Unearthing Antigua's slave past

- Published

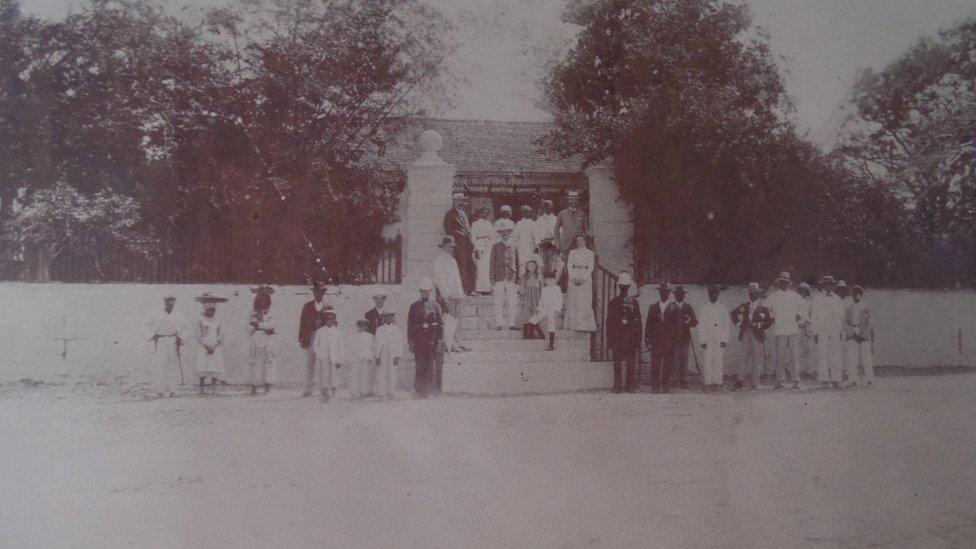

The former manager's house - one of several sites at what was one of the most productive sugar plantations in the West Indies

History, they say, is written by the victors.

Standing under the shade of a towering windmill at what was once one of the most productive sugar plantations in the West Indies, it is not hard to imagine the legion of imperious Englishmen at its helm.

But while an abundance of documentation scrupulously records the details of the industry which helped build the British Empire, precious little is known about the lives of the African slaves upon whom it hinged.

Students from California State University hope to shed light on 18th-Century life

Researchers probing an 18th-Century slave village amid a major excavation project at Betty's Hope plantation in Antigua hope to change that.

Slavery in Antigua

1674: Antigua's first sugar plantation is established with the arrival of Barbadian-born British soldier, plantation and slave-owner Christopher Codrington

Within just four years, half the island's population was made up of African slaves

Betty's Hope was the island's flagship plantation but Antigua was once home to as many as 190 others which relied on slaves for labour

One of Antigua's annually celebrated national heroes is the slave Prince Klaas who in 1736 planned an uprising which led to him being executed

Even after emancipation, many slaves continued to work on Antiguan plantations for a paltry wage due to scant alternatives.

One of just a handful ever unearthed in the Caribbean, the discovery of the site and recent artefacts is set to shine a light into a grim past.

Dr Georgia Fox, of California State University's anthropology department, is leading the research

Some of the items uncovered during excavation works at the plantation

Dr Georgia Fox, heading the project, describes the initial finding of the village in 2013, which had eluded archaeologists for decades, as a "eureka moment".

Aligning high-tech electronic surveying equipment with maps dating back to 1710 enabled one of her team of students from California State University, Chico, to pinpoint its location.

"It felt like a miracle," she told the BBC. "We'd seen all these dots on the maps and we now realised they signified the slave village. It was an amazing discovery."

Many sewing items, including needles, hooks and eyes, and buttons made of bone, metal and shells, have been recovered over the years

Imported ceramics, including Dutch delftware, unearthed in the slave village

Subsequent excavation works have turned up a wealth of fascinating relics which, for the first time, offer a glimpse into the daily lives and culture of the plantation's 400 slaves.

"First we found what appeared to be a very specific type of rough pottery, called Afro-Antiguan ware, made by slaves. Pots were created by coiling pieces of local clay and would have been used for cooking stews," Dr Fox explains.

