Redonda: Tiny Caribbean island’s transformation to wildlife haven

- Published

Seabirds now flock to the newly verdant isle

The incredible eco-restoration of one tiny Caribbean island - transformed from desolate rock to verdant wildlife haven in just a few years - has captured the imagination of environmentalists worldwide.

Now the tenacious Antiguans and Barbudans who led the metamorphosis of the country's little known third isle of Redonda are celebrating another impressive feat.

The mile-long spot has been officially designated a protected area by the country's government, ensuring its status as a pivotal nesting site for migrating birds and a home for species found nowhere else on Earth is preserved for posterity.

The Redonda Ecosystem Reserve, which also encompasses surrounding seagrass meadows and a coral reef, spans a colossal 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres).

Its sheer size means the country has already met its "30x30" target, a global goal to protect 30% of the planet for nature by 2030.

Today, Redonda is bursting with biodiversity including dozens of threatened species, globally important seabird colonies, and endemic lizards.

The number of ground dragons rebounded as the environment recovered

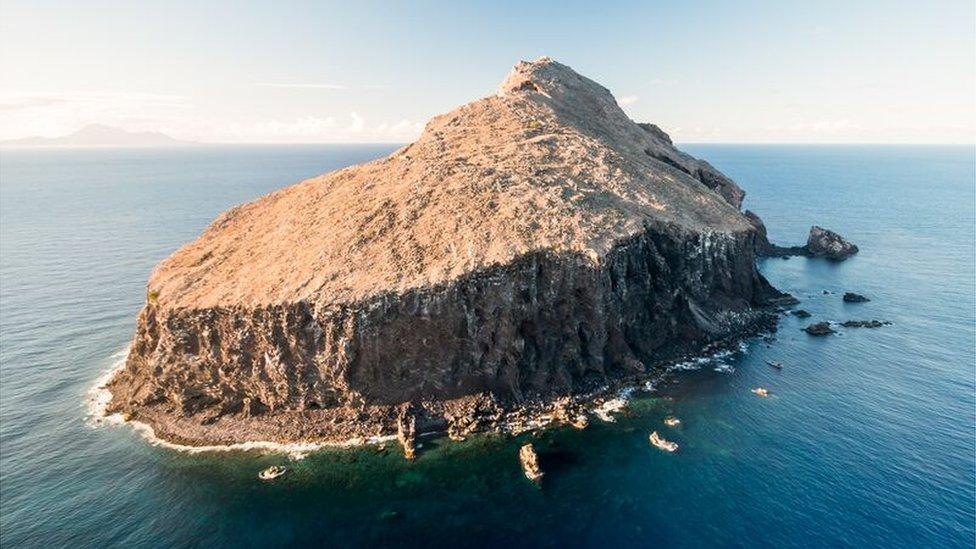

It did not always look like this. Invasive black rats that preyed on reptiles and ate birds' eggs, along with goats introduced by early colonists that devastated Redonda's vegetation, had left the island looking like a barren moonscape.

An ambitious project launched in 2016 to relocate the goats and eradicate the rats saw the greenery spring back to life, bringing with it an exponential rise in native species.

The work was piloted by local NGO, the Environmental Awareness Group (EAG), in sync with the government and overseas partners including Fauna and Flora International (FFI).

The EAG's executive director Arica Hill describes the new protected status as a "huge win for Antiguans and Barbudans".

"This is the largest marine protected area in the Eastern Caribbean; it showcases the amazing work that conservationists and environmentalists can do right at home," she tells the BBC. "What is even more significant is that the government has trusted us to legally manage it too."

Magnificent frigatebirds are among those nesting on the island

The group is already carrying out feasibility studies in the hope of reintroducing species found on Redonda many years ago, such as the burrowing owl, a small sandy-coloured bird that nests underground.

The EAG is also setting up a robust governance system to ensure the island remains free of invasive critters. That includes surveillance cameras to look out for errant rats and monitoring local fishing activities which must adhere to strict guidelines.

