'There's power in names': Antigua unearths lost ancestors

- Published

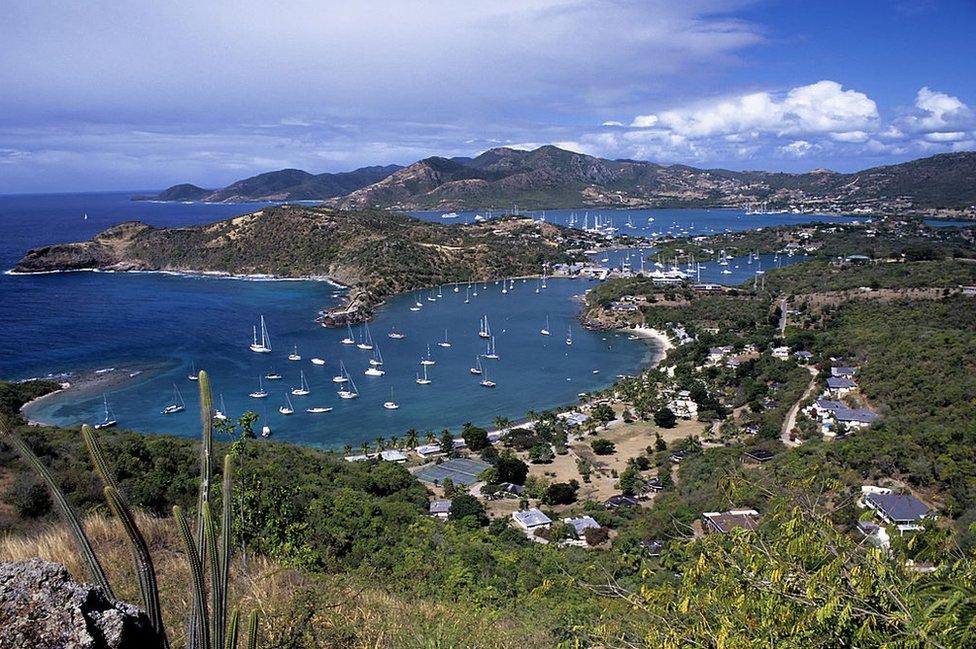

Nelson's Dockyard is today a bustling yachting hub and tourist attraction

At precisely 47.5 years old, house carpenter "Polydore" - surname absent - is cited as a "good workman" and the property of His Majesty King George. So reads a 1785 register of enslaved Africans in Antigua in which Polydore appears among hundreds of others.

Polydore's real identity of course was erased the second he was forced onto a ship in Africa bound for Britain's Caribbean colonies.

He was one of several thousand enslaved workers behind the construction and upkeep of Nelson's Dockyard, then a safe harbour for Royal Navy warships protecting imperialist Britain's prized sugar-producing islands.

Today it's a yachting hub, Unesco World Heritage Site and thriving tourist attraction as the Western Hemisphere's only working Georgian dockyard.

Local historians recently embarked on a ground-breaking project to formally identify the faceless people who built it, whose stories have been wiped from history.

Through the meticulous scrutiny of documents found in London's National Archives, corroborated with Antigua-based ecclesiastical records, they have already unearthed an incredible 700 names.

They are now in the throes of landmark genealogy work to link the country's modern-day residents - many of whom share surnames like Joseph, James, Henry and Gardner - back to their African ancestors.

For Desley Gardner, one of the researchers involved, the venture is "validating".

"Often we don't know for sure who our ancestors were. It's empowering to be able to put a name to these people - especially those who played such an integral role in the development of our country - and illuminate their presence in our history and heritage," she tells the BBC.

Heritage resources officer Desley Gardner says she hopes the work will be empowering to native Antiguans and Barbudans

Sugar's links to slavery

Britain's taste for sugar in the 18th Century gave rise to the spread of sugar plantations, creating a need for workers. Millions of enslaved Africans were taken to the Caribbean to harvest the cane.

Enslaved people were stripped of their names and identities and shipped in the holds of vessels like cargo. The transatlantic crossing took several weeks and many people died en route.

In the mid 18th Century, enslaved people generally lived just three years after stepping off the boat from Africa in the eastern Caribbean due to the atrocious living conditions.

By 1750, sugar had surpassed grain as the most valuable commodity in European trade, making up a fifth of all European imports.

Slavery officially ended in the British Caribbean in 1834. Today emancipation is celebrated in many islands in the form of Carnival.

Justine Henry, who recently joined the research team, has tried in the past to trace her family history with limited success.

"I would love to see where the work leads, and who I might be related to," she says.

