Sacred objects: From police evidence to museum pieces

- Published

Among the items is a headpiece engraved with the name "Oxun", an orisha (deity) associated with rivers and waterfalls

One of Mãe Nilce de Iansã's childhood memories is hearing her aunt saying over and over again: "We have to get back our things from the police!".

"Do you know what happened to our things that were taken by the police?", her aunt, a Candomblé leader called Mãe Meninazinha de Oxum, would ask other people who visited the terreiro, the place where followers of Afro-Brazilian religions gather to worship.

For a long time, Mãe Nilce says, she did not know what her aunt was referring to. But over the years, she began to hear stories about how, in the past, police officers had stormed their terreiros and seized religious objects.

It was all part of a crackdown dating back to the late 19th Century on what authorities labelled "black magic". The items would be seized to never be seen again by their owner.

But last September, some of them were finally "freed".

Religious leaders and academics will join forces to identify the recovered objects

Seventy-seven boxes which had been gathering dust at the premises of the police in Rio de Janeiro were transferred to the Museum of the Republic. They contained more than 500 objects of worship seized by the authorities between 1889 and 1945.

Mãe Meninazinha, who is in her 80s, was ecstatic when that happened, as she and other Afro-Brazilian religious leaders had spent decades trying to retrieve them.

In 2017, their efforts were bolstered by Our Sacred, a documentary that told the story of the movement to retrieve the items. The campaign picked up speed and federal prosecutors took on the case, eventually striking a deal for the items to be moved to the museum.

It was also agreed that everything, from their storage to research to the design of the exhibition, would be guided by a commission of practitioners of Afro-Brazilian religions, so the objects are treated in keeping with their significance.

Those involved described the items final release from police headquarters as an act of "historic reparation".

The objects belonged to practitioners of Umbanda and Candomblé

After slavery was abolished in Brazil in 1888, the cultural and religious practices of the Afro-Brazilian population continued to be targeted by the state, and the 1891 penal code criminalised "spiritism" and "magic healers".

Art historian Arthur Valle says the racist worldview at the time meant that Afro-Brazilian religions such as Candomblé were viewed not as a religion but as "charlatanism".

Afro-Brazilian religions

Are rooted in the beliefs and cultures of African people brought to Brazil during slavery

Originated in different regions of Africa

The main ones are Candomblé and Umbanda, which are oral traditions with no holy scriptures, but there are many others

Candomblé means "dance in honour of the gods", and is a mixture of traditional Yoruba, Fon and Bantu beliefs. Music and dance are important parts of ceremonies, and there is no concept of good and bad

Umbanda, or "art of healing", combines elements of Candomblé with Catholic, spritist and indigenous traditions

Brazil had just cast aside the monarchy and was becoming a republic.

"A national project was emerging. In this nation under construction there was no room for practices considered 'uncivilised'. The model was 'rational', white and European," historian Valquíria Velasco says about the mood in 1889 Brazil.

"There is overt religious racism and a sense of a 'civilising' project," she adds.

In practice, this meant that when the police heard about a place where people practiced an Afro-Brazilian religion, they would storm it, arrest those present and seize their sacred objects.

The items would later be presented as evidence of the alleged crimes committed by the practitioners.

Museologists will also aim to explain in which context the items were taken from practitioners

Some Afro-Brazilian religions incorporate traditional Catholic elements

The first time Mãe Nilce (mãe is Portuguese for mother) saw photos of the items, she was moved. They were very similar to the ones she uses in her religious practice, such as strings of beads and the tall drums called atabaques which are played during ceremonies.

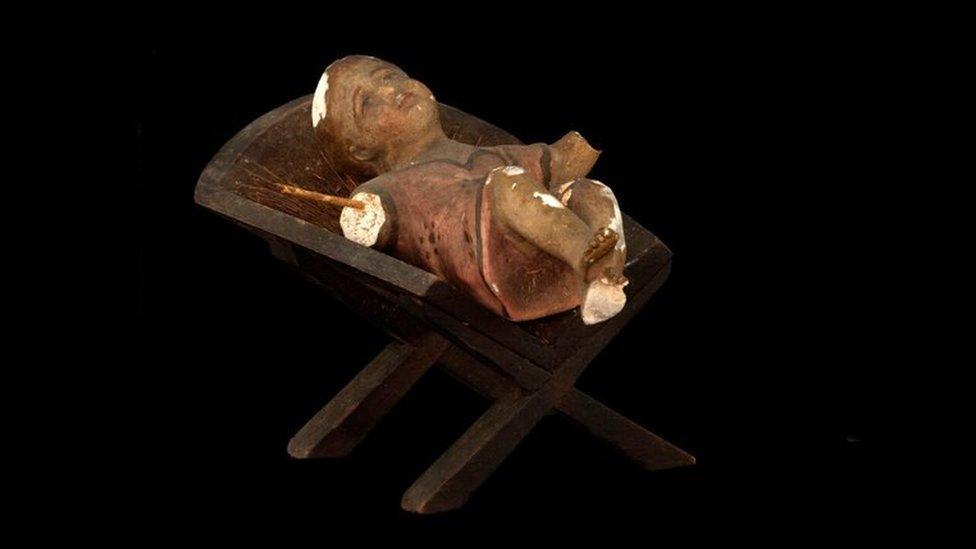

But they were all in poor condition, dirty, some broken, which made her sad.

Many of the objects were in a poor state

Museologists think the collection can help with the rediscovery of certain religious practices

Because the items were never properly recorded or studied, not much is known about their individual histories. But Arthur Valle, who studies the period of religious repression, says he has identified a few of them.

The bust of a head, for example, is mentioned in a 1934 police report which described how a woman was arrested for practising her faith next to it.

Cowrie shells are often used for divination

Maria Helena Versiani, a historian and museologist at the Museum of the Republic, says the input from the religious commission is key because Afro-Brazilian religions have a very strong oral tradition. "It's essential to listen to them in order to acquire knowledge that is not registered in books," she says.

An exhibition of the objects is being planned for November, when Brazil marks Black Consciousness Day.

Mãe Nilce hopes it will prove educational for those who know little about her religion and also combat the still deeply ingrained intolerance against it.

Mãe Nilce de Iansã (left) remembers her aunt (right) asking for the items seized by police

Afro-Brazilian religions may no longer be considered criminal but even today its practitioners are sometimes targeted by extreme evangelicals which condemn them as "evil" and "the devil's work".

Gangs have also been known to drive out followers of Afro-Brazilian religions from their places of worship or even from their homes.

"There is still a long way to go," Mãe Nilce says. "I hope kids visit and learn about religious discrimination. No-one is born prejudiced against certain religions. It's important that people really get to know our religions."

You may also be interested in:

Conceicao and Lausmarina, women from different religions, hug cross the religious divide.