Colombia gangs: 'Surrender or we'll hunt you down' warns minister

- Published

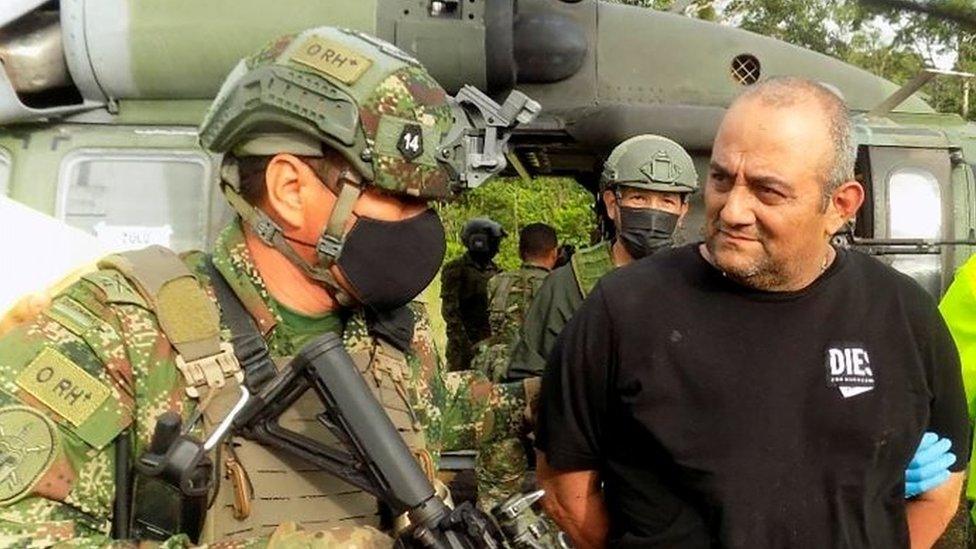

Dairo Antonio Úsuga, also known as Otoniel, was captured after years on the run

The capture in October of drug lord Dairo Antonio Úsuga was described by the Colombian government as "the most important blow to drug trafficking since the fall of Pablo Escobar".

While no one doubted that the arrest of Úsuga constituted a significant victory for the security forces, some in Colombia questioned whether the Gulf Clan he led could be compared to Pablo Escobar's Medellín cartel and the immense power it wielded in the 1980s and 90s.

Some analysts also warned that the capture of Úsuga, who is better known under his alias of Otoniel, could lead to a spike in violence as other drug traffickers rush to fill the vacuum created by his arrest.

But in an interview with the BBC, Colombian Minister of Defence Diego Molano insisted that Otoniel's arrest spelled "the end of the Gulf Clan".

Diego Molano has been defence minister since February 2021

Mr Molano said that Otoniel had ruled the Gulf Clan - a transnational criminal organisation engaged in drug trafficking and other criminal activities such as extortion - with an iron fist and that his capture had left the organisation rudderless.

"I recently spoke to one of Otoniel's men who has surrendered and he told me: 'He [Otoniel] was in control of everything, he was like our father, he was the one in the know, the one who controlled everything'."

Mr Molano said that, nevertheless, Colombia's security forces had not let up the pressure since Otoniel's arrest but were now on the hunt for his deputies, known as "Siopas" and "Evil Shorty".

Dairo Antonio Úsuga was led away in handcuffs following the raid

And Otoniel's men are not the only ones the Colombian military and police are after.

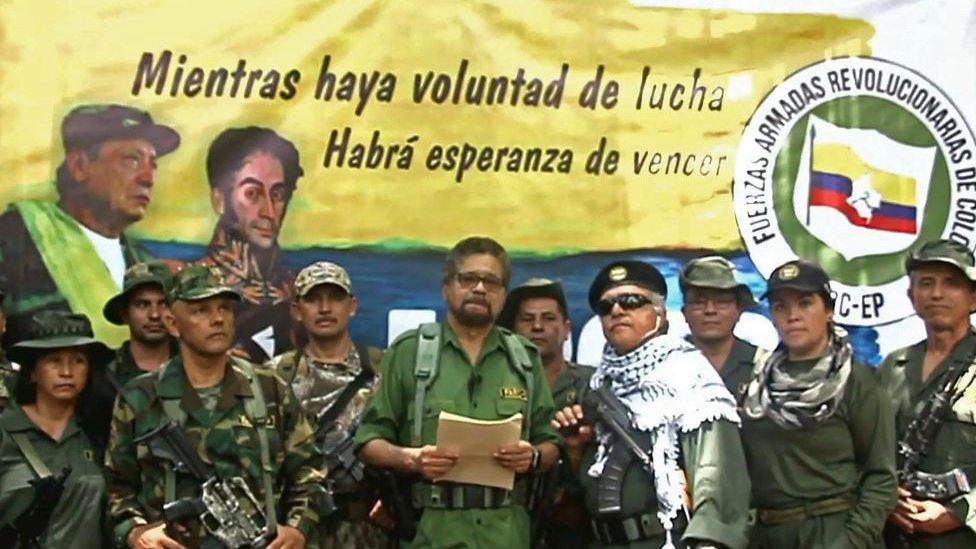

Five years after the implementation of a peace deal with Colombia's largest rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), the country is by no means free of armed gangs.

According to Mr Molano, these gangs have 13,000 members, half of them armed and half acting as support.

There are dissident groups made up of former Farc rebels who objected to the peace deal, members of another Marxist guerrilla group, the National Liberation Army (ELN), as well as right-wing paramilitary groups and criminal gangs such as the Gulf Clan.

For all of them, Mr Molano has one message: "Surrender, or we'll hunt you down."

It is these groups, which finance themselves mainly through drug trafficking, that are behind much of the violence which continues to blight Colombia and has forced thousands of families to flee their homes.

Official figures suggest that in 2021, the number of displaced families jumped by 213% compared to 2020.

The number of children forcibly recruited by gangs also remains high, as does the murder rate of environmentalists and social activists, who defend land and human rights.

For Colombia's defence minister, the key to bringing down the violence lies in tackling the drugs trade.

According to the United Nation's Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Colombia remained the world's largest producer of cocaine in 2020, even though it had managed to reduce the area planted with coca - the plant used to make cocaine - by 7%.

"Each hectare planted with coca means more deaths, more destruction of the environment, more murders of social activists," Mr Molano told the BBC.

Mr Molano said that cocaine seizures had increased significantly in 2021 compared to the previous year and that the security forces had destroyed thousands of laboratories in which the base for cocaine is produced from coca leaves.

The security forces have been targeting coca labs, which are often hidden deep in the jungle

But while Colombia's criminal gangs mainly finance themselves through drug trafficking, the government is also deeply worried about some of the gangs' other criminal activities - such as illegal logging and illegal mining.

Government figures suggest that in 2020, deforestation rose by 8% compared to 2019, with nearly 64% of the deforestation taking place in Amazonian areas, which are havens of biodiversity.

Mr Molano thinks that combatting the criminal structures behind the cutting down of trees for the illicit trade in timber or to make way for coca plantations is key to protecting the Amazonian region.

He welcomed a move by the attorney-general's office two weeks ago in which three leaders of break-away Farc groups had been charged with environmental crimes.

While the three - known as Gentil Duarte, Iván Mordisco and John 40 - are on the run, Mr Molano thinks that the charges send a strong signal that Colombia will go after those who engage in criminal activities that harm Colombia's unique flora and fauna.

Related topics

- Published25 October 2021

- Published6 December 2021

- Published13 September 2021