Brazil school attacks: 'I always look for places to hide'

- Published

Yanne Cezário survived a shooting at her high school

"It still affects me. To this day, whenever I go out, I catch myself looking for places to hide and for escape routes, in case something happens."

Yanne Cezário is a survivor of a 2019 school shooting in the Brazilian city of Suzano.

The assault on the Raul Brasil school, in which two young men stormed the building, killing eight people and injuring 11 more, was one of the worst ever to have taken place in Brazil.

The trauma from that day has stayed with Yanne ever since.

She was 17 years old at the time, in her final year. Yanne remembers running from the killer and, as she turned around, seeing him shoot one of her friends dead. She had to hide under bodies in her struggle to survive and was stepped on by other pupils who were desperately trying to escape.

"When I finally got out, I had blood all over my clothes - mine and other people's."

The reality of what had happened only hit her the day after, she says, when she came home from the collective funeral organised by local authorities.

Five teenagers were among those killed in the attack on the school in Suzano, near São Paulo, in 2019

"I lay beside my mother and started screaming from the top of my lungs, shouting that I wanted my friends back, that I didn't understand what happened."

Since then, Yanne has been taking antidepressants and doing therapy. Her anxiety attacks are not as bad as they were at the beginning, when she used to faint in crowded places. But she still feels shortness of breath at times.

Some of the effects, however, are irreversible. Now 21 years old, the tragedy has made Yanne choose distance learning instead of going to a university. For years she had wanted to become a teacher, but did not feel ready to go back to a class full of people.

She thought she would be ready by now, as the time for her first mandatory placement in a school approaches. But a recent spate of further school attacks in Brazil has worried her.

Read more about recent attacks:

"The day I got the email about the internship I remember going to my room and thinking to myself: 'I can't believe this is all happening again'," she says. "But this is what I chose, so I'm going through with it."

Much to the horror of families and Brazil's government, these attacks, which used to be one-off events, are becoming more common across the country. Over the last two decades there have been 22 attacks in schools carried out by former students, with 13 of these taking place in the last two years, according to data gathered by the Moral Education Study and Research Group (Gepem) at Campinas State University (Unicamp).

Rhyllary Barbosa de Sousa, another survivor from the Suzano school shooting, was 15 when the attack happened. She has experienced severe depression ever since and even attempted suicide.

"To be honest, the only good thing I still have from that time is my Jiu-Jitsu practice," she says.

Rhyllary Barbosa was 15 when her school was attacked

She had been practicing Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu since her early teens and, she says, it was these martial arts skills which helped her to avoid being knocked down by the killer during the attack and to open one of the school's doors so that other students could escape. She still attends Jiu-Jitsu classes every weekday.

The most recent series of attacks - two occurring in the first three months of 2023 - has made Rhyllary reflect on why these assaults are increasing and what more could be done to prevent them from happening in the first place.

"They [the parents] need to comfort their kids, to create a safe space for them to talk about their problems," she says.

She also feels there is a need for society to start paying more attention to what happens on the internet. Rhyllary constantly receives threats online from teenagers who say they are inspired by the killers who invaded her school. She says that social media is playing a role in radicalising young people in Brazil.

This is backed up by the research done by expert César Nunes. He is part of the Gepem group at Campinas State University, that studies these attacks, and has been monitoring social media platforms used to plan them.

He says right-wing extremist content that years ago was restricted to the deep web is now widely available on social media. That has made it easier for groups promoting Nazi, white supremacist and misogynistic content to co-opt teenagers who feel isolated or rejected at school.

"They teach them how to use weapons, how to be one of the greats in their 'Hall of Fame' - they have these kinds of things. It's terrible."