FFI's Jenny Daltry says Caribbean islands face the highest extinction rates in modern history, meaning the restoration and protection of areas like Redonda is "critical".

There is a wealth of seabirds on Redonda's cliffs

Since the efforts began, 15 species of land birds have returned to the island, while numbers of endemic lizards like the critically endangered Redonda ground dragon have soared.

Local residents who once dubbed Redonda "the rock" are now its most vehement guardians, says the EAG's Shanna Challenger.

Before its restoration, locals called Redonda a "rock", and it is easy to see why

"Our little sister island that many people never see has been able to invoke such national pride," she smiles.

"To me as an Antiguan and Barbudan, this work has been monumental. We are forever written into the fabric of Redonda's history; I'm so proud to have been instrumental in this and can't wait to see what Redonda's legacy will be moving forward."

For small developing islands that exist on the frontier of climate change, Redonda's success represents a rare bright spark amid a glut of gloomy environmental headlines.

Now, the island is much greener

"Reaching our '30x30' target tells the rest of the world that this is possible. Even though we don't put out the most emissions, we are among the most impacted and we are still the ones meeting our target early," Shanna continues.

"We are putting our money where our mouth is. I hope this is an inspiration to other countries that if little Antigua and Barbuda can do it, so can you."

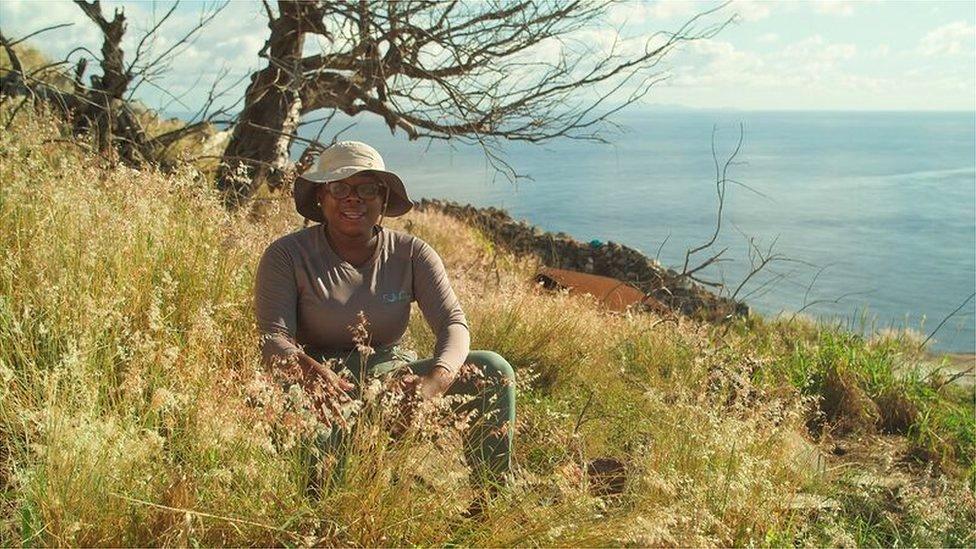

For Johnella Bradshaw, the reserve's coordinator, the accomplishments are more personal still.

Johnella Bradshaw is proud of what has been achieved on Redonda

"Growing up, going through school and college, a career in the environmental field was unheard of. The emphasis was on being a doctor, dentist or lawyer," she says.

"When you think about conservation, you think about things happening in America or Europe, not a little island in the Caribbean.

"Now we are at the forefront of international conservation we can change that narrative, and show younger generations that people who look like me can do this."

Johnella is eager to prove that the protected status won't just exist "on paper" but "in reality too".

The waters off the island are also teeming with life

Like her compatriots, she's all too aware of the unprecedented climactic conditions facing the country. Six years ago, Barbuda was devastated by Hurricane Irma and warming seas continue to pose an existential threat to islands across the region.

"You hear about climate change, rising temperatures and stronger storms but we are feeling it. This summer has been awful, it's so hot," Johnella adds. "But if we all play our part, together we can make a difference."