The Easter Island pianist playing for her home's future

- Published

Mahani Teave plays Handel's Suite No 5 in E Major

As sea levels rise and the climate changes, Mahani Teave's island home and its culture are increasingly under threat.

Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, is one of the world's most remote inhabited island - a 164-sq-km dot in the South Pacific Ocean. The nearest land is Pitcairn Island, a British Overseas Territory, 2,000km (1,200 miles) away; and Chile - under whose jurisdiction Rapa Nui has fallen since 1888 - is 3,800km to the east.

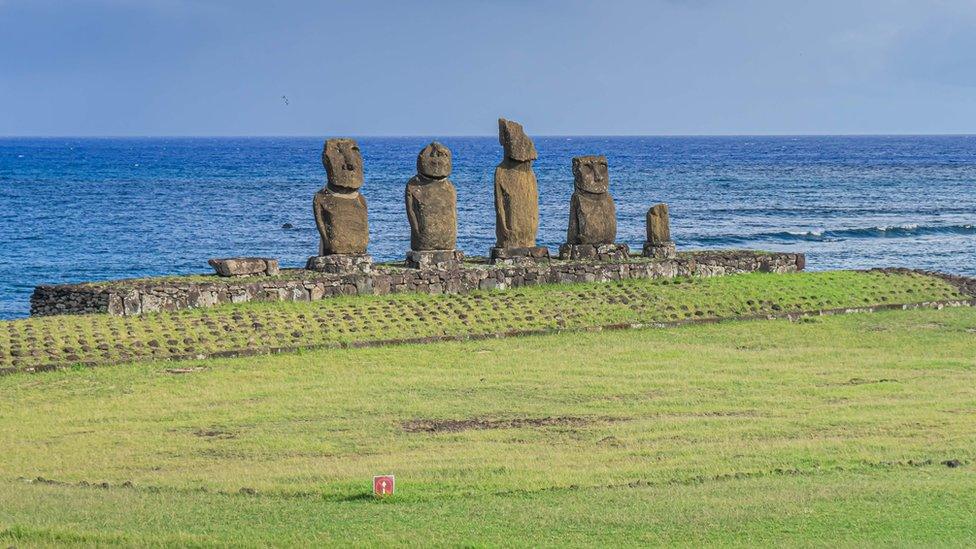

The undulating grasslands which roll away down its volcanic spine are dotted with more than 900 moai, the monolithic stone figures with which the island has become almost synonymous.

But the chart-topping classical pianist is part of a vibrant, living culture that encompasses far more than just the famous statues carved by her ancestors.

"I have this sense that Rapanui children learn to walk just so that they can dance and to speak so they can sing," says Teave, 37.

In 2016, she was one of 11 Rapanui who set up the Toki Foundation, a music and cultural organisation which mixes classical, traditional and ecological education to provide opportunities to young islanders in a society heavily reliant on tourism.

The students can learn to play a variety of instruments at the foundation

Children as young as two take introductory classes and older students learn the piano, cello, violin, trumpet and music theory. Some lessons are taught in the Rapanui language, and students can also learn ukulele, re'o riu (ancestral song), takona (body painting), and ori and hoko - two traditional dances.

Teave was born in Hawaii after her American mother had travelled to Rapa Nui and met her father, a musician. The family moved to Rapa Nui while she was young.

"I never felt isolated," says Teave. "When you're growing up somewhere like that then it's your whole world and it feels so big - there are still places on the island that I don't know."

When she was six years old, Teave took ballet classes and was captivated by the classical scores she heard while practising her steps - although the classes stopped abruptly when the ballet teacher moved away.

Undeterred, Teave convinced a retired pianist to give her lessons, practising for hours after school fearing that the reluctant teacher might put a halt to the classes and return to her peaceful retirement. At nine years old, Teave moved to Valdivia in southern Chile.

Mahani Teave grew up on Easter Island

"Leaving the island was a sour experience and I missed it so much," she remembers, "I couldn't understand why anyone should have to leave their home and people to do something as natural as play music."

Teave went on to study with Armenian-American pianist Sergei Babayan in the US before moving to Germany.

Although her career has seen her play in some of the world's most famous concert halls, it was the vulnerability of her culture and a glaring lack of opportunities on the island that drew her back to Rapa Nui in 2012 to found a music school.

