Cuban exodus: 'I just don't see a future here for me'

- Published

Deivid (right) dreams of playing professional baseball in the US

An accomplished pitcher and first baseman from Havana, 12-year-old Deivid Acosta's eyes light up when he talks of potentially playing competitive baseball in the United States.

He's now tantalisingly close. Thanks to an agreement reached a few years ago, Cuban children will compete for the first time in the Little League World Series in Pennsylvania in August.

Deivid is confident of making the cut.

Batting in Havana's morning heat, the two-times Cuban homerun leader in his age category delivered an assured performance in front of an important visitor: the president of US Little League, Stephen Keener.

"The New York Yankees, always," Deivid says with a smile when asked where he sees himself playing one day.

Yet unlike top baseball prospects from the Dominican Republic or Puerto Rico, his route to the Major League in the US is far from assured.

Like most Cubans, Deivid has grown up under the twin complexities of the US trade embargo and communist rule. A tangled bureaucratic combination of the two has long restricted opportunities for young players like Deivid and his teammates to travel or train abroad.

Mr Keener tacitly acknowledged the embargo's impact on Cuba's youth teams by promising to supply bats, gloves, balls and one day "build a Little League field in Cuba".

But scarcity is simply a part of the players' young lives, often of more important things than baseball gloves: eggs, bread, soap, medicines. The list of shortages changes but never ends.

On 7 February 1962, President John F Kennedy extended the embargo to include virtually every export. It's now the longest-running economic sanction in the world.

Most Cuban farmers lack access to modern equipment

Under the embargo, cargo ships cannot dock in US ports for 180 days if they've previously docked in Cuba, deterring international freight companies from shipping to the island. White goods, car parts or medical equipment with US-made components are also banned from sale to Cuba.

In 2018, the United Nations called the embargo on Cuba "unjust" and said it had cost the island's economy some $130bn (£108bn) over the past six decades.

That the embargo is harsh is rarely contested by Washington. Indeed, it is intended to be.

But it's also the source of an eternal blame game: Is the US sanction the cause of Cuba's dire economic problems and scarcity, or is it the perfect excuse behind which the Cuban state hides its own shortcomings and failings?

For every die-hard revolutionary who insists the embargo is solely to blame for Cuba's ills, there's an equally committed opponent pointing the finger squarely at Cuban communism.

"One way to look at it is that the two things have interacted with each other over six decades to produce a catastrophe, an economic and social catastrophe," says Ricardo Torres, a Cuban economist and research fellow at American University in Washington DC.

"Clearly, the embargo puts additional strain on Cuba's development. But I think currently the main constraint is the system, the country's economic model."

Whatever one's position on that endless debate, the dire circumstances have undeniably sparked an exodus, the like of which the island hasn't seen in years.

Miriela Cruz is among those desperate to leave Cuba soon. A cancer patient and mother of two, she spoke to the BBC in August 2021 after her son was jailed in a dragnet of arrests following nationwide anti-government demonstrations the month before. Street protests are banned in Cuba and the government clamps down on all forms of dissent.

Miriela is struggling for medicines to treat her lung cancer

Drawn and exhausted from her chemotherapy treatment, she was physically and emotionally drained.

Speaking out about her son's detention put Miriela into direct conflict with the authorities. Now deemed a "counter-revolutionary", she's found life even tougher and says she's subject to constant harassment from Cuba's state security.

"I honestly want to leave this country more than anything. With my health issues, there aren't any of the medicines I need, not even painkillers. There's no food - I have days where I simply don't eat anything. I just don't see a future here for me."

The state-run centrally controlled model has failed to deliver for people like Miriela, argues economist Ricardo Torres, while the embargo has allowed the Cuban authorities to "look the other way in terms of things which need to be addressed".

Whether relaxing controls on the private sector, reform of the dysfunctional banking system or easing the military's vice-like grip over the import-export business, the Cuban government "still has a lot of agency when it comes to transforming the reality of the country," he adds.

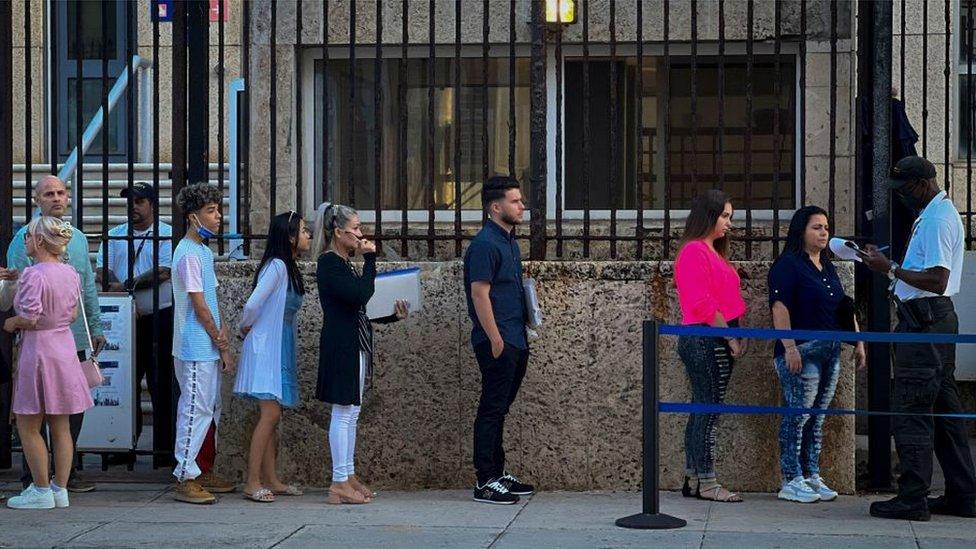

With so many Cubans arriving on US shores, the Biden administration has now introduced a new humanitarian visa plan. Every day, long queues of people clutching their paperwork line up outside the US embassy in Havana.

Every day people queue outside the US embassy in Havana for visa appointments

With most of Cuba's arable land cultivated by oxen-and-plough or Soviet-era tractors, a green shoot of improved ties came from Joe Biden's home state, Delaware. A visiting agricultural delegation spoke of their hopes for a more normal trade relationship, insisting "the potential for collaboration today is greater than ever before".

Yet Cubans have heard such talk before - particularly during the Obama-era thaw between Washington and Havana - and are fully aware that only the US Congress can lift the embargo. Given the deep divisions in the House of Representatives, that appears a very distant prospect.

Meanwhile, Miriela's health remains so precarious, she's contemplating the ultimate risk: crossing the Florida Straits in a boat.

"Whatever I have left to live, whether two years, three days, a month, I want to live it with dignity," she says. "Here there's no tomorrow, no hope."

Related topics

- Published24 July 2022

- Published10 January 2023