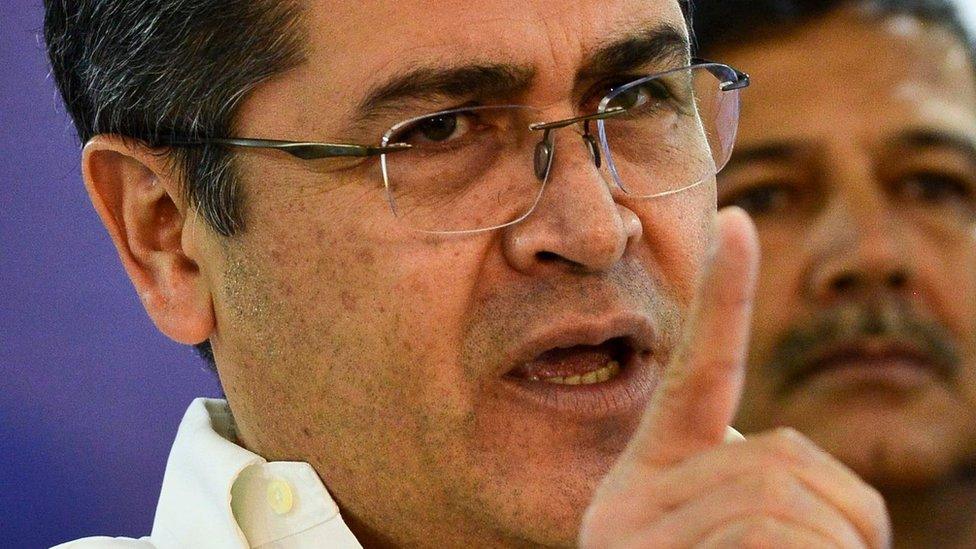

President Juan Orlando Hernández has denied the allegations against him

"In the 10 years before 2010, the traditional narcos had acquired so much political power in Honduras that they then began to co-opt the state itself to ensure their safety," says a former Honduran state attorney, Edy Tabora.

That period coincided with the rise of Tony Hernández in the drug world and his older brother into politics. Once Juan Orlando became president in 2014 and Tony Hernández a member of Congress for the National Party, they were effectively "narco-politicians", alleges Mr Tabora.

'State-sponsored drug trafficking'

President Hernández called his brother's sentence "outrageous" and repeated his constant refrain that the conviction was based on the testimony of known criminals with an axe to grind.

Tony Hernández was found guilty of receiving $1m (£720,000 in current figures) from the notorious drug lord, Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzmán, for his brother's election campaign.

US prosecutors also allege that President Hernández accepted bribes in exchange for the protection of his security forces and planned to "shove the drugs right up the noses of the gringos", referring to potential foreign users.

It was, they argued, nothing less than "state-sponsored drug trafficking".

The accusation is that - unlike countries where drug cartels work in tandem with corrupt elements of the state or the security forces - in Honduras the drug traffickers are the state, the very same people who control the apparatus of power.

President Hernández points to the seizure of large drug hauls as evidence that he is fighting the drugs trade

"That's the most important point to understand about Honduras", argues Mr Tabora. "The problem here is that the public functionaries wanted control over the drug trade."

The BBC asked President Hernández's office for an interview or a statement. So far, neither has been provided.

"We're talking about an entire political class," says Jennifer Ávila, editor-in-chief of Contra Corriente, a digital media outlet in Honduras.

"We've seen former parliamentary deputies on trial and members of the economic elite, one of whom is standing for president this year," she says, referring to Yani Rosenthal, a presidential candidate for the opposition Liberal Party who was convicted of laundering money for the Cachiros cartel in 2017.

'He may try to remain in power perpetually'

Juan Orlando Hernández is a headache for US President Joe Biden. He is the first sitting Latin American president since Manuel Noriega in Panama in the late 1980s to have his name so closely linked to drug trafficking in a US court.

One might expect the White House and the state department to impose sanctions or, at the very least, distance themselves from the alleged "narco-president". Instead Washington's economic and security interests are undoubtedly at play, especially regarding undocumented immigration.

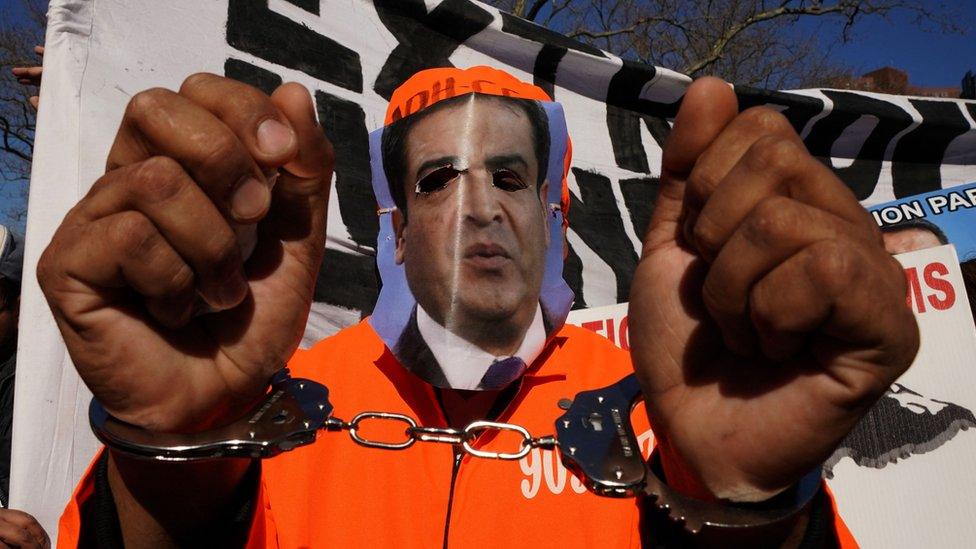

The sentencing of Tony Hernández shone a spotlight on Honduras

Honduras was quick to comply with President Donald Trump's harshest policies on immigration but as his brother was convicted, President Hernández indicated that bilateral security co-operation could "collapse" over the affair.

"At this moment he is the elected president of Honduras, we are going to work with his government, we are going to look for areas of common interest," said Juan González, President Biden's top adviser on Latin America.

"It doesn't surprise me," retorts Jennifer Ávila. "What most interests the US is preserving governability. They don't want a political vacuum or a transitional government because that would bring more instability to Honduras and generate more migration."

Were Juan Orlando Hernández to be forced out, she says, the country simply "isn't prepared for a crisis of that magnitude".

"Narco-government": The president has faced protests in recent years demanding his resignation

Washington appears to prefer the status quo - even one tainted by drug money.

"When Trump left office, clearly we'd hoped for a different position from the Biden administration," explains Gabriela Amador of the Pro-Honduras Network, an anti-corruption group of US-based Hondurans that covered every moment of the trials in New York.

"What worries us as Hondurans is that it's been shown that cartels have invested millions into politics and Juan Orlando Hernández may try to remain in power perpetually through fraudulent means."

His previous election win in 2017 sparked violent protests after the vote count was considered untrustworthy by international election observers.

Why thousands are calling for President Hernández to step down

Although President Hernández refutes the allegations, the convictions obtained by the US Department of Justice reveal a country mired in drug-related corruption - a description which former state attorney Edy Tabora reluctantly accepts about his homeland.

"The prosecutors in New York put it best when they called Honduras a 'corrupt narco-state'," he says, "because both mechanisms - corruption and drug trafficking - were used to seize the state's resources."

Related topics

- Published31 March 2021

- Published1 May 2020

- Published3 October 2019