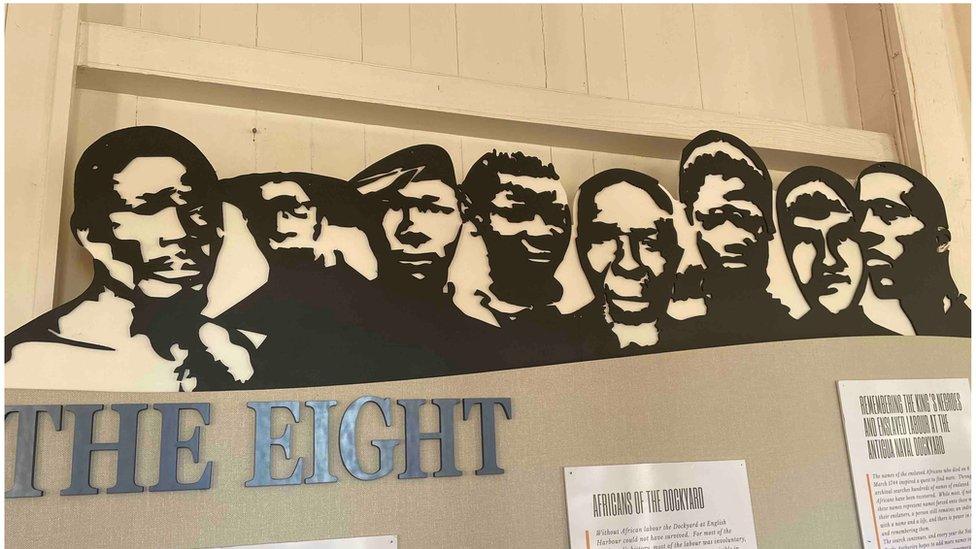

The project was inspired by the discovery of the names of eight men who died in a gunpowder explosion at the dockyard in 1744. They had been recorded by plantation owners seeking compensation for the loss of their property.

The researchers knew if they could find eight names, they could likely recover more.

But it's laborious work due to "massive archival silence", explains Dr Christopher Waters who is heading the project on behalf of the country's National Parks Authority.

"Something we have to be very cognisant of is that these names are the ones that were recorded by the enslavers, as part of the dehumanisation process, to ensure these people were thoroughly incorporated into a subjugated role," the heritage department manager says.

Dr Christopher Waters hopes to help formally identify enslaved people who were erased from history

The original African names of those who arrived by ship may never been known. Others born into slavery were often named after plantation owners, slave vessels or derived from traditional English or Biblical names.

"We think there's a significant amount of power in these names, even if they're not their own, because it returns some of the personhood to these people that have been lost," Dr Waters continues.

Artists were tasked with creating faces to represent the eight men killed in the explosion, which are on display in the dockyard's museum.

"We have started to try to bring back people who have been forgotten, lost or intentionally erased from history.

"It's important to remember that slavery was the only thing that kept the dockyard going; the Royal Navy relied on it to ensure their fleet could succeed in the Caribbean," Dr Waters says.

Artists were tasked with creating faces for the first eight people named

As the painstaking endeavours continue, the team hopes that oral history, along with centuries-old journals and diaries, will help forge direct links with people still living today. The goal is to create an interactive website where residents can eventually do their own research.

"People have already been coming to us and asking questions. We aim to sit down with some who have done family histories plus some elderly residents, make our way through admiralty and church records and see what connections we can find.

"It's quite conceivable we are only three generations away from someone who was enslaved here in Antigua," Dr Waters notes.

More than 300 years after the first slave vessel arrived in the country, the maritime skills passed down over the years are evidenced today in the wealth of Antiguan-owned businesses offering everything from carpentry and varnishing to sailmaking and shipbuilding.

"These industries married African and European traditions here in the dockyard. They have persisted in surrounding communities and have evolved to suit the modern yachting industry," Dr Waters says.

"High-end yacht owners will tell you some of the most skilled people in the business are right here in Antigua."

The yachting industry benefits from maritime skills passed down through generations. (Pictured: A view of English Harbour)

Ms Gardner agrees.

"English Harbour is now a yachting mecca. And the people who were here back in those days provided the foundation for it," the heritage resources officer says.

For Ms Gardner, a native Antiguan, the ongoing research offers an opportunity to put an African perspective on a story defined by European colonists.

"I hope our work will be empowering to Antiguans and Barbudans," she adds. "It gives us the opportunity to be the tellers of our history. We can't change what happened but we can try and understand why and who it happened to."

Related topics

- Published28 February 2016