Brazil Congress: ‘Sad to think we’ve come to this point’

- Published

In the hours after rioters tore through Brazil's most important democratic institutions, residents of an affluent Bolsonaro-voting area of Brasilia could still hear sirens in the distance.

Despite the sudden ferocity of the violence few were surprised.

Through apartment windows, you could see the glare of TV screens showing the news and violence at the presidential palace.

"It's a sad, sad day for Brazil. Unfortunately, I'm not surprised at all," said Victor, 28, a cafe kiosk worker.

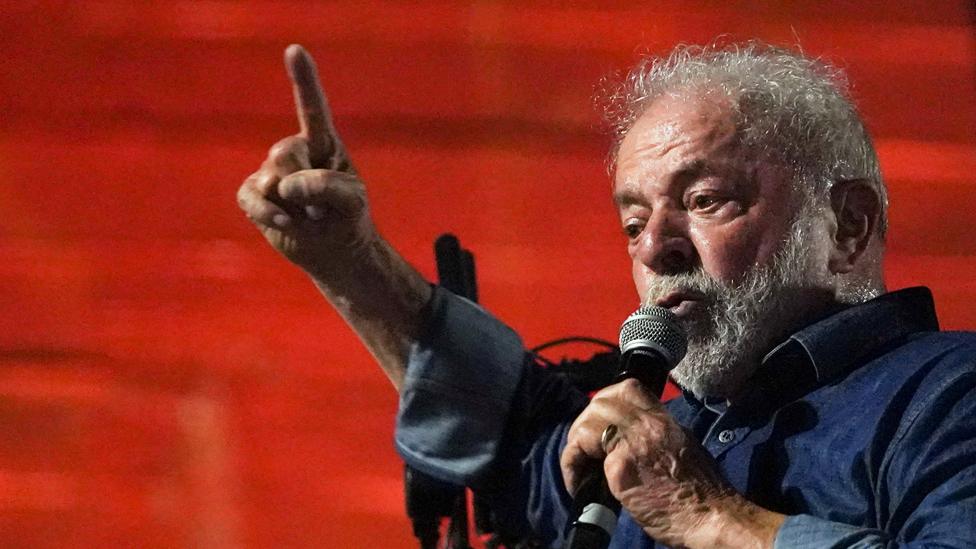

He said he had been expecting some sort of similar action before New Year's, when President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was inaugurated, and he described how more and more people - including his own brothers - had become sucked into "populist lies" and "divisive" politics.

When he heard the news in the afternoon, he said he was afraid, knowing that he was in a largely pro-Bolsonaro area.

Some of his regulars, Lula-voting neighbours in the apartments nearby, had even come down and offered him shelter in their apartments if the riots got closer.

"They said I could knock on their door!" he said but he had decided nervously to wait it out.

Outside the famous Our Lady of Fatima church just around the corner, a few people were praying, kneeling in the last pews even as the church custodian went to shut the lights off.

A woman outside the church told me she was struggling to get home because the subways had been suspended and the central bus station was also closed because it is in the blocked off central district.

She grew more emotional as she spoke about the violence.

"Brasilia is a non-political city, it's just the city that I live in and where I go about my day-to-day life. But at the same time, it's also a political city. And we live in these two parallel cities," she said, wishing to remain unnamed.

"So today it was sad to see Brasilia as a non-political city suffering aggressions because of its political side."

One of the men who had been praying told me it was a minority of people who wanted the riots and violence.

"But that's not what democracy is about. There will be winners and losers," said Oswald, 50.

"Winners will govern the country, losers have to accept, and the country will continue to grow and develop.

"I don't protest, I'm totally against what those people are doing. But my fear is to speak with someone who doesn't understand and is unwilling to understand others' views and I end up getting attacked. Because it ended up happening today."

Another young man I spoke to tonight in the neighbourhood identified as a Bolsonaro supporter but shook his head at the violence.

"I voted for Bolsonaro, but I don't agree with what they're doing," Daniel Lacerda, 21, told me.

He told me about the frustration people felt with the problems of corruption in Brazilian politics - and the rampant poverty in so many parts of the country.

"It's sad to think that we've come to this point where people think the only solution is violence. That's really sad. I don't feel happy in any way. I think there are other ways to solve this."

Watch: Video shows Brazil Supreme Court break-in

Related topics

- Published9 January 2023

- Published31 October 2022

- Published26 December 2022