"Recently we were able to go really deep into the heart of the village and we found some remarkable things like cowrie shells from East Africa which were used as currency, for games or good luck charms."

Piecing history together

This in itself raises interesting questions as slaves in Antigua tended to be from West rather than East Africa.

"Then we found Dutch delftware which was probably bartered for, traded or given to the slaves as hand-offs, followed by two corners of a beautifully made limestone wall which was tantalising as most slave homes were standard wattle and daub," Dr Fox continues.

Excavation by Dr Fox's team began in 2007 at the plantation's Great House, followed by the Still House where rum, then sugar's most important by-product, was made.

The once 700-acre site dates back to around 1650 and comprised a largely self-sustainable living complex accommodating everyone from field workers, servants and overseers to tradesmen, a blacksmith and a doctor.

At its height, each of the plantation's twin windmills could have produced 12 tonnes of sugar crystals a day.

A view of Great House at Betty's Hope sugar plantation, Antigua, 1904

Less than 5% of the sprawling site has been investigated so far.

Items uncovered at the Great House include children's toys, musket balls, buttons, cutlery, a door knocker, clay tobacco pipes and a cod liver oil bottle.

The organic materials used to build slave houses, such as palm fronds, sticks and mud, made the adjacent village's identification difficult.

Local historian and Unesco representative Reg Murphy, who oversees all of Antigua's archaeology projects, said the work was vital to piece together a complete history of the island where most of the population are slave descendants.

"Everything we learn is about the glory of sugar and the industrial colonial legacy," he says.

"You never hear about the day-to-day lives of the workers, the other side of the coin.

"This is a way of learning about their daily routine, what they ate, how they lived, seeing it from their perspective. There were over 400 slaves at Betty's Hope at one time - their stories have never been told."

As many as 400 slaves were at the plantation at the peak of operations

For Dr Fox, the significance goes further still. "There were sugar plantations throughout the world but the Caribbean was the gateway to the New World and had a tremendous impact on the development of America.

"This was the beginning of capitalism and it all started in the Caribbean. It's important to remember how the New World was created - this is everybody's history."

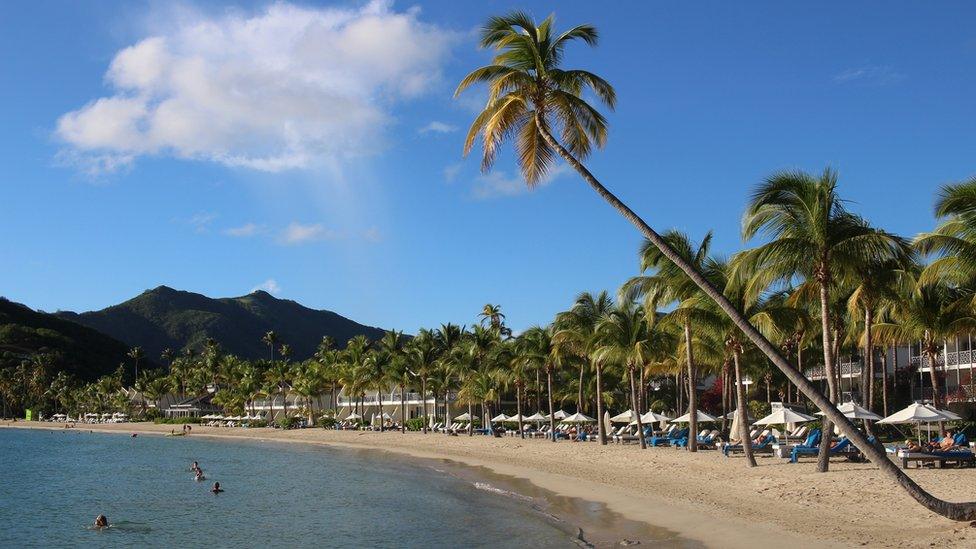

Although slavery was abolished in 1834, Antigua's sugar production remained an economic mainstay until the 1960s when it was replaced by tourism.

Dr Fox adds: "Sugar changed the world. Every time you bite into a chocolate bar or add sugar to your tea or coffee, you are taking part in a long history and reaching into the past."

Less than 5% of the sprawling site has been investigated so far - but excavations continue

- Published27 December 2015

- Published30 September 2015