Brazil's Bolsonaro and Lula battle it out for top job

- Published

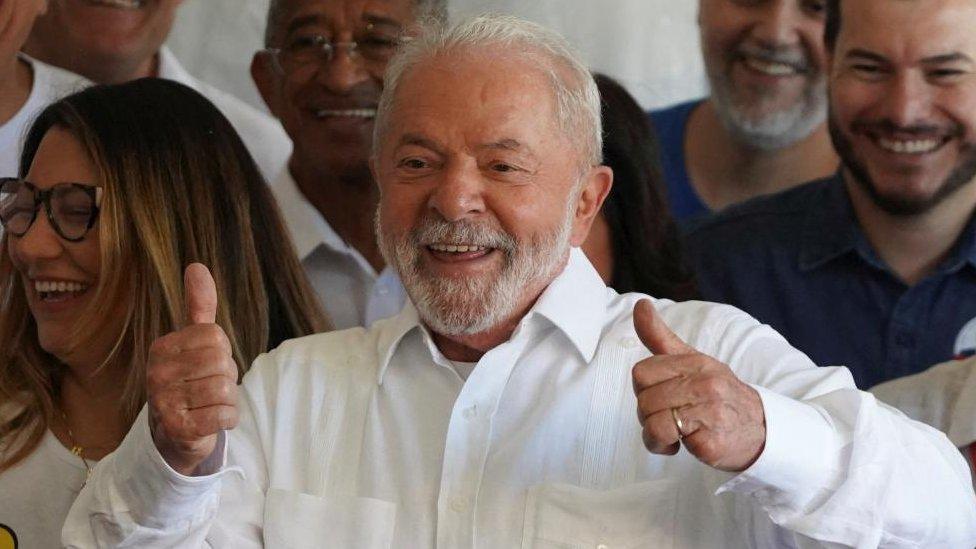

Lula (left) and President Bolsonaro (right) are fierce rivals for the presidency

Brazil is on tenterhooks as counting is under way in an election which will determine whether the world's fourth-largest democracy will continue to be led by the far-right incumbent or a left-wing former president.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva from the Workers' Party beat President Jair Bolsonaro from the Liberal Party by five percentage points in the first round, four weeks ago.

But the run-off could be close-fought.

The winner will be sworn in in January.

Polls opened at 08:00 local time (11:00 GMT) and closed at 17:00 (20:00).

Brazil's election chief, Alexandre de Moraes, ruled out extending voting after busses carrying voters were stopped by police at checkpoints.

Mr Moraes told reporters at a hastily-called news conference that, while some voters had been delayed on their way to the polls, none had been prevented from voting altogether.

He had earlier summoned the head of the highway police to the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) to question him about why buses full of voters had been stopped.

He also ordered the checks to be stopped in order to prevent any further voters from being delayed.

The two candidates for the presidency had cast their vote early in the day.

President Bolsonaro voted in Rio de Janeiro just minutes after the polls opened while Lula voted in his hometown of São Bernardo do Campo in São Paulo state.

Voting is electronic and results are expected within hours of the polls closing. The count can be followed live on the website of the electoral authority, external.

Voters from both sides of the political divide have endured an anxious four weeks since the first round.

Jair Bolsonaro won more votes than opinion polls had predicted but his main rival Lula fell short of the 50% of valid votes needed to win outright.

Five key facts about Lula

77 years old

Left-wing

Former metal worker

President from 2003-2010

Imprisoned in 2018 but conviction was later thrown out

While opinion polls are predicting a narrow win for Lula, many voters say they do not trust the polls after they underestimated the strength of support for President Bolsonaro.

With the final result up in the air, the president and his rival have been courting those Brazilians who cast their first-round ballots for one of the eight other candidates who did not make it into the run-off.

Ellen Monielle is a 23-year-old student and climate activist from the city of Natal in north-east Brazil - a Lula stronghold.

Even though many of her peers pressured her to vote for Lula, she backed Leonardo Péricles four weeks ago instead.

Ellen Monielle did not vote for Lula in the first round but she will in the second

Ms Monielle, whose mother is indigenous and whose father is black, says that she was excited to see a black man running for president and was thrilled that he chose a black woman as his running mate, adding: "I saw myself represented by them."

But when Mr Péricles got less than 0.1% of the votes, she decided to switch her allegiance to Lula.

Rather than an endorsement of the 77-year-old Workers' Party candidate, hers is a vote against President Bolsonaro.

"Bolsonaro represents everything that I'm not and that I don't believe in," she says, pointing out that the number of people going hungry in Brazil has risen under his presidency. One recent survey put it at more than 33m out of a population of about 217m.