"While I was abroad, I would think a lot about alcoholism, drug abuse and other social problems on Rapa Nui, and how these had a lot to do with the lack of opportunities," she says.

"It was on my mind that I belong to a culture that is on its way to extinction, and I always felt that there should be a music school on the island."

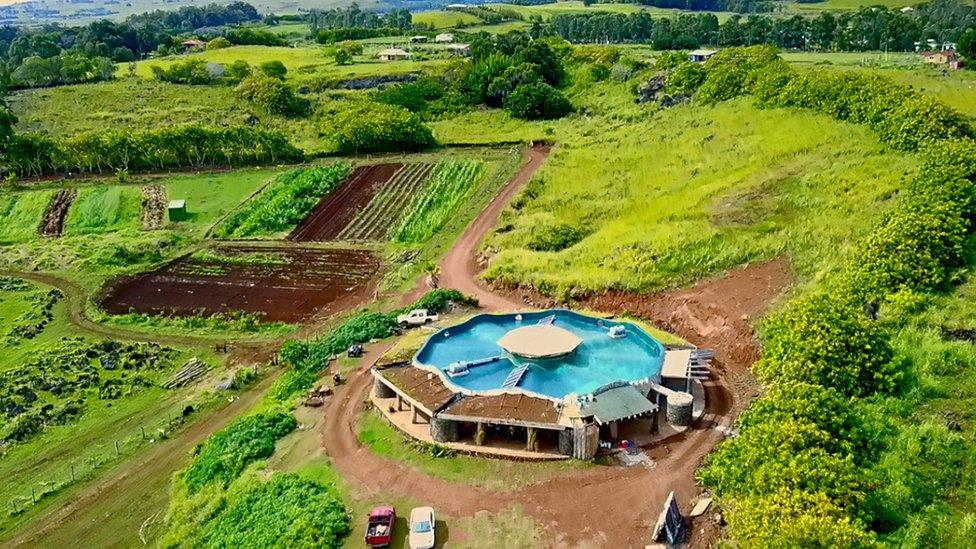

The school was built using rubbish left behind by tourists or washed up on Rapa Nui's shores

The school is self-sustaining with its own solar panels and rainwater collectors

One of Teave's first students was Rolly Parra, who moved to the island aged six when his father, a Chilean naval officer, was stationed there. He began learning the piano at the school, going on to win Chile's coveted Claudio Arrau Award for his performances in January 2017.

"I was inspired by Mahani and would copy everything she did," says Parra, "If she played a Chopin symphony then I would try to do the same, or if I heard her play particularly loudly or softly then I would do that too."

Teave's own career took an unexpected turn in 2018 when rare instrument collector David Fulton visited Rapa Nui on a world cruise and was astonished to learn that she had never recorded an album of her own.

Fulton offered to finance a recording and Rapa Nui Odyssey was released in January, shooting to the top of the US Billboard Classical Charts. The record cycles through some of her favourite pieces by Bach, Liszt, Handel and Chopin, and ends with a powerful rendition of I He a Hotumatu'a, Rapa Nui's anthem. All proceeds go to the Toki Foundation.

Back on the island, Teave and her colleagues are contributing to Rapa Nui's efforts to become sustainable and waste-free by 2030.

"The ancestral Rapanui worldview emphasises our connection with the Earth, which we are part of and responsible for," she explains.

Rising sea levels pose a threat to the island, located in the Pacific Ocean

The school itself took volunteers from all over the world a year and a half to build using six years' worth of rubbish left behind by tourists or washed up on Rapa Nui's shores - including tonnes of cardboard, cans, bottles and tyres. It is self-sustaining with its own solar panels and rainwater collectors.

The foundation's ecological work has taken on particular significance during the coronavirus pandemic, which gave a glimpse into a bleak future for an island heavily reliant on tourism and food imports: when tourist flights from Santiago were suspended in March last year, unemployment spiralled and food supplies dwindled.

Alongside cultural activities and litter-picking initiatives, the leader of the foundation's ecological project helped to co-ordinate 500 communal allotments and to encourage the use of manavai - traditional stone gardens which protect crops from erosion and preserve moisture - to alleviate food scarcity.

"We are already facing many of the challenges that are going to affect the world over the coming decade," says Teave. "If we can make this island 100% sustainable, then Rapa Nui can become an example for the world to follow."