Cuba's first gay hotel reopens as human rights deteriorate

- Published

Dancers perform with rainbow flags at the Rainbow Hotel, described as Cuba's first LGBTQ hotel

As members of the press arrived for a government-organised tour of a luxury hotel on the Cuban beach resort of Cayo Guillermo, they were greeted by a dance troupe in fishnet tights and high heels.

Above the entrance, the rainbow flag, the international symbol of gay pride, fluttered in the warm Caribbean breeze.

The Rainbow Hotel, described as Cuba's first LGBTQ hotel, reopened in December.

While guests enjoyed the five-star service by the pool or a walk along the pristine sands, Cuba has not always been so welcoming to the gay community. In the early part of communist leader Fidel Castro's rule, homosexual men and women were sent to work camps for supposed "re-education".

Of course, since those dark days, attitudes on the island have markedly improved. The Cuban government and MGM Muthu Hotels, the company behind the Rainbow Hotel, say it exemplifies that change in attitude.

The hotel is part of a strategy by the authorities to attract deep-pocketed gay tourists

A joint venture between Muthu Hotels and Gaviota, Cuba's military-run tourism company, the Rainbow Hotel was placed on a US government list of sanctioned entities in Cuba even before it was inaugurated in 2019.

Then the coronavirus pandemic struck and it lay empty and unused for the next two years. Now though, tourists are arriving. "It's nice to be able to be in a place where you feel welcome and encouraged to be yourself," Kevin McGarth, from Toronto, says, describing the hotel as "an oasis in the Caribbean".

"When we got here we signed a waiver saying tolerance is the only way here and that if you're not tolerant of people you'll be asked to leave."

Beyond the hotel's perimeter, however, tolerance has been noticeably absent in Cuba recently.

Following island-wide anti-government protests in July, the authorities have clamped down on all forms of dissent. Mass trials of detainees have been held behind closed doors with the state seeking decades-long prison sentences for some defendants, including minors.

Some activists say the hotel is an attempt by the state to mask its poor human rights record

In November, a second protest was stopped before it could begin by a huge presence of state security and police on the streets. One of the organisers, Yunior García, was forcibly kept inside his home, unable to even signal from his window before government supporters placed a huge Cuban flag across the building.

Mr García left the island soon after. In fact, many activists and independent journalists have gone into exile in recent months, saying the authorities have made their lives unbearable.

Amid such harsh treatment, some Cuban gay rights' activists say the Rainbow Hotel is an attempt by the state to mask its poor human rights record.

"Every visitor to Cuba is, of course, very welcome here," says Jancel Moreno, a LGBTQ activist in the city of Matanzas. "But I'd invite the hotel guests to investigate a little into the repression we receive as independent activists."

Any type of protest or gathering or even writing a report into human rights, he says, is met by uncompromising authoritarian control. "I'd ask them to see all that and to look beyond just the beautiful beaches or the number of stars a hotel has," Mr Moreno adds.

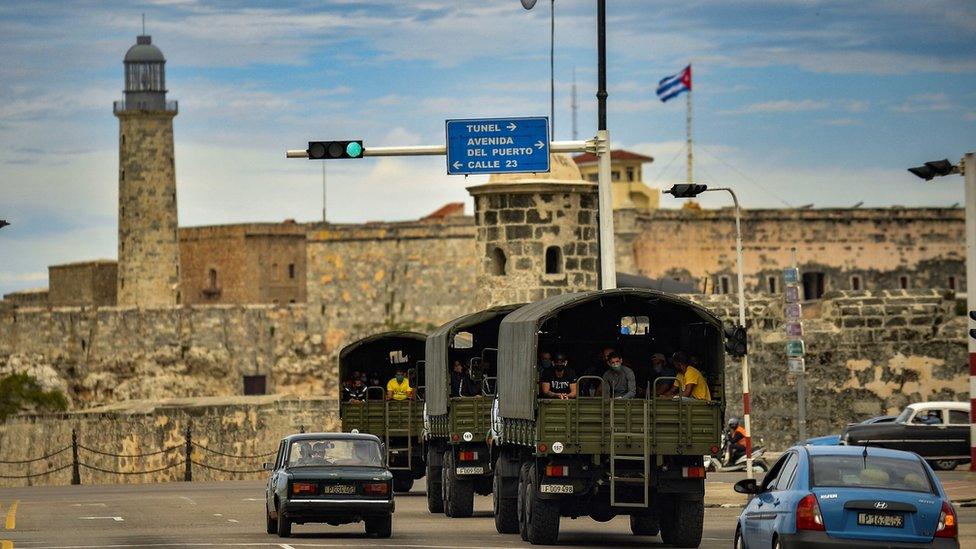

A huge presence of security forces prevented a second anti-government protest from happening last November

Away from the beaches, Old Havana normally bustles with tourists. But amid an estimated 70% slump in tourism over the past year, a long line of 1950s convertibles lies idle outside Parque Central.

Normally they would be doing a roaring trade taking scores of visitors to see the city's landmarks, tour operator Mario Lopez says. We chat in front of the Hotel Telegrafo, due to be unveiled soon as Cuba's second LGBTQ hotel as the state doubles down on its pursuit of the gay tourist dollar.

If the government's push towards gay tourism can help reignite business, says Mr Lopez, he is all for it. The last two years have been brutal.

"The normal price for one hour's tour is about €60 (£50; $70). But that was before coronavirus," he says in fluent English. "Now I can only ask €20. It's hard for the Cuban people right now."

FROM THE ARCHIVE: 'We've been begging'

The inauguration of gay hotels comes as the government is about to put a change to the country's "family code" before the people. A national debate on modernising the law is due this month which could lead to a referendum on legalising same-sex marriage later this year.

Activists, including Jancel Moreno, are hopeful that the long-awaited change may soon become law. Yet, he says, even the gay rights struggle in Cuba has been co-opted by the state.

Raúl Castro's daughter, Mariela Castro, heads the state's sexual health institute, Cenesex, which acts as the officially-accepted lobby for LGBTQ rights.

Cuba has seen a huge drop in tourism because of the pandemic

In 2015, symbolic same-sex weddings were held at Havana's government-sanctioned gay pride march. But an independent gay pride march a few years later was quickly shut down.

Back at the Rainbow Hotel, most guests have set aside such debates as they enjoy some rest and relaxation. Yet activists see that as part of the problem.

Gay tourism is lucrative and Cuba certainly needs the income. They just hope all visitors - whether gay or straight - make themselves aware of the wider human rights context of their trip.

Related topics

- Published26 January 2022

- Published20 August 2021

- Published14 July 2021