Five key facts about Bolsonaro

67 years old

Far-right

Former army captain

Running for a second consecutive term

Has cast unsubstantiated doubts on the trustworthiness of Brazil's electronic voting system

"Yes, he's a male, old white guy but right now I'm telling people to vote for Lula on all my social media," Ms Monielle says.

There is no way I would vote for Lula

Gustavo Ramp is equally determined, but unlike Ms Monielle, he wants to prevent ex-President Lula - who led Brazil from January 2003 to December 2010 - from returning to office.

The 31-year-old company administrator is from Curitiba, a southern city which overwhelmingly voted for President Bolsonaro.

"Under Bolsonaro, the murder rate dropped, state companies which were making losses have been making profits and public security increased," Mr Ramp explains.

"Those are the kind of things that make me vote for Bolsonaro. There is no way I would vote for Lula."

Mr Ramp was only 11 years old when Lula was elected president for the first time in 2002. But he says he remembers how Lula's Workers' Party became engulfed in massive corruption scandals in the years which followed.

Like many Brazilians who oppose Lula, he says that it would be "humiliating" for the country if Lula - who served time in prison on corruption charges before his convictions were annulled - were to be re-elected.

Mr Ramp acknowledges that Mr Bolsonaro "is not the ideal candidate". "He has a very serious problem in that he talks too much," he says of the president's habit of making controversial, uncouth and homophobic statements.

Unlike many of Mr Bolsonaro's hardcore supporters, Mr Ramp describes himself as a liberal on social issues.

He thinks abortion should be legal up until 12 weeks of pregnancy and that same-sex couples should have the same legal rights as heterosexual couples - but he says he likes the president's tough approach to crime.

Eduardo Matos, a conservative sociologist, thinks more should be done to combat impunity

This is also something that appeals to Eduardo Matos, who is originally from Pernambuco state, in the north-east.

Mr Matos is a sociologist whose main area of study has been crime and violence. He is troubled by the fact that Brazil is one of the most violent countries in the world.

He says the laws in Brazil have been too lenient and that before Mr Bolsonaro came to power, a convicted murderer could spend as little as seven years behind bars thanks to a system which rewards good behaviour in jail.

Mr Matos wants to see tougher prison regimes to create a deterrent to crime and more investment in the police force, so that more criminals get caught and punished.

He thinks Mr Bolsonaro is the candidate who will deliver on those issues.

He also praises Mr Bolsonaro for loosening Brazil's gun laws. It allows Mr Matos to keep a weapon at his rural home and he says relatives of his have been able to avert home invasions because they were armed.

Bolsonaro is dangerous, he is a Latin copy of Trump

But looser gun laws is something which 50-year-old economist Evandro Barbiere from Rio is completely opposed to.

"Bolsonaro is dangerous, he is a Latin copy of [US President Donald] Trump," he says. "He's putting everyone at risk.

"When you're not a trained shooter and you have a gun, you put everyone around you at risk, including children and families."

Read more about gun culture: A US culture war raging in Brazil

Mr Barbiere says his heart is "totally with Lula" and that he will anxiously be watching the result come in on election night.

With what promises to be a nail-biting finish, he and people across Brazil will be glued to the official vote count.

Following a bruising and polarising campaign in which the two candidates and their teams lobbed accusations at each other ranging from corruption to cannibalism, there is an abiding sense of anxiety in both camps.

And many voters are weary of showing their allegiance on their way to the polls.

Cristina Mendes says she is having "a crisis of faith" due to the support of many evangelical Christians for Bolsonaro

Cristina Mendes, 43, is one of the evangelical voters whom both President Bolsonaro and Lula are trying hard to court.

Surveys suggest more than 60% of Brazil's evangelical Christians support Mr Bolsonaro but Ms Mendes is not one of them.

She may work for a missionary organisation but she says she has had "a crisis of faith" because of the support many evangelical churches have lent to Bolsonaro.

She has not attended church for years because she objects to politics being preached from the pulpit.

"Some pastors say Bolsonaro is God's chosen candidate," she says. "But I don't think God works like that, he doesn't choose candidates."

"Many evangelicals also say he represents Christian values, but I don't believe he does. I think God is about love and acceptance, not about imposing rules on those who think, worship or live differently.

"He speaks about indigenous people as if they were not humans, those are not Christian values, how can pastors support that?"

But aware that many of her neighbours and members of her church think differently, she will be keeping a low profile on election day.

"I won't wear a Lula badge and I will hurry home to watch the results from here," she says. "I'd rather not venture out."