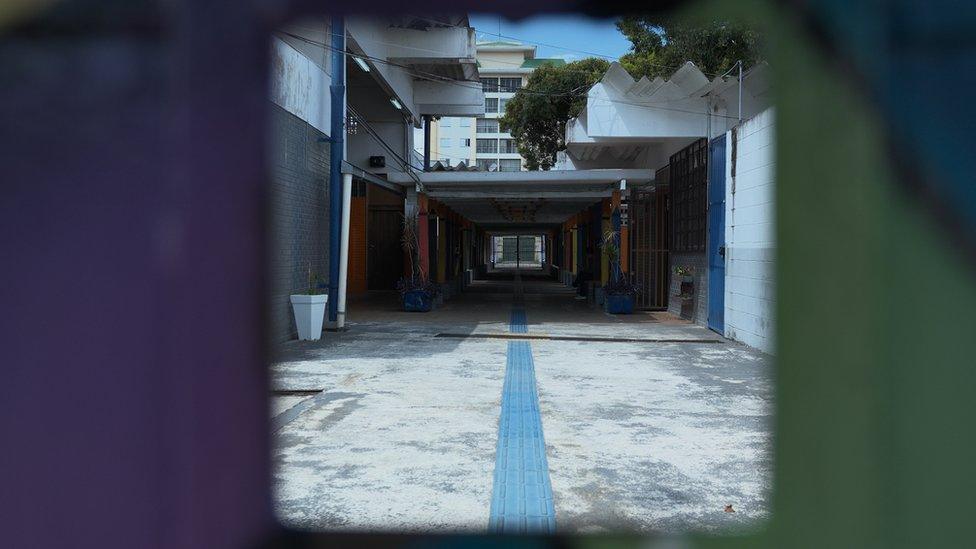

Schools in Suzano now keep their gates closed at all times

But Mr Nunes believes the internet is just one factor.

He says that the Covid-19 pandemic, which forced many teenagers to spend more time online and helped weaken their social ties with family and friends, has played a role.

A divisive presidential election campaign which saw left-winger Inácio Lula da Silva challenge the far-right incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro, further polarised Brazil and fomented violent political rhetoric, which in turn created an environment that negatively impacts young people, he argues.

In October 2022, Lula won the election by the narrowest margin in Brazil's recent history.

Lula has been in office since January, but some of the policies brought in during Mr Bolsonaro's time in office - such as the loosening of gun restrictions - are having a lasting effect, according to an extensive report prepared by a group of specialists during the government transition.

The report links the surge in school violence to the growth of far-right extremism in Brazil over recent years and the spread of hate speech online.

It also lists the attempts by the Brazilian Congress to ban subjects such as diversity and racism from being discussed in classrooms as one of the factors negatively impacting students.

The response to the attacks varies throughout the country. Each of Brazil's 5,572 municipalities controls its own primary education, while secondary schools are run by state-level governments.

Some school areas have focused on beefing up security, especially after a recent wave of online threats in the build-up to 20 April, the anniversary of the 1999 Columbine shooting in the United States.

Yanne - the survivor of the Suzano school shooting four years ago - had never heard of Columbine before her own school was attacked by two teenage assailants who had told their friends that they wanted to "copy" the US massacre which left 12 children and a teacher dead.

Since then, school authorities have been on heightened alert around the time of the Columbine anniversary.

Municipal schools in Suzano are now patrolled by the police

Some Brazilian schools try to tackle the problem before it develops, hiring psychologists to tackle bullying and hostility among students.

At the federal level, the ministry of justice has launched a hotline so authorities can get information about school violence, and has ordered social media platforms to take down profiles that encourage school attacks.

Almost 800 were removed before 18 April this year, ministry of justice figures suggest.

The city of Suzano is trying a dual approach. On the one hand, local authorities have introduced tougher security measures. The 74 municipal schools in the city are now monitored by more than 1,000 closed-circuit security cameras and regularly patrolled by armed police with dogs.

The city also runs a programme training teachers to identify and deal with bullying and violent behaviour among students, which it hopes will prevent troubled children from becoming attackers.

Teachers have been trained to identify bullying and violent behaviour in students

In Mr Nunes's view, working inside schools to create a welcoming environment and investing in conflict resolution is key to efforts to tackle the problem.

"It's a long term solution," he says. "We have to learn how to share space with others, how to compromise. If we don't do it in our schools, we won't be able to do it as a society."

He says boosting security should be restricted to more extreme cases, where there is a specific threat. "When you look at what's happening to the United States, they're investing heavily in security, and still they have more school attacks than any other place."

Adriana, a nurse who lives in the city of Vitória, in south-east Brazil, is the mother of a teenager who in August 2022 attacked the school he once attended.

The then 18-year-old stormed the building carrying a crossbow and a knife, but fortunately was stopped by school employees before he could carry out his plan.

Adriana says there were some warning signs that something was off - and has a stark warning for others.

"My advice to parents is: Pay attention to your children, be aware of their online activities, who they're talking with.

"The radicalisation process can start at a very young age. It's better to be safe than sorry."

- Published5 April 2023

- Published15 April 2023

- Published9 